|

|

1 LP -

SAWT 9457-B - (p) 1964

|

|

| 1 LP -

6.42091 AN - (p) 1964 |

|

| 1 CD -

3984-21354-2 - (c) 1998 |

|

| QUODLIBET -

KANONS - LIEDER - INSTRUMENTALSTÜCKE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Präludium

F-dur, BWV 927 - aus: Neun kleine

Präludien, aus dem Klavierbüchlein für

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Köthen 1720/21

|

|

0' 40" |

A1 |

|

Quodlibet

(Fragment) für vier Singstimmen mit

Generalbaß, BWV 524 - wahrscheinlich

1707, Mülhausen |

|

9' 30" |

A2 |

|

Präludium

E-dur, BWV 937 - aus: Neun kleine

Präludien, aus dem Klavierbüchlein für

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Köthen 1720/21 |

|

1' 23" |

A3

|

|

Präludium g-moll, BWV 929 -

aus: Neun kleine Präludien, aus dem

Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann

Bach, Köthen 1720/21 |

|

1' 00" |

A4

|

|

So

oft ich meine Tobacks-Pfeife, BWV

515a - Erbauliche Gedanken eines

Tobackrauchers aus dem Klavier-büchlein

für Anna Magdalena Bach, 1725 |

|

3' 12" |

A5 |

|

Präludium

d-moll, BWV 940 - aus: Neun kleine

Präludien, aus dem Klavierbüchlein für

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Köthen 1720/21 |

|

0' 47" |

A6 |

|

Kanon

zu 2 Stimmen, BWV 1075 - "Canon a 2.

perpetuus", Leipzig, 1734 |

|

1' 05" |

A7 |

|

Kanon

zu sieben (acht) Stimmen, BWV 1078 -

"fa mi, et Mi fa est tota Musica",

Leipzig, 1749 |

|

0' 35" |

A8 |

|

Präludium

D-dur, BWV 925 - aus: Neun kleine

Präludien, aus dem Klavierbüchlein für

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Köthen 1720/21 |

|

1' 15" |

A9 |

|

Gib

dich zufrieden und sei stille, BWV

511 - aus dem: Klavierbüchlein für Anna

Magdalena Bach, 1725 |

|

4' 10" |

A10 |

|

Kanon

zu vier Stimmen, BWV 1073 - "Canon a

4. Voc: perpetuus", Weimar 1713 |

|

1' 15" |

B1 |

|

Kanon

zu drei (fünf) Stimmen, BWV 1077 -

"Canone doppio sopr'il Soggetto", Leipzig

1747 |

|

1' 10" |

B2 |

|

O

Herzensangst, o Bongigkeit und Zagen,

BWV 400 - aus den "Chorälen für vier

Singstimmen" |

|

1' 40" |

B3 |

|

Nicht

so traurig, nicht so sehr, BWV 384 -

aus den "Chorälen für vier Singstimmen" |

|

2' 25" |

B4 |

|

Dir,

dir, Jehova, will ich singen, BWV

452 - aus dem: Klavierbüchlein für Anna

Magdalena Bach, 1725 |

|

2' 40" |

B5 |

|

Präludium

C-dur, BWV 939 - aus: Neun kleine

Präludien, aus dem Klavierbüchlein für

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Köthen 1720/21 |

|

0' 30" |

B6 |

|

Fuge

C-dur, BWV 952 - Köthen etwa 1720 |

|

2' 05" |

B7 |

|

Was

betrübst du dich, mein Herze, BWV

423 - aus den "Chorälen für vier

Singstimmen" |

|

3' 30" |

B8 |

|

Vergiß

mein nicht, mein allerliebster Gott,

BWV 505 - Schmellis Gesangbuch, Leipzig

1736 |

|

2' 00" |

B9 |

|

Wer

nur den lieben Gott läßt walten, BWV

691 (Choralbearb.) in

Kirnbergers Sammlung. Wahrscheinlich

Weimar 1708 bis 1717 |

|

1' 45" |

B10 |

|

Wer

nur den lieben Gott läßt walten, BWV

434 - aus den "Chorälen für vier

Singstimmen" |

|

2' 55" |

B11 |

|

Wer

nur den lieben Gott läßt walten, BWV

690 (Choralbearb.) in Kirnbergers

Sammlung. Wahrscheinlich Weimar 1708 bis

1717

|

|

1' 50" |

B12 |

|

|

|

|

|

Agnes

Giebel, Sopran

Marie Luise Gilles, Alt

Bert van t'Hoff, Tenor

Peter Christoph Runge, Baß

|

DAS

LEONHARDT-CONSORT

Gustav Leonhardt, Cembalo und

Orgel

Anner Bylsma, Violoncello

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Haus Queekhoven,

Breukelen (Holland) - 12/20

Febbraio 1964

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Dieter Thomsen

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" | SAWT 9457-B (Stereo) - AWT

9457-C (Mono) | 1 LP - durata 47'

02" | (p) 1964 | ANA

Telefunken

"Meister der Musik" | SAWT

9457-B | 1 LP - durata 47' 02" |

(p) 1964 | ANA | Riedizione

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec Classics |

LC 6019 | 3984-21354-2 | 1 CD -

durata 73' 43" | (c) 1998 | ADD |

|

|

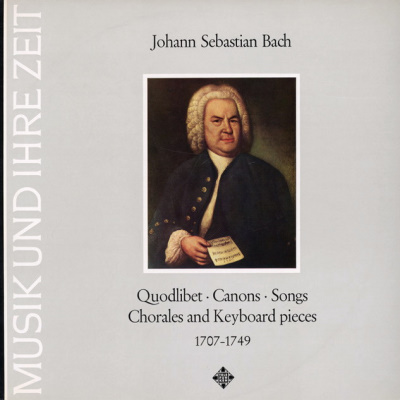

Cover

|

|

"Johann Sebastian

Bach", Ölgemälde von Elias

Gottlieb Haussmann.

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bach's “inner

biography”, his domestic and

artistic “day to day

existence”, are less known

to us than the private lives

of any other great composers

of the modern age. And yet

there are some works of his

- by no means few in number

- that are not very

pretentious and therefore

not very well known, but

which, in their very

modesty, are able to give us

clear information about the

composer's everyday life.

These are the little

practice pieces for the

domestic use of the musical

Bach family, the partly

serious, partly gay songs

and arias and the group of

compositions written for

special occasions or as

favours, which include both

the high-spirited Quodlibet

and the little but highly

complex instrumental canons

of the later years. The

wealth of forms and nuances

that Bach was able to impart

to these "little works",

their cpmbination of naive

charm, apparent casualness,

intimacy of private domestic

music-making or expert

contemplation of little

masterpieces of part-writing

and strictest formation into

the totality of a work of

art that is only outwardly

small and inconspicuous, are

movingly and astonishingly

manifested even in such a

limited selection as can be

accommodated of our record.

The “Little” Preludes -

altogether twenty have been

preserved for us - probably

all date from Bach's Köthen

period (1717-23), and have

partly come down to us in

the Little Keyboard Book for

Wilhelm Friedemann. They

were thus intended as simple

practice and study pieces

for the prospective keyboard

player and composer. In

Bach's hands they have

become real little works of

art, meticulously formulated

in spite of their outward

modesty and each with its

own clearly defined

character of expression

(quite apart from the fact

that each prelude, faithful

to its educational purpose,

presents its own problems of

fingering and articulation).

The little Fugue in C major,

BWV 952, almost certainly

belongs to the same

category; its authenticity,

however, has not been

completely established.

Also belonging to the

domestic circle of the Bach

family are the songs which

Bach himself and his second

wife Anna Magdalena wrote

down in the latter's second

“Notenbuch" (1725), although

these did not serve any

didactic purpose. They are

simple melodies with

continuo accompaniment,

which pour out their fervent

and tender expression

entirely from the intense

melodic writing of the voice

part, their harmony being

kept strikingly simple. (The

little “Aria’’ BWV 505 is

taken from the Schemelli

Song Book which was

published in 1736, but is

sure to have originated in

the same mode of music

making.) But the

twenty-four-year-old wife of

the Cantor of St. Thomas's

felt by no means only at

home in the world of

contemplative family

worship, as is shown by the

“cosy” humour of the Tobacco

Pipe Song, which also

provides evidence of the

fashion of "tobacco

intoxication" which had

taken a powerful hold of the

middle classes in Bach's

day.

Bach’s humour finds an even

more robust and unrestricted

expression than in the above

song in the fragmentary

Wedding Quodlibet. The

high-spirited text, in which

lines from various sources

are thrown together, abounds

in vigorous jokes and

allusions; the no less

high-spirited music is full

of folk song quotations and

musical jests. The whole

reflects the slightly

alcoholic revelry of a

proper wedding celebration

among citizens of the

baroque age, showing Bach

the “Cantor” from a most

unaccustomed but very

amiable side.

On the other hand, the

instrumental canons which

Bach wrote, mostly in the

latter years at Leipzig, in

family albums or dedicated

to his friends and patrons

on other occasions match

more closely the traditional

picture of the composer. The

way in which the ageing

master turned to profound

musical speculation,

demonstrated most

maggnificently in the Art of

Fugue and the Musical

Offering, also appears here

on a modest scale yet with

skillful and profound

results. The subtly

constructed little works,

which demand exact study and

enjoyment of every detail,

pass by almost too

fleetingly as an aural

experience.

Also austere and earnest in

character are finally the

four-part chorales, which

were first published after

Bach's death by C.P.E. Bach

and J.P. Kirnberger. In

their accurate and subtle

interpretation of the words

and their magnificent wealth

of harmony they stand, equal

in quality, alongside the

great chorale settings of

the cantatas; like the

latter, they combine the

simple chorale melodies

(those selected here all

being by Bach himself except

for BWV 434) in the soprano

with a fine web of lower

voices, the “voice of the

congregation” with its

individual interpretations,

to form a profound symbolic

unity. Turning to the purely

instrumental field, we find

this relationship finally

prevailing in the early

chorale arrangements for the

organ as well, which were

probably composed at Weimar

(1708-1717). The three last

pieces on our record - two

of these instrumental

chorale arrangements and one

vocal treatment of the same

chorale - clearly

demonstrate the basic

similarity as well as the

subtle differences between

these two different types of

performance and tone within

the same category.

|

|

|

|