|

|

1 LP -

1C 067-16 9528 1 - (p) 1985

|

|

| 1 CD -

567-16 9528 2 - (p) 1985 |

|

| 1 CD -

GD 77014 - (c) 1990 |

|

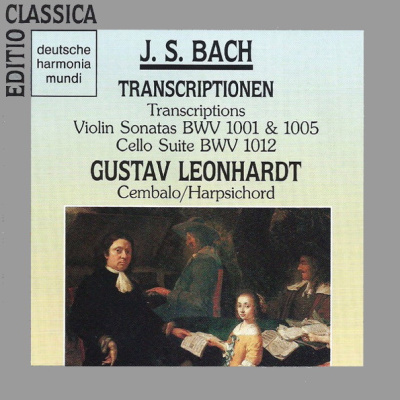

TRANSCRIPTIONEN

BEARBEITET VON GUSTAV LEONHARDT

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Sonate

d-moll - nach der Sonate Nr. 1

g-moll, BWV 1001, für Violine solo für

Cembalo |

|

13' 28" |

|

|

- Adagio

|

3' 21" |

|

A1 |

|

- Fuga.

Allegro

|

5' 00" |

|

A2 |

|

- Siciliano

|

3' 13" |

|

A3 |

|

- Presto |

1' 54" |

|

A4 |

|

Sonate

G-dur - nach der Sonate Nr. 3 C-dur,

BWV 1005, für Violine solo für Cembalo |

|

17' 16" |

|

|

- Adagio

|

3' 19" |

|

A5 |

|

- Fuga. Alla

breve

|

7' 59" |

|

A6 |

|

- Largo |

3' 18" |

|

B1 |

|

- Allergo assai |

2' 40" |

|

B2 |

|

Suite

D-dur - nach der Suite Nr. 6 D-dur,

BWV 1012, für Viola pomposa für Cembalo |

|

16' 47" |

|

|

- Prélude |

3' 34" |

|

B3 |

|

- Allemande |

3' 55" |

|

B4 |

|

- Courante |

1' 38" |

|

B5 |

|

- Sarabande |

2' 39" |

|

B6 |

|

- Gavotte I/II |

3' 12" |

|

B7 |

|

- Gigue |

1' 49" |

|

B8 |

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav LEONHARDT,

Cembalo (Nicholas Lefebvre, Rouen

1755; restauriert von Martin

Skowroneck, Bremen, 1984)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Doopsgezinde Gemeente

Kerk, Haarlem (Holland) - 1985

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Dr. Thomas Gallia |

Klaus L Neumann | Benjamin

Bernfeld

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Sonart, Milano /

harmonia mundi acustica

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Harmonia Mundi (EMI

Electrola) | 1C 067-16 9528 1 | 1

LP - durata 47' 53" | (p) 1985 |

DIGITAL

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Harmonia Mundi | LC 0761 |

567 16 8528 2

| 1 CD -

durata 47' 53"

| (9) 1985 |

DDD

Deutsche

Harmonia Mundi | LC

0761 | GD 77014 | 1

CD - durata 47' 53"

| (c) 1995 | DDD

|

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

Familienbild. Gemälde

von Gillis van Tilborgh um

1625-1678. Mit freundlicher

Genehmigung des

Wallraf-Richartz-Museums, Köln.

|

|

|

Note |

|

Eine Coproduktion mit

dem WDR Köln. |

|

|

|

|

We tend

nowadays to view

arrangements of old music

somewhat sceptically, bieng

in general of the opinion

that one should respect the

form in which a work of art

was created. Such a maxim is

easy enough to follow when

applied to literature of the

fine arts: no one would

seriously have the audacity

these days to re-touch an

old master or to tamper with

the text of a great author.

As regards music, however,

the problem takes a somewhat

different shape: a piece of

music can be said fully to

exist only in this or that

performance, but each

performance, at the same

time, unavoidably adapts the

work in some way to the

present. The modern practice

of so-called "historical

performances" is an effort

to reduce this effect; by

attempting to reconstruct

the instruments and

performing practices of the

period in which older works

were composed, the

performers hope to achieve

the "original sound".

It might strike one as

paradoxial that this very

school of thought should

itself produce an

arrangement of a piece of

old music. In fact, however,

careful consideration shows

that it is completely

consistent with the attempt

to take the historical

presuppositions of a work

into account. The history of

music shows that our modern

view of the relation between

the musical text and its

interpretations or between

the original and its

arrangements or adaptations

is itself historically

conditioned and cannot

simply be applied

uncritically to the music of

other epochs. For example,

in order to perform the

thoroughbass or the

ornaments in a Baroque

composition one must not

only be versed in the

historical rules but must

also be a good improviser.

And often enough the sources

for a composition from the

17th or early 18th century

are such that a modern

editor will find it

impossible to say exactly

what the original version of

the work was. Experiences

such as these have led us to

realize that the full

dimensions of a Baroque

composition are not revealed

in any single version, no

matter how "original", nor

in any single

interpretation, no matter

how true to the work and

historically accurate - an

insight whose historical

relevance is documented by

the numerous arrangements

which Bach made of both his

own works and those of

others and which Bach's

contemporaries made of this

compositions,

The idea of making new

arrangements of Bach's works

did not, however, originate

with the relatively recent

historical movement. As

early as the 19th century,

there were numerous attempts

to "improve upon" or

"enrich" his compositions,

especially the sonatas and

partitas for solo violin.

The arrangers of that period

were, however, allowed

liberies which would be

unthinkable nowadays, as is

made quite clear by the

review of the "selected

Works from the solo violin

sonatas, arranged for

pianoforte by Joachim Raff"

which was published in 1869

in the "Allgemeine

musikalische Zeitung" in

Leipzig. The reviewer

remarks how the

accompaniment "heightens and

adorns" Bach's motives and

points out the "figures and

motives" added at places

which "Bach had intended to

be polyphonic but which are

not completely polyphonic

due to the limitations of

the instrument".

Nonetheless, at some points

the reviewer does exhibit

scruples about Raff's

methods. Having already

commented at the beginning

of his article that a

previously published

arrangement of the chaconne

from the 2nd partita betrays

an over-powerful urge to

turns this composition into

a brilliant piano piece

along modern lines, he notes

reproachfully: "One could

point out several individual

passages which are written

more in the modern way than

in Bach's style." It is

characteristic of our

modern-day approach to the

art of bygone eras that a

contemporary arrangement

should take as its model the

practices of Bach's own

period rather than

perpetuating this

19th-century tradition. This

model is clearly illustrated

here by the harpsichord

version of the first

movement of the third sonata

(BWV 1005), arranged by one

of Bach's contemporaries who

was a member of his own

circle. Comparing this

arrangement with the

original, we see that the

differences between the two

are essentially attributable

to the different tonal

properties of the

instruments. The

transposition, doubling and

augmenting of the intervals

between the parts are

related to the greater tonal

range of the harpsichord; on

th other hand, the fact that

long note-values are split

up into shorter ones, that

the chords are more dense

and that arpeggios are used

to bolster the harmonies are

due to the more limited

capacity of the keyboard

instrument for holding,

intensifying and modulating

the tone.

The problems posed by the

other movements differ in

accordance with the

character of the movement in

question: when transferring

a fugue, for example, from

the violin to the

harpsichord, the parts must

be elaborated; in a slow

movement, the harpsichord

version requires additional

contrapuntal and chordal

elements in ordder to

maintain the same density of

sound; and in fast

movements, changes in the

register and the chording of

the melody as well as

harmonic supporting material

provide that structural

orientation which the violin

can create by means of

dynamics and accentuation.

In what way, we may ask in

concluding, do these

arrangements reveal new

dimensions of Bach's work?

Most importantly, they

transcend the specific

limitations and qualities of

an individual instrument,

thus laying bare the musical

substance. At first glance,

it might seem impossible

that a given composition

should be capable of

bridging the differences

between the musical

presuppositions inherent in

the violin and the

harpsichord. Tha fact that

these works show it to be

possible after all is sue in

part to the adaptability of

musical compositions in the

Baroque period and in part

to the extraordinary quality

of Bach's art.

Kurt

Deggeller

|

|

|

|