|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9458-A - (p) 1964

|

|

| 5 LPs -

SCA 25022-T/1-5 - (c) 1972 |

|

| 2 CDs -

8.35778 XD - (c) 1989 |

|

| KONZERTE FÜR 3

CEMBALI & CEMBALOKONZERTE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Konzert

für 3 Cembali d-moll, BWV 1063 - 2

Violinen, Viola und Continuo

|

|

13' 30" |

|

|

-

(Allegro)

|

4' 57" |

|

A1

|

|

- Alla Siciliana

|

3' 53" |

|

A2

|

|

-

Allegro

|

5' 04" |

|

A3 |

|

Konzert

Nr. 8 d-moll für Cembalo, BWV 1059 -

Oboe, 2 Violinen, Viola und Continuo

(Rekonstrution: Gustav Leonhardt) *

|

|

15' 00" |

|

|

-

(Allegro)

|

6' 30" |

|

A4 |

|

-

Adagio (Cembalo ad libitum)

|

1' 06" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Presto

|

3' 42" |

|

B2 |

|

Konzert

für 3 Cembali C-dur, BWV 1064 - 2

Violinen, Viola und Continuo |

|

17' 00" |

|

|

-

Allegro |

6' 23" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Adagio |

5' 49" |

|

B4 |

|

-

Allegro

|

4' 40" |

|

B5 |

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav

LEONHARDT, Cembalo *

Anneke UITTENBOSCH, Cembalo

Alan CURTIS, Cembalo

|

DAS

LEONHARDT-CONSORT

- Marie Leonhardt, Antoinette van den

Hombergh, Violine

- Wim ten Have, Lodewijk de Boer, Viola

- Dijck Koster, Violoncello

- Fred Nijenhuis, Kontrabaß

Gustav LEONHARDT, Leitung

|

Instrumente:

- Cembalo I (Martin Skowroneck, Bremen 1962,

nach J. D. Dulcken, Amsterdam 1745)

- Cembalo II und III (Martin Skowroneck,

Bremen 1963 nach J. D. Dulcken, Amsterdam

1745)

- Violine (Jakob Stainer, 1676)

- Violine (Klotz, 18. Jahrh.)

- Viola (Giovanni Tononi, 17. Jahrh.)

- Viola (deutsch, 18. Jahrh.)

- Violoncello (Giovanni Battista [II]

Guadagnini, 1749

- Kontrabaß (deutsch, 18. Jahrh.)

Alle Instrumente in Barockmensur

Stimmung ein Halbton unter normal

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Hervormde Kerk,

Bennebroek (Holland) - 9/12

Ottobre 1963

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9458-A (Stereo) - AWT

9458-A (Mono) | 1 LP - durata 41'

30" | (p) 1964 | ANA

Telefunken

"Das Alte Werk" | SCA

25022-T/1-5 | 5 LPs - durata

212' 39" | (c) 1972 | ANA | (Sämtliche

Cembalokonzerte)

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics |

LC 3706 | 8.35778 XD | 3 CDs -

durata 76' 42" - 72' 00" - 63'

57" | (c) 1989 | ADD |

(Sämtliche Cembalokonzerte) |

|

|

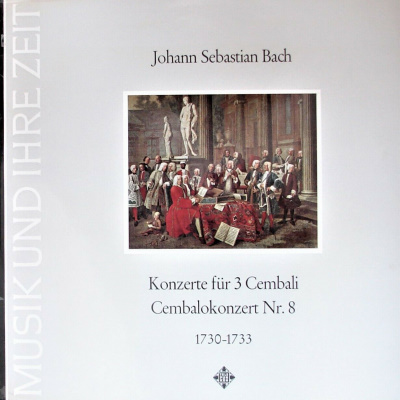

Cover

|

|

- |

|

|

Note |

|

"Hofmusik in

ismaning", aus dem Gemälde von

Peter Jakob Horemans (Original in

Bayerischen Nationalmuseum,

München).

|

|

|

|

|

Bach’s two

concertos for three

harpsichords have long been

widely known and admired by

music lovers - already in

1840, Liszt, Mendelssohn,

and Hiller performed the D

minor Concerto at the

Leipzig Gewandhaus with

acclaim. Seldom, however, in

this past century and a

quarter have the concertos

been heard in a manner at

all closely resembling their

composer’s intention. Until

recently, the convergence of

three harpsichords was in

itself a rarity, and even

today the assembling of

three individual and

authentic instruments of

‘equal strength is most

unusual, although vitally

essential to the proper

balance of the work. The

present recording employs

three very similar but not

identical harpsichords

which, unlike most modern

instruments, reproduce the

full resonance and quality

of tone usual in Bach’s day.

They are complemented not by

a modern string orchestra,

but by a small complement of

soloists, whose Baroque

instruments blend, or

occasionally sing out, but

never enshroud with a heavy

mantle of vibrato sound the

clarity and brilliance of

the solo parts. The addition

of a fourth harpsichord for

the continuo, declared

necessary by certain German

scholars, is unjustified and

superfluous in these

concertos. In the few

figured bass passages

(second movement of the C

major) the continuo function

may be divided among the

three keyboards, at the

discretion of the

performers. More problematic

is the division of parts in

the second movement of the D

minor. Here the beautifully

lilting melody, in the

rhythm of a siciliano, has

come down to us scored for

violin doubled - or rather

quadrupled - by all three

harpsichords, whose parts

are pedantically identical

in the tuttis. Such

heavy-handed doubling is

most un-Bachian, and even if

this piece is not his, would

be puzzling in a work

otherwise of such quality.

It is hardly surprising to

learn that this movement has

been preserved not in an

autograph, but only in

copies made long after

Bach’s death. Probably the

doubling was the work of an

unimaginative copyist no

longer accustomed to

continuo practice. This

recording restores the

melody to the violin and an

accompanying role to the

harpsichords.

The man to whom we owe the

most authentic copy of these

two concertos was Johann

Gottfried Palschau

(1741-1813), a keyboard

player and composer born in

Hamburg, who travelled to

Riga, studied there with

Bach’s well-known pupil,

Müthel, and settled in

Petersburg. We might well

imagine that he obtained

copies of the concertos from

Müthel, and that therefore

the ascription to J. S. Bach

is to be accepted. No

scholar has yet brought

forth credible evidence to

the contrary. It is all the

more remarkable, then, to

find that Palschau omits the

alla siciliana

movement from his otherwise

careful copy. It is not only

the doubling which makes

this movement dubious. The bel

canto cadential

figures are the work of a

German with sympathies for

Italian opera (more

Handelian than Bachian), and

the form - 8-bar tutti,

8-bar solo, 24-bar tutti,

24-bar solo, cadenza - is

very unlike Bach’s

sicilianas or other slow

movements. Could it have

been written by Wilhelm

Friedemann, whose concerto

for two harpsichords long

passed for the work of his

father? We can never be

certain. Nor shall we ever

know whether these concertos

were original compositions

or transcriptions. Prof.

Schering felt the C major

must have originally been

written for three violins,

because of solo passages

where the left hands are

doubled, the right hands

varied. However; the

opposite is also

occasionally true, and the

extraordinary sound of

measures 80-85 of the first

movement, with its

independently arpeggiated

bass lines in the solo left

hands, would be quite

impossible in another

medium. In the last movement

of the D minor, moreover,

the unusually long, driving

sequence of the first

harpsichord would be

unthinkable on anything but

a keyboard: the upper line

alone covers a range of

three and a half octaves of

unbroken sixteenths.

At the end of the autograph

manuscript of Bach’s seventh

Harpsichord Concerto is the

beginning of an eighth.

After nine measures, just

when the solo is to enter,

the fragment ends. The loss

of the rest, after such a

tantalizing opening, has

given rise to the

lamentations of Bach

scholars - and to the

remarkable reconstruction by

Gustav Leonhardt here

recorded. The nine measures

correspond with the opening

of Cantata 35, “Geist und

Seele wird verwirret”

(1726), though Bach has

dropped the second oboe and

the taille. Moreover, in the

fourth measure he has

drastically altered the

theme by adding syncopations

and upward scalar sweeps, an

intensification which

astounds us as a stroke of

genius and surely indicates

that the concerto followed

the cantata (though Spitta,

II, 278, strangely assumed

the opposite). Leonhardt has

revised the instrumental

parts of the cantata along

the lines indicated by the

fragment and, with the

obligato organ part as a

basis, invented an idiomatic

harpsichord part as Bach, or

another 18th-century

performer, might have done.

Inasmuch as the Seconda

Parte of the same

cantata is opened by another

instrumental Sinfonia

with organ solo, it seems

likely that this would have

formed the last movement of

the concerto. The orchestral

parts are practically

unaltered in Leonhardt’s

version. Spitta’s notion

that the opening da capo

aria for alto would have

served as middle movement

seems untenable, most

obviously for formal

reasons. For lack of a

full-length movement,

Leonhardt has improvised a

prelude to an orchestral

Phrygian cadence, parallel

to that in the Third

Brandenburg Concerto.

The most likely use for

harpsichord concertos in

Bach’s Leipzig activities

would have been the weekly

meetings of the Collegium

Musicum founded by Telemann

and taken over by Bach in

1729. It is pleasant to

think of him presiding at

the Friday evening sessions,

where Gottfried Zimmermann’s

coffee-house on

Catherinenstrasse would have

been jammed full of

harpsichords and - one hopes

- some appreciative

coffee-drinking students. As

Bach’s secretary enticingly

wrote to a friend in 1739,

“...he will begin the

Collegium Musicum this

Friday, and will perform

some music in the first week

of the Fair for the birthday

of His Royal Majesty. It

will certainly be worth

listening to.”

Alan

S. Curtis

|

|

|

|