|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9465-B - (p) 1965

|

|

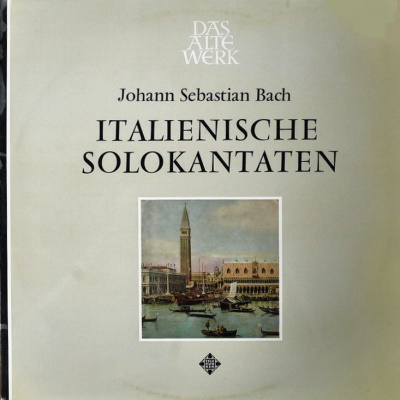

| 1 LP -

SAWT 9465-B - (p) 1965 |

|

| 11 CDs -

3984-25710-2 - (c) 2000 |

|

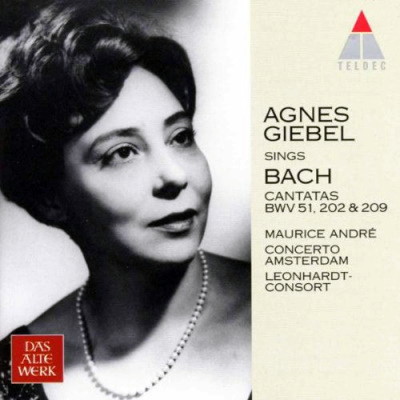

| 1 CD -

3984-21711-2 - (c) 1998 |

|

ITALIENISCHE

SOLOKANTATEN

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Kantate

"Non sa che sia dolore", BWV 209 -

Leipzig zwischen 1730 und 1734 |

|

17' 23" |

|

|

Solokanatate

für Sopran · Instrumente: Flauto

traverso, Violine I und II, Viola und

Basso continuo |

|

|

A1 |

|

- Sinfonia

|

7' 32" |

|

A2 |

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "Non sa che sia

dolore"

|

0' 46" |

|

A3 |

|

-

Aria (Sopran): "Partipur e con dolore"

|

8' 35" |

|

A4 |

|

-

Recitativo (Sopran): "Tuo saver" |

0' 30" |

|

A5 |

|

-

Aria (Sopran): "Ricetti gramezza e

pavento" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kantate

"Amore traditore", BWV 203 - Leipzig

etwa 1735

|

|

14' 33" |

|

|

Solokantate

für Baß und cembalo |

|

|

A6 |

|

-

Aria (Baß): "Amore traditore"

|

6' 53" |

|

A7 |

|

-

Recitativo (Baß): "Voglio provar" |

0' 34" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Aria (Baß): "Chi in amore" |

7' 06" |

|

B2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Agnes Giebel, Sopran

(BWV 209)

Jacques

Villisech, Baß (BWV 203)

Frans Vester, Querflöte

(BWV 209)

Gustav Leonhardt, Cembalo

- BWV 209: Cembalo Martin Skowroneck,

Bremen 1960, nach einem italienischen

Model des 17. Jahrhubderts (zwei 8')

- BWV 203: Cembalo

Martin Skowroneck, Bremen 1962, nach

J. D. Dulcken, Antwerpen 1745)

LEONHARDT-CONSORT

- Marie Leonhardt, Violine (Jakob

Stainer 1676)

- Antoinette van den Hombergh, Violine

(Klotz, 18 Jahrh.)

- Wim ten Have, Viola (Giovanni

Tononi, 17. Jahrh.)

- Dijck Koster, Violoncello (Giovanni

Battista [II] Guadagnini, 1749)

Alle Instrumente in Barockmensur.

Stimmung ein Halbton unter normal

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Queekhoven, Breukelen

(Holland) - 8/9 Febbraio 1964

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9465-B (Stereo) - AWT

9465-C (Mono) | 1 LP - durata 31'

56" | (p) 1965 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics

"Secular Cantatas" | LC 6019 |

3984-25710-2 | 11 CDs - [CD 3:

Tracks 10-17 | (c) 2000 | ADD

Teldec Classics | LC 6019 |

3984-21711-2 | 1 CD - durata 68'

48" | (c) 1998 | ADD | (BWV 209)

|

|

|

Cover

|

|

Canaletto Belotto

"Piazetta und Riva degli Schiavoni

von der Meerseite" (Ausschnitt).

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

The cantata in

the broadest sense of the

word - whether as the church

cantata pr the patrician,

academic or courtly work of

musical homage and festivity

- accompanied the Arnstadt

and Mühlhausen organist, the

Weimar chamber musician and

court organist, the Köthen

conductor and finally the

Leipzig cantor of St.

Thomas'-Bach-all through his

creative life, although with

fluctuating intensity, with

interruptions and

vacillations that still are

problems to musicological

research down to this very

day. The earliest preserved

cantata ("Denn du wirst

meine Seele nicht in der

Hölle lassen") probably

dates, if it really is by

Bach, from the Arnstadt

period (1704) and is still

completely under the spell

of North and Central Grman

traditions. In the works of

his Mühlhausen years

(1707-08) - psalm cantatas,

festive music for the

changing of the cuncil and a

funeral work (the "Actus

tragicus") - we sense of the

first time something of what

raises Bach as a cantata

composer so much higher than

all his contemporaries: the

abolity to analyse even the

most feeble text with regard

to its form and content, to

grasp its theological

significance and to

interpret it out of its very

spiritual centre in musical

"speech" that is infinitely

subtle and infinitely

powerful in effect. In

Weimar (1708-17) new duties

pushed the cantata right

into the background to begin

with. It was not until the

Duke commissioned him to

write "new pieces monthly"

for the court services that

Bach once more turned to the

cantata during the years

1714-16, on texts written by

Erdmann Neumeister and

Salomo Franck. Barely thirty

cantatas can be ascribed to

these two years with a

reasonable degree of

certainty. It is most

remarkable that, on the

other and, no courtly

funeral music has been

preserved from the entire

Weimar period, although

there must have been a

considerable demand for such

works. It is conceivable

that many a lost work,

supplied with a new text by

Bach himself, lives on among

the Weimar church cantatas.

In the years Bach spent at

Köthen (1717-23), on the

other hand, it is the

composition of works for

courtly occasions of homage

and festivity that come to

the fore entirely in keeping

with Bahc's duties as Court

Conductor. It is only during

the last few months he spent

at Köthen that we find him

composing a series of church

cantatas once again, and

these were already intended

for Leipzig. It was in

Leipzig that the majoritz of

the great church cantatas

came into being, all of them

- according to the most

recent research - during his

first few years of office at

Leipzig and comprising

between three and a maximum

of five complete series for

all the Sundays and feast

days of the ecclesiastic

year. But just as suddently

as it began, this amazing

creative flow, in which this

magnificent series of

cantatas arose, appears to

have ended again. It is

possible that Bach's regular

composition of cantatas

stopped as early as 1726;

from 1729 at the latest it

is evident that other tasks

largely absorbed his

creative energy,

particularly the direction

of the students' Collegium

Musicum with its perpetual

demand for fashionable

instrumental music. More

than 50 cantatas for courtly

and civic occasions have

indeed been recorded from

later years, but considered

over a period of 24

years and compared with the

productivity of his first

years in Leipzig they do not

amount to very much. We are

left with the picture of an

enigmatic silence in a

sphere which has ever

counted as the central

category in Bach's creative

output.

But we only need cast a

superficial glance at the

more than 200 of the

master's cantatas that have

come down to us in order to

see that this conception of

their position in Bach's

total output is fully

justified. Bach has

investigated their texts

with regard to both their

meaning and their wording

with incomparable

penetration, piercing

intellect and unshakeable

faith, whether they are

passages from the Bible,

hymnus, sacred poems by his

contemporaries or sacredly

trimmed poetry for courtly

occasions. He has

transformed and interpreted

these texts through his

music with incomparable

powers of invention and

formation, he has revealed

their essence and, at the

same time, translated the

imagery and emotional

content of each of their

ideas into musical images

and emotions. The perfect

blending of word and note,

the combination of idea

synthesis and depiction of

each detail of the text, the

joint effect of the baroque

magnificence of the musical

forms and the highly

differentiated attention to

detail, the skillful balance

between contrapuntal,

melodic and harmonic means

in the service of the word

and, not least, the

inexhaustible fertility and

greatness of a musical

imagination that is able to

create from the most feeble

'occasional' text a world of

musical characters - all

this is what raises the

cantata composer Bach so

much higher than is own and

every other age and their

historically determined

character, and imparts a

lasting quality to his

works. It is not their texts

alone and not their music

alone that makes them

immortal - it is the

combination of word and note

into a higher unit, into a

new significance that first

imparts to them the power of

survival and makes them what

they are above all else:

perfect works of art.

|

|

|

|