|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9474-A - (p) 1965

|

|

| 1 CD -

2564-69853-2 - (c) 207 |

|

GOLDBERG

VARIATIONEN 1740

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Aria

mit 30 Variationen (Klavierübung Teil

IV), BWV 988 |

|

47' 45" |

|

|

- Aria

|

2' 24" |

|

A1 |

|

- Variatio

1, a 1 Clav.

|

1' 31" |

|

A2 |

|

- Variatio 2, a 1 Clav.

|

1' 00" |

|

A3 |

|

- Variatio

3, a 1 Clav. - Canone

all'Unisono

|

1' 03" |

|

A4 |

|

- Variatio

4, a 1 Clav. |

0' 35" |

|

A5 |

|

- Variatio 5, a 1 ovvero 2 Clav.

|

1' 02" |

|

A6 |

|

- Variatio 6, a 1 Clav. - Canone

alla Seconda

|

0' 57" |

|

A7 |

|

- Variatio

7, a 1 ovvero Clav. - Al

tempo di Giga

|

1'

03"

|

|

A8 |

|

- Variatio

8, a 2 Clav. |

1' 22" |

|

A9 |

|

- Variatio

9, a 1 Clav. - Canone alla

Terza

|

1' 05" |

|

A10 |

|

- Variatio

10, a 1 Clav. - Fughetta

|

0' 54" |

|

A11 |

|

- Variatio

11, a 2 Clav. |

1' 26" |

|

A12 |

|

- Variatio

12, Canone alla Quarta |

1' 50" |

|

A13 |

|

- Variatio 13, a 2 Clav.

|

2' 52" |

|

A14 |

|

- Variatio 14, a 2 Clav.

|

1' 20" |

|

A15 |

|

- Variatio 15, a 1 Clav. - Canone

alla Quinta,

Andante

|

2' 40" |

|

A16 |

|

- Variatio

16, a 1 Clav. - Ouverture

|

1' 32" |

|

B1 |

|

- Variatio 17, a 2 Clav.

|

1' 04" |

|

B2 |

|

- Variatio

18, a 1 Clav. - Canone alla

Sesta

|

0' 47" |

|

B3 |

|

- Variatio

19, a 1 Clav. |

0' 55" |

|

B4 |

|

- Variatio 20, a 2 Clav.

|

1' 14" |

|

B5 |

|

- Variatio

21, Canone alla Settima |

2' 07" |

|

B6 |

|

- Variatio

22, a 1 Clav. - Alla breve

|

0' 48" |

|

B7 |

|

- Variatio

23, a 2 Clav. |

1' 22" |

|

B8 |

|

- Variatio

24, a 1 Clav. - Canone

all'Ottava

|

1' 59" |

|

B9 |

|

- Variatio

25, a 2 Clav. - Adagio

|

4' 22" |

|

B10 |

|

- Variatio

26, a 2 Clav. |

1' 10" |

|

B11 |

|

- Variatio

27, a 2 Clav. - Canone alla

Nona

|

1' 04" |

|

B12 |

|

- Variatio

28, a 2 Clav. |

1' 30" |

|

B13 |

|

- Variatio

29, a 1 ovvero 2 Clav. |

1' 10" |

|

B14 |

|

- Variatio

30, a 1 Clav. - Quodlibet

|

1' 08" |

|

B15 |

|

- Aria da

capo

|

2' 35" |

|

B16 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gustav LEONHARDT,

Cembalo (Kielflügel) Martin

Skowroneck, Bremen 1962, kopiert

bach einem Kielflügel von J. D.

Dulcken, Antwerpen 1745 |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Hervormde Kerk in

Bennebroek (Holland) - 28/29

Aprile 1965

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9474-A | 1 LP -

durata 47' 45" | (p) 1965 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Warner Classics

| LC 04281 | 2564-69853-2 |

1 CD - durata 47' 45" | (c)

2007 | ADD

|

|

|

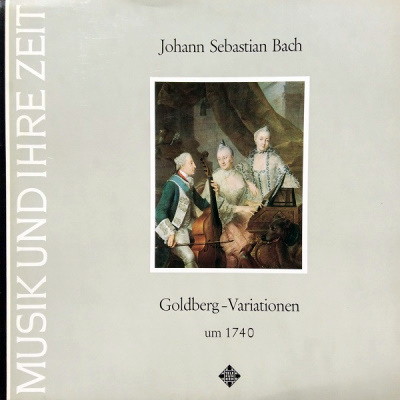

Cover Art

|

|

"Kurfürst Max III.

Joseph mit seiner Gemahlin und

seiner Schwester musizierend".

Gemälde von Johann Nikolaus Grooth

(Original im Schloß Nymphenburg).

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

The Goldberg

Variations are not only the

most extensive variation

composition of the baroque

age but also the most

complicated and manifold.

Bach has taken the “Aria“ on

which they are based from

his own Music Book for Anna

Magdalena of 1725; it is not

certain whether he himself

wrote the melody. It is in

the form of a sensitive

little sarabande in G major

with a richly embellished

upper part. Its metric and

harmonic structure is,

however, very simple: two

sections of sixteen bars,

divided further into

eight-bar groups, each

consisting of four two-bar

sarabande phrases. Almost

every bar (the exceptions

being the final bars 16 and

32) is dominated by the

characteristic sarabande

rhythm, the whole being

based on a simple cadential

plan that leads, in calm

progressions corresponding

exactly to the metrical

divisions, from the tonic

through the domi- nant, the

relative minor and the

subdominant back to the

tonic. It is this cadential

plan, together with its

supporting bass line, that

forms the basis of the

variations; the sara- bande

melody in the upper part is

generally only alluded to,

not properly varied. Thus

the Goldberg Variations

belong to the tradition of

“variations on a ground

bass“, of the chaconne and

the passacaglia. But at the

same time they fill this

rigid form to its very

limits, not only with a

magnificent unfolding of all

its inherent possibilities

but furthermore with the sum

of nearly all the forms and

movement types of the

instrumental music of the

age. Throughout the work we

find three consecutive

variations always formed

into a group, of which the

first and second pieces

display forms, types of

composition and aspects of

harpsichord technique, while

the third in each case is

formed as a strict canon.

These canons are arranged in

themselves according to _

the intervals at which the

canonic entries occur, from

the unison to the ninth,

their intensity of

expression growing and

changing with the intervals

from the playful and relaxed

to the brooding and earnest.

Finally, the number of

variations - thirty -

corresponds exactly to the

number of bars in the aria

minus the cadence bars . 16

and 32; the middle of the

cycle is marked by Variation

15 (canon at the fifth) as

the first piece in G minor

and Variation 16 as a

resplendent French overture

that opens the second part.

To conclude the cycle the

thir- tieth variation, the

famous Quodlibet, gives us a

Kumoristic “interpretation“

of the entire work in

retrospect by means of two

folk-song quotations. The

chaconne bass is played

almost without

embellishment, the upper

voices playing in skillful

imitation and combination

the song “Ich bin so lang

nicht bei dir gwest“ (I have

not been with you for such a

long time) - referring to

the Aria melody that really

belongs to this bass.’ They

then give the reason in the

other song: “Kraut und

Rüben“ (Cabbage and turnips)

- meaning the variations -

“haben micht vertrieben“

(have driven me away). As a

logical consequence, the

Aria is repeated after this

contrite declaration,

restoring the original order

and concluding and rounding

off the cycle to everybody’s

satisfaction.

We thus find the following

overall plan: The Goldberg

Variations are not only the

most extensive variation

composition of the baroque

age but also the most

complicated and manifold.

Bach has taken the “Aria“ on

which they are based from

his own Music Book for Anna

Magdalena of 1725; it is not

certain whether he himself

wrote the melody. It is in

the form of a sensitive

little sarabande in G major

with a richly embellished

upper part. Its metric and

harmonic structure is,

however, very simple: two

sections of sixteen bars,

divided further into

eight-bar groups, each

consisting of four two-bar

sarabande phrases. Almost

every bar (the exceptions

being the final bars 16 and

32) is dominated by the

characteristic sarabande

rhythm, the whole being

based on a simple cadential

plan that leads, in calm

progressions corresponding

exactly to the metrical

divisions, from the tonic

through the domi- nant, the

relative minor and the

subdominant back to the

tonic. It is this cadential

plan, together with its

supporting bass line, that

forms the basis of the

variations; the sara- bande

melody in the upper part is

generally only alluded to,

not properly varied. Thus

the Goldberg Variations

belong to the tradition of

“variations on a ground

bass“, of the chaconne and

the passacaglia. But at the

same time they fill this

rigid form to its very

limits, not only with a

magnificent unfolding of all

its inherent possibilities

but furthermore with the sum

of nearly all the forms and

movement types of the

instrumental music of the

age. Throughout the work we

find three consecutive

variations always formed

into a group, of which the

first and second pieces

display forms, types of

composition and aspects of

harpsichord technique, while

the third in each case is

formed as a strict canon.

These canons are arranged in

themselves according to _

the intervals at which the

canonic entries occur, from

the unison to the ninth,

their intensity of

expression growing and

changing with the intervals

from the playful and relaxed

to the brooding and earnest.

Finally, the number of

variations - thirty -

corresponds exactly to the

number of bars in the aria

minus the cadence bars . 16

and 32; the middle of the

cycle is marked by Variation

15 (canon at the fifth) as

the first piece in G minor

and Variation 16 as a

resplendent French overture

that opens the second part.

To conclude the cycle the

thir- tieth variation, the

famous Quodlibet, gives us a

Kumoristic “interpretation“

of the entire work in

retrospect by means of two

folk-song quotations. The

chaconne bass is played

almost without

embellishment, the upper

voices playing in skillful

imitation and combination

the song “Ich bin so lang

nicht bei dir gwest“ (I have

not been with you for such a

long time) - referring to

the Aria melody that really

belongs to this bass.’ They

then give the reason in the

other song: “Kraut und

Rüben“ (Cabbage and turnips)

- meaning the variations -

“haben micht vertrieben“

(have driven me away). As a

logical consequence, the

Aria is repeated after this

contrite declaration,

restoring the original order

and concluding and rounding

off the cycle to everybody’s

satisfaction.

We thus find the following

overall plan:

| Aria |

|

|

Variatio 16 |

French

Overture

|

Variatio 1

|

Two-part

Invention, quasi

Corrente

|

|

Variatio 17 |

Two-part

concerto movement,

similar to

Variatio 14

|

Variatio 2

|

Three-part

Sinfonia

|

|

Variatio 18 |

Two-part

Canon at the

sixth, alla breve,

in stretto with

free bass

|

Variatio 3

|

Two-part

Canon at the

unison with free

bass

|

|

Variatio 19 |

Three-part

Minuet

|

Variatio 4

|

Four-part

imitatory, quasi

Passepied

|

|

Variatio 20 |

Two-part

concerto movement

for two manuals

with crosing of

the hands,

virtuoso keyboard

figuration and

off-beat

semiquavers

|

Variatio 5

|

Two-part

Invention for one

or two manuals

with crossing of

the hands

|

|

Variatio 21 |

Two-part

Canon at the

seventh with free

chromatic bass, in

G minor

|

Variatio 6

|

Two-part

Canon at the

second with free

bass

|

|

Variatio 22 |

Four-part

alla breve,

three-part Fugato

over a free bass

in the style of a

ricercar

|

Variatio 7

|

Two-part

Gigue

|

|

Variatio 23 |

Two-part

concerto movement

for two manuals

with virtuoso

keyboard

figuration, runs,

off-beat chords

and crossing of

the hands

|

Variatio 8

|

Two-part

Invention for two

manuals with

crossing of the

hands

|

|

Variatio 24 |

Two-part

Canon at the

octave over a free

bass, quasi Gigue

|

Variatio 9

|

Two-part

Canon at the third

with free bass

|

|

Variatio 25 |

aria

descant movement

with two-part

chromatic

foundation in G

minor

|

| Variatio 10 |

Four-part

Fughette

|

|

Variatio 26 |

Chordal

Sarabande in 3/4

time with

"disembellished"

aria melody in the

upper part and

superimposed

flowing 18/16

motion, both

alternately in the

right and the left

hand, on two

manuals

|

| Variatio 11 |

Two-part

Gigue for two

manuals with

crossing of the

hands

|

|

Variatio 27 |

Two-part

Canon at the ninth

without free bass

|

| Variatio 12 |

Two-part

Canon at the

fourth in contrary

motion with free

bass

|

|

Variatio 28 |

Virtuoso

concerto movement

in free writing

"Etude" in

written-out trills

and double trills

|

| Variatio 13 |

Aria

descant movment

with two-part

foundation

|

|

Variatio 29 |

The same,

"Etude" in

off-beat chords

|

| Variatio 14 |

Two-part

concerto movement

for two manuals

with crossing of

the hands and

virtuoso keyboard

figuration

|

|

Variatio 30 |

Three-part

Quodlibet over a

free bass

|

| Variatio 15 |

Two-part

Canon at the fifth

in contrary motion

with free bass, in

G minor

|

|

Aria

repeated

|

|

In

this magnificent musical

structure we find reflected

the inexhaustible and

unfathomable variety of a

real musical cosmos, similar

to the order of this world

and its relation to an

unchangeable and

ever-present centre - here

represented by the chaconne

bass. This is true not only

in the obvious musical

sense, but at the same time

as a profound symbolism

hardly to be understood

except in theological terms,

which seems to elevate this

“commissioned“ work into

nothing less than an image

of the universal order.

Ludwig

Finscher

Martin

Skowroneck writes

about the harpsichord

he built

ın 1962/63 in the

style of J. D.

Dulcken:

Johann Daniel

Dulcken was the son of

the instrument maker

Anton Dülcken, who had

emigrated

from Hessen to Brussels.

J. D. Dulcken set up his

workshop about 1740 in

Antwerp and moved

in 1764 (after his

father’s death) to

Brussels. Twelve to

fifteen of his

harpsichords, dating

from

between 1741 and 1769,

have been preserved,

and, according to

Lüttgendorf, some lutes.

(Not

all the instruments

attributed to him can be

said with certainty to

have come from his

workshop,

and it is possible that

many more, not generally

known, may exist in

private ownership.)

Charles

Burney in his travel

diary of 1772, in which

he writes about the

Antwerp harpsichord

builders,

calls J. D. Dulcken the

best harpsichord maker

after the Ruckers

family, and mentions

Joannes

Bull as a pupil of his

who had done very fine

work. Certainly he

misses the pedals for

changing

registers common in

England at that time,

and the swell, and

remarks that the

instruments outwardly

are painted without

decoration, a feature of

all Netherlands and also

of many German

claviers. Dulcken in his

instruments adheres to

the tradition of the

Antwerp harpsichord

makers, above all the

Ruckers family: the

materials employed are

similar, and the outward

appearance

of the painted case and

of the soundboard

painted with flowers is

that which had been

common

in Antwerp for more than

a century. The carefully

thought out interior

construction is a

logical

development from the

Ruckers instruments to

an impressive larger

model, with a

five-octave

compass and a length of

2.60 metres. It permits

a light and therefore

exceptionally stable

method

of construction, by

which the whole case and

not merely the

soundboard contributes

to the tone.

This

replica harpsichord is

no exact copy but new

construction based on

examinations of

two Dulcken. instruments

in Washington. and

Vienna, preserved from

the year 1745. Moreover,

for purposes of

comparison instruments

of other contemporaries

were referred to,

particularly

of his pupil Joannes

Bull. In the new

manufacture, the

framework and bulk were

treated with

the freedom usual in

early harpsichord

making. The tolerances,

which in several extant

originals

of one and the same

master are identical,

ensure a uniform total

conception and a close

kinship

of tone as well as the

individuality of each

single instrument. A

copy, exact to the

millimetre, of

a single surviving

original — possibly

repeated several times —

runs counter to the old

tradition

and can falsify the

picture, in that

isolated particular

requirements (e.g.

slightly harder or

softer’

wood or other special

wishes of the customer)

are thoughtlessly

reproduced. What is

more, by

exact copying it is as

little possible to

attain the musical

qualities of a

harpsichord as of a

Stradivarius. On the

other hand, measurements

must not be so much

altered, or new

construction

elements introduced,

that one can no longer

speak of an instrument

“in the style of ...”

and

expect musical results

similar to the original

and specially suited for

the performance of

historical

music. Hence it was

accepted that all the

advances of modern piano

and harpsichord making

should

be forgone: material,

construction and the

wooden mechanical parts

without regulating

screws

are in accordance with

the original design.

This harpsichord is

individually made by

hand

in every part. That was

the practice in early

harpsichord making, as

today it is still common

usage

in the making of

stringed instruments. At

the start of the 19th

century a member of the

Dulcken

family (Johann Ludwig,

born 1761 in Amsterdam,

until 1835 “Court piano

maker in Munich”)

was still refusing to

extend his workshop, on

the grounds that “the

completing of an

instrument

must remain in one pair

of hands’.

The disposition is that

of almost all the

two-manual harpsichords

of the late 17th and the

18th

centuries: Lower manual,

8’, 4’: Upper manual 8’:

manual coupler. On the

upper manual, the nasal

“lutestop” of English

instruments (common with

Dulcken), a row of jacks

close to the

plank-bridge (nut)

passing through the

wrest-plank, which acts

as an alternative row of

jacks on

the same 8’ strings.

|

|

|

|