|

|

1 CD -

SK 53 114 - (p) 1993

|

|

| WORKS FOR

KEYBOARD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Georg BÖHM (1661-1733) |

Praeludium

in G minor |

|

6' 56" |

1 |

|

Suite

in C minor *

|

|

6' 26" |

|

|

-

Allemande

|

2' 16" |

|

2

|

|

- Courante |

1' 01" |

|

3

|

|

-

Sarabande |

1' 54" |

|

4 |

|

- Gigue |

1' 25" |

|

5 |

|

Capriccio in D

major |

|

4' 51" |

6

|

|

Choralpartita

"Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt

walten" - 7 Variations |

|

8' 18" |

7 |

|

Ouverture in D

major |

|

14' 54" |

|

|

-

Ouverture |

4' 09" |

|

8

|

|

- Air |

1' 43" |

|

9 |

|

-

Rigaudon-Trio |

2' 32" |

|

10 |

|

-

Rondeau |

1' 44" |

|

11 |

|

-

Menuet |

1' 09" |

|

12 |

|

-

Chaconne |

3' 37" |

|

13 |

|

Suite

in F minor |

|

7'

42"

|

|

|

-

Allemande |

2' 43" |

|

14 |

|

-

Courante |

1' 06" |

|

15 |

|

-

Sarabande |

1' 26" |

|

16 |

|

-

Ciaccona (Passacaille) |

2' 27" |

|

17 |

|

Choralpartita

"Ach wie nightig, ach wie

flüchtig" - 8 Variations |

|

5' 10" |

18 |

|

Suite

in E-flat major *

|

|

8' 14" |

|

|

-

Allemande |

3' 10" |

|

19 |

|

-

Courante |

1' 33" |

|

20 |

|

-

Sarabande |

1' 37" |

|

21 |

|

-

Gigue |

1' 54" |

|

22 |

|

|

|

|

Gustav LEONHARDT,

Harpsichord & Clavichord

|

|

| (Harpsichord by Bruce

Kennedy, Amsterdam, 1986 after M. Mieke,

Berlin, early 18th century) |

|

(Clavichord by Martin

Skowroneck, Bremen, 1967) *

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lutherse Kerk,

Haarlem (Holland) - 31 Agosto / 1

Settembre 1992 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording supervisor |

|

Wolf Erichson |

|

|

Recording

Engineer / Editing

|

|

Stephan Schellmann

(Tritonus) |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Nessuna |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Sony "Vivarte" | LC

6868 | SK 53 114 | 1 CD - durata

63' 22" | (p) 1993 | DDD |

|

|

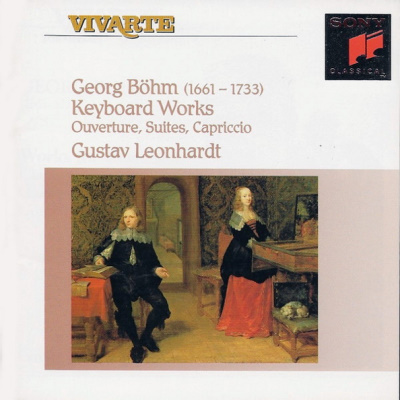

Cover Art

|

|

"Der junge Gelehrte

und seine Schwester" by Gonzales

Coques.

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Georg Böhm was

horn in the Thuringian

village of Hohenkirchen near

Ohrdruf on Septemher 2,

1661. He was the son of the

local schoolmaster and

organist, Balthasar Böhm,

whose wife Martha, née

Schambach, hailed from an

equally musical family.

Following his father's early

death, Böhm

enrolled at the Lateinschule

at Goldbach and, from 1678,

at the Gymnasium at Gotha.

He matriculated at the

University of Jena on August

28, 1684. Nothing else is

known about his studies

there, or about his musical

development, although a

glance at the flourishing

musical scene in Central

Germany at this time, with

its countless Kantors and

organists, suggests that it

is here that the roots of

his musicianship lie. His

earliest links with northern

Germany were forged during

his years of study in Jena.

It is clear from the

University’s records, for

example, that two of his

fellow students were from

Hamburg, where their fathers

were active in the city’s

principal churches, the

Katharinenkirche and the

Nikolaikirche. With the

completion of his studies in

Jena we lose all trace of Böhm

for a number of years. We

know only that at some date

after 1690 - and certainly

by April 1693, when his

second son was baptized - he

had settled in St. Jacobi,

one of Hamburg's five

parishes, each of which was

named after one of the

city’s five main churches.

Although Böhm never

held the post of organist in

Hamhurg, he was unanimously

elected organist of the

Johanniskirche in Lüneburg

on August 30, 1698, a post

which he retained until his

death on May 18, 1733.

Although nothing definite is

known about Böhm’s

musical training, his works

contain evidence of a numher

of different influences.

Further indications come

from the manuscript sources

of his works, which have

survived only in the form of

copies: there are no extant

holographs. Moreover,

although the earliest

influences on Böhm

must date back to his days

at school and university in

Central Germany, even his

early works survive only in

copies made during his

Lünehurg years.

There is no doubt that a

considerable influence on

the young Böhm

was exercised by Johann

Pachelbel (1653-1706), who

from 1678 to 1690 was

organist at the

Predigerkirche in Erfurt, a

town situated only some

sixteen miles distant from

Gotha. It is entirely

conceivable that Böhm

visited Erfurt during the

summer of 1684, while on his

way to Jena. Pachelbel's

influence is particular

clear in the case of Böhm's

chorale partite, many of

which have survived in the

same manuscript sources as

Pachelbel’s own works.

Chorale partite are

variations on a church

anthem or hymn and, in Böhm's

day, were normally intended

for domestic consumption.

Today, by contrast, they are

generally played on the

organ and, therefore, in

church. All the works

recorded here, however, are

harpsichord pieces, as is

clear from the low A’ in Ach

wie nichtig, ach wie

flüchtig. (The organ

keyboard extended only down

to C.) Moreover, the low A’

suggests that it was a

relatively large harpsichord

which was used. Equally

typical of harpsichord

writing is the ending of Wer

nur den lieben Gott läßt

walten: with its

broken chords and octave

intervals in the bass, the

presto section is designed

to bring the work to a

brilliant, resounding

conclusion, an effect which

the sudden change of tempo

helps to underline. It is Böhm's

chorale partite, above all,

that demonstrably influenced

Johann Sebastian Bach.

With his move to Hamburg - a

leading centre of music at

this time - Böhm

not only left behind his

Central German homeland, he

also found himself faced by

a multiplicity of new

impressions and stylistic

trends associated with the

rich north German tradition.

In Hamburg there were

important instrument makers,

a long history of secular

and religious music, an

opera house, and churches

with splendid organs. The

co-founder of the "Oper am

Gänsemarkt", the elderly

Johann Adam Reincken

(1623-1722), was organist at

the Katharinenkirche, which

boasted a magnificent,

four-manual instrument. Arp

Schnitger (1648-1719) had

been active in the city

since 1682 and was

responsible for four-manual

organs at the Nikolaikirche

(1682-87) and Jacobikirche

(1689-93).

Another composer on friendly

terms with Reincken was the

Lübeck organist, Dietrich

Buxtehude (c.1637-1707).

Like Reincken, Buxtehude had

written a number of keyboard

suites playable on either

harpsichord or clavichord

which adopted the

four-movement form -

allemande, courante,

sarabande and gigue -

established by Johann Jacob

Froberger (1616-1667). Böhm

himself must have known at

least some of these suites,

since the majority of his

own suites are similar not

only in their structure but

also in their use of certain

features such as the “style

brisé”, a style whose

origins may be sought in

French lute music. In much

the same way, the variation

technique that Böhm uses in

the Allemande and Courante

of his F minor Suite is

clearly indebted to these

models. Of particular

interest, here is an

anonymous volume published

by Étienne Roger of

Amsterdam, it contains not

only the F minor Suite

recorded here but also three

Fugues by Pachelbel, two

works by Reincken and at

least one Suite that can be

attributed with some

certainty to Buxtehude.

Whereas the final movement

of the F minor Suite is

headed Ciaccona in

the manuscript source, it is

described as a Passacaille

in Rogers printed version,

thereby providing yet

further proof of the

terminological confusion

that existed between the

chaconne and passacaglia as

genres. This final movement

replaces the gigue in Böhm's

Suite, which is otherwise

orientated to north Gertnan

stylistic models.

The clavichord was much

esteemed in Germany as a

domestic instrument, a

popular and viable

alternative to the lute,

which was itself often used

in suites. Harpsichord music

of the seventeenth and early

eighteenth centuries

frequently sounds as good,

if not better, on the

sensitive clavichord, as may

be heard on the present

release, where both the

E-flat major and C minor

Suites have been recorded on

such an instrument.

According to research

undertaken by Jean-Claude

Zehnder and published in the

“Bach-Jahrbuch 1988", Böhm

was active at the Hamburg

Opera, where he was

introduced to French taste

by Lully's pupil, Johann

Sigismund Kusser (1660-1727)

Kusser had published six

orchestral overtures (or

suites) in 1682 in his Composition

de musique suivant la

Méthode Françoise.

Böhm’s D major Suite differs

in two respects from the

other suites discussed

hitherto. In the first

place, it is generally

regarded as the first

surviving example of an

overture suite for

harpsichord (a form which

had previously been the

preserve of orchestral

music), the cycle being

modelled on the French

ballet suite, with a

French-style overture (slow

- fast - slow) followed by a

series of dance movements.

Second, the piece also

differs from Böhm's other

harpsichord works from a

technical point of view,

inasmuch as it is less

obviously suited to the

keyboard. The solution to

this mystery may be found in

the workls only source, the

socalled

“Andreas-Bach-Buch", which

suggests, in all likelihood,

that the D major Suite is a

harpsichord transcription of

an earlier orchestral piece.

The original is by Böhm, the

transcription possibly by

Johann Sebastian Bach’s

elder brother, Johann

Christoph (1671-1721), who

was responsible for

compiling the manuscript as

a whole. We are dealing here

with the same kind of

elaborate adaptation as that

undertaken by Johann

Sebastian Bach himself when

transcribing other

composers’ concertos for

solo harpsichord or organ.

The D major Capriccio falls

into three thematically

related, fugue-like

sections. The sense of

tension is increased by the

fact that each section has a

different tempo marking, so

that the music seems to

accelerate, before being

brought to a purposeful

conclusion.

Böhm's G minor Prelude is

his most original

contribution to the

harpsichord repertory, its

composition being very much

"sui generis". G minor

chords sprout forth, so to

speak, from a pedal point on

G; cadenzas, modulations and

sequences lead to D major,

thence to F major and back

to G minor. A brief,

surprising and improvisatory

Adagio section then follows,

leading the musical

development to a full

cadence in D major, which

gives way in turn to a

magisterial Fugue, the

subject of which is a richly

decorated, descending line

structured around five

notes. The Fugue is followed

by a series of virtuoso

broken chords which appear,

as it were, to mirror the

opening, before majestically

full-toned chords bring the

work to an end.

Harry

Joelson-Strohbach

(Translation:

© 1993 Stewart Spencer)

|

|

|

|