|

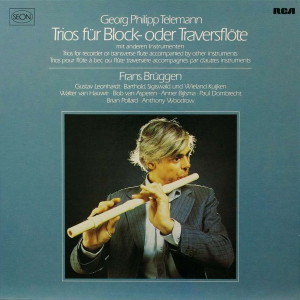

2 LPs

- RL 30343 - (p) 1979

|

|

| 2 CDs -

SB2K 60883 - (c) 1999 |

|

TRIOS FÜR BLOCK- ODER

TRAVERSFLÖTE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Georg Philipp TELEMANN (1681-1767) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1. |

Trio

in F Major for Recorder, Bass Viol

and B.c. (Vivace-Mesto-Allegro) -

from "Essercizii Musici", Nr. 7 (Hamburg,

after 1740) |

|

7' 04" |

A1 |

| 2. |

Trio

in D Minor for Transverse Flute,

Oboe and B.c. (Largo-Allegro-Affettuoso-Presto)

- from "Essercizii Musici", Nr. 11

(Hamburg, after 1740) |

*

|

8' 20" |

A2

|

| 3. |

Trio

in B-flat Major for Recorder,

Harpsichord obbligato and B.c. (Dolce-Vivace-Siciliana-Vivace)

- from "Essercizii Musici", Nr. 8

(Hamburg, after 1740) |

|

8' 08" |

A3 |

| 4. |

Introduzzione

a tre in C Major for 2 Recordersund

B.c. (I-II-III-IV-V-VI-VII-VIII) -

(from "Der getreue Musikmeister" (Hamburg,

1728-29) |

* |

12' 59" |

B1 |

| 5. |

Trio

in A Major for Transverse Flute,

Harpsichord obbligato and B.c. (Largo-Allegro-Largo-Vivace)

- from "Essercizii Musici", Nr. 4

(Hamburg, after 1740) |

* |

10' 50" |

B2 |

| 6. |

Trio

in D Minor for Recorder, Pardessus

de Viol and B.c. (Andante-Vivace-Adagio-Allegro)

- from Darmstädter Manuskript |

|

6' 50" |

C1 |

| 7. |

Scherzo

in E Major for 2 Transverse Flutes

and B.c. (Vivace-Largo-Vivace) -

from "3Trietti Metodici e 3 Scherzi", Nr.

2 (Hamburg, 1731) |

* |

7' 53" |

C2 |

8.

|

Trio

in A Minor for Recorder, Violin and

B.c. (Affettuoso-Vivace-Grave-Menuet,

Trio, Menuet) - from "Sechs Trios",

Nr. 2 (Frankfurt, 1718) |

|

9' 46" |

C3 |

9.

|

Trio

in D Minor for Recorder, Oboe and

B.c. (Largo-Vivace-Andante-Allegro)

- from "Essercizii Musici", Nr. 1

(Hamburg, after 1740) |

* |

11' 30" |

D1 |

10.

|

Trio

in E Major for Transverse Flute,

Violin and B.c. (Soave-Presto-Andante-Scherzando)

- from "Essercizii Musici", Nr. 9

(Hamburg, after 1740) |

|

7' 07" |

D2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. |

2. |

3. |

4. |

5. |

6. |

7. |

8.

|

9. |

10. |

|

Frans

Brüggen, Recorder (Jan

Steenbergen, Amsterdam, first half of 18th

century)

|

* |

|

*

|

*

|

|

*

|

|

*

|

*

|

|

|

Frans

Brüggen, Transverse Flute

(Thomas Stanesby, Jr., London, c. 1740)

|

|

*

|

|

|

*

|

|

*

|

|

|

*

|

|

Walter

van Hauwe, Recorder (P. J.

Bressan, London, ca. 1720)

|

|

|

|

*

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Barthold

Kuijken, Transverse Flute

(Godefroid A. Rottenburgh, Brussels, c.

1750-60)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*

|

|

|

|

|

Paul

Dombrecht, Oboe (Richard

Haka, Amsterdam, c. 1700)

|

|

*

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*

|

|

|

Wieland

Kuijken, Bass Viol (South

Germany [Tyrol], first half of the 18th

century, 7-string)

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wieland

Kuijken, Pardessus de Viol

(Feyzcan, Bordeaux, 1753)

|

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sigiswald

Kuijken, Violin (Giovanni

Granciano, Milan, c. 1700) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*

|

|

*

|

|

Bob

van Asperen, Harpsichord

(Rainer Schütze, Heidelberg, after J. D.

Dulcken)

|

|

|

*

|

|

*

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Continuo: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Anner

Bylsma, Cello (Matteo

Goffriller, Venice, 1699)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Anthony

Woodrow, Double bass

(Maggini School, Italy, c. 1740)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Brian

Pollard, Bassoon (Leonard

Pollard, 1977, copy after Caleb Gedney,

London)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Gustav

Leonhardt, Harpsichord

(William Dowd, Paris, 1975, after

Blanchet)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lutherse Kerk,

Haarlem (Holland):

- 20/21 Febbraio 1978

- 26/28 Settembre 1978 (*)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Recording Supervisor |

|

Wolf Erichson

|

|

|

Recording Engineer

|

|

Teije van Geest

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Seon (RCA Red Seal) |

RL 30343 | 2 LPs - durata 48' 27"

- 44' 06" | (p) 1979 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Sony | SB2K 60883 | 2

CDs - durata 48' 27" - 44' 06" |

(c) 1999 | ADD

|

|

|

Original Cover

|

|

Foto: Kunio Terunuma,

Tokio

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

The sonata

(derived from the Italian

verb sonare, to

sound) was originally a

piece to be sounded rather

than sung, or as the

dictionary compiler Janovka

put it in 1701, “a grave and

imposing musical work for

any sort of instruments”. In

the Baroque era sonatas were

usually written for one or

more melody instruments with

the flexible accompaniment of

the basso continuo - a bass

line, with or without figures

indicating harmonies, that

could be performed by a bass

instrument and/or a chordal

instrument, as the

circumstances of performance

dictated. The broad trend

during the era led from

sonatas for several

instruments and basso

continuo towards those for

one instrument and basso

continuo (solos).

Between these extreme

combinations, beginning as

early as Cima’s sonatas of

1610 and reaching a

numerical and musical peak

at the end of the 17th

century, came the trio

sonata (known then as sonata

a tre or plain trio).

The trio setting of two

melody instruments and basso

continuo, largely ignored in

performance today in favour

of the more concert-worthy

solo sonata, was in fact

“the most characteristic and

numerous setting not only of

the Baroque sonata but of

all Baroque instrumental

music, not to mention

considerable vocal music”

(William S. Newman, The

Sonata in the Baroque Era).

For Georg Philipp Telemann

and other German composers

of the early 18th century,

the standard in trio sonata

composition was set by the

great Italian violinist and

composer Arcangelo Corelli,

whose four sets of twelve

sonatas for two violins and

basso continuo (first

published

1681/1685/1689/1694)

achieved the distinction of

no fewer than 78 reprints in

his lifetime, 30 of these

outside Italy. Corelli

established a vernacular

language for the trio sonata

- balanced, moderate,

precise, refined - that

became internationally known

and “to ye musicians like ye

bread of life” (Roger North,

1728). His sonatas’

deliberate avoidance of

virtuosity enabled

performance by professional

musicians and amateurs

alike. The Germans were also

influenced by C0relli’s

careful craftsmanship, the

principle of equality of the

upper parts, the active

melodic participation of the

bass, the

slow-fast-slow-fast order of

movements of his sonate

da chiesa, and the

fugal fast movements. In his

Lebens-Lauff (1718)

and Selbstbiographie

(1739), Telemann

acknowledges his debt to

Corelli and records the

esteem in which his own trio

sonatas were held for their

essentially Corellian

virtues. He confesses that

the composition of virtuoso

concertos “was never close

to my heart”; he has “a

greater taste” for the

sonata, and “I have been

persuaded particularly that

the trio showed my greatest

strength, because I so

arranged it that one part

should have as much to

perform as the other”.

Recalling the period he

spent at the ducal court at

Eisenach (1707-12) he

writes: “I concentrated

especially on writing trio

sonatas here, always

arranging that the second

part seemed to be the first

part and the bass a natural

melody in close harmony with

the upper parts, and every

note in its only conceivable

and rightful place. It was

flatteringly said that this

genre displayed my powers at

their best”. His trio

sonatas were also singled

out for praise by such

eminent theorists as Scheibe

(1740) and Quantz (1752).

This astonishigly fluent and

prolific composer has left

about 145 trio sonatas,

about 60 of which were

published in his lifetime

(the bulk after 1730),

mainly issued and engraved

by himself. All the sonatas

circulated in manuscript

throughout Germany and as

far afield as France and

Sweden. For a musician at

that time, when music was

needed, he wrote it.

Telemann’s trio sonatas were

written, firstly, for courts

such as Eisenach, Darmstadt,

Dresden and Schwerin, to be

performed at “entertainments

given by great princes and

lords, for receptions of

distinguished guests and at

state banquets [and]

serenades” (George Muifat,

1701). Secondly, for public

concerts, such as those of

the Collegia Musica

he himself directed in

Leipzig, Frankfurt and

Hamburg. But perhaps most

significantly, and

increasingly throughout his

life, they catered for the

needs of the growing numbers

of musical amateurs - for

the various societies, who

depended on printed music or

on whatever their directors

or other composers could

supply them with, and for

individual households, who

needed Hausmusik.

The purposes for which these

trio sonatas were written

are confirmed by the

instrumentation. For the

courts Telemann sometimes

wrote for unusual

combinations such as

recorder or oboe with pardessus

de viole [3], flute or

violin with oboe d’amore, or

violin and bassoon. Over

half of the sonatas,

however, including almost

all of the published ones,

were written for violins or

flutes (separately or

together) - the most popular

amateur instruments at that

time. Telemann’s great final

collection Essercizii

Musici also includes

sonatas for the other

important amateur

instruments - recorder,

oboe, viola da gamba and

harpsichord [4-6, 7-10]. For

this collection Telemann

created four unique sonatas

for a melody instrument

(flute, oboe, recorder, viola

da gamba), obligato

harpsichord and basso

continuo [5, 9]; that is, as

well as a fully-realised

keyboard part, there is a

figured bass for a bass

instrument and/or another

chordal instrument. This

genre lies between the older

style of trio sonata and the

new style of sonata for a

melody instrument with

obligato keyboard pioneered

by such composers as J. S.

Bach (violin BWV 1014-18,

viola da gamba BWV 1027-29,

flute BWV 1030-32. This

collection also includes a

sonata for recorder, viola

da gamba and basso continuo

[4] - a combination unique

for Telemann and rare

elsewhere. Often Telemann

offered his amateur audience

flexibility of

instrumentation. For

example, the trio sonata

from his Der getreue

Music-Meister [1] (a

musical periodical for

households on subscription)

can be performed not only by

two recorders in C major or

two flutes or violins in A

major, but also by more than

one instrument to a part.

Like Corelli, Telemann for

the most part avoided great

technical demands in his

trio sonatas. He was able to

do so without “writing down”

to his audience because he

himself played the

harpsichord, violin and

recorder to virtuoso

standard and was competent

on the flute, oboe, viola da

gamba etc. He could

therefore write for all

these instruments with

personal knowledge of their

glories, difficulties and

idiosyncrasies. Many a

difficult-sounding passage

“lies under the fingers”.

Like other German composers

of his day, Telemann tried

to create a musical style

that would be pleasing to

all nations and all manner

of men. In doing so he tied

together his age’s loose

strands of national style

(French, Italian),

counterpoint or homophony,

art music or folk music,

elite music or popular

music, professional music or

amateur music. His style is,

as Sir John Hawkins said of

Corelli’s, “equally

intelligible to the learned

and unlearned” - popular,

uncomplicated and

entertaining. He is

progressive in striving for

the “singing” melody he

recommended to young

composers (Lebens-Lauff).

His movements have great

rhythmic variety, including

patterns borrowed from the polonoises

and mazurkas of the

Polish and Moravian folk

musicians he heard in Cracow

and Upper Silesia in 1705-6

which he “dressed in an

Italian coat” (Selbstbiographie)

[1/IV, 2/II, 3/IV, 4/I].

Contrapuntally he is more

conservative; for him, as

for the composers of the

early Baroque, the trio

sonata “provided an ideal

meeting point between the

older, stricter polyphony

and the new emphasis on

accompanied melody”

(Newman). Again we suspect

the influence of Corelli.

Telemann in fact blends a

surprising amount of

counterpoint, by then

unfashionable, into his trio

sonatas. 2/II, for example

(in a trio taken from a

collection Telemann

described as “written in a

more sober mood”) is a full

fugue; and looser fugal

movements, enlivened by the

“pleasing and brilliant”

episodes recommended for

such occasions by Quantz,

are to be found, for

example, in 3/II and 4/I

& III. Imitations of

both long and short phrases

abound.

Almost throughout we find the

equality of the upper parts

that Telemann reports having

been admired by his

contemporaries. But the

occasional movement

consisting of a melody in

one part simply accompanied

by the other part furnishes

an interesting change of

texture [1/IV & VII,

2/I]. He inventively keeps

to a minimum those passages

in thirds and sixths which,

although “one of the

ornaments of a trio” his

contemporaries sometimes

”abused or dragged on ad

nauseam” (Quantz). As Quantz

recommends, he “regularly

interrupted” them “with

passagework or other

imitations” [1/III, 5/II-IV,

9/I & III].

In form he drew elements

from both the sonata da

chiesa (church sonata)

which consisted of (usually)

four purely abstract

movements of a serious

character, and the sonata

da camera (court

sonata) which consisted more

of dance movements in a

lighter vein. [1] is close

to the sonata da camera,

having no fewer than eight

movements, including an

Italianate French Overture

(I & II) and a “hunting”

gigue (VII). But normally

Telemann writes a

four-movement form with a

lighter last movement,

presumably to revive

flagging attention, often

derived from the dance

(Menuet with unaccompanied

Trio section in the parallel

major, 2/IV; Gavotte with

“brilliant” episodes, 3/IV;

Passepied, 9/IV).

To sum up, “the strengths of

Telemann’s sonatas lie in

their fluent crafismanship,

clear lines, compelling

harmony, effective writing

for the instruments, and

satisfying structural

organisation” (Newman).

|

|

|

|