|

|

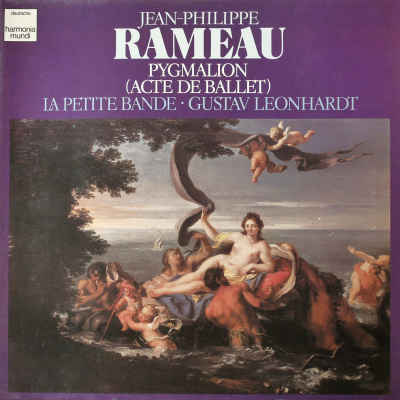

1 LP -

1C 065-99 914 - (p) 1981

|

|

| 1 CD -

GD 77143 - (c) 1990 |

|

PYGMALION

(1748) - Acte de Ballet. Text von Ballot

de Sovot, nach Houdard de la Motte

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jean-Philippe

RAMEAU (1683-1764) |

Pygmalion,

1748

|

|

|

|

|

- Ouverture

|

|

5' 18" |

A1 |

|

- Scène 1 -

Pygmalion: "Fatal Amour,

cruel vainqueur"

|

|

3' 40" |

A2 |

|

- Scène 2 -

Céphise: "Pygmalion, est il

possible" |

|

2' 43" |

A3 |

|

- Scène 3 - Pygmalion: "Que

d'appas! que

d'attrais!" |

|

4' 46" |

A4 |

|

-

Scène 3 - La Statue: "Que vois-je? Où

suis-je?"

|

|

3' 41" |

A5 |

|

- Scène 4 - L'Amour: "Du pouvoir

de l'Amour"

|

|

3' 44" |

A7 |

|

- Scène 4 -

Air

|

|

0' 33" |

A8 |

|

- Scène 4 - Gavotte gracieuse

|

|

0' 12" |

A9 |

|

- Scène 4 -

Menuet |

|

0' 29" |

A10 |

|

- Scène 4

- Gavotte gaie

|

|

0' 15" |

A11 |

|

- Scène 4 -

Chaconne vive

|

|

0' 23" |

A12 |

|

- Scène 4 - Loure très grave

|

|

0' 30" |

A13 |

|

- Scène 4 - Les Grâces

(Passepied

vif) |

|

0' 22" |

A14 |

|

- Scène 4 - Rigaudon, Vif |

|

0' 30" |

A15 |

|

- Scène 4 - Sarabande pour la

Statue

|

|

2' 44" |

B1 |

|

- Scène 4 - Tambourin. Fort et

vite |

|

1' 00" |

B2 |

|

- Scène 4 - Chœur de Peuple:

"Cédons à

notr'impatience"

|

|

0' 11" |

B3 |

|

- Scène 4 - Pygmalion: "Le peuple

dans ces

lieux"

|

|

0' 27" |

B4 |

|

- Scène 5 - Chœur: "L'Amour

triomphe" |

|

4' 44" |

B5 |

|

- Scène 5 - Pantomine niaise

et un peu

lente |

|

3' 37" |

B6 |

|

- Scène 5 - Pygmalion: "Règne,

Amour" |

|

5' 05" |

B7 |

|

- Scène 5 - Air |

|

0' 51" |

B8 |

|

- Scène 5 - Rondeau

Contredanse.

Gai

|

|

1' 35" |

B9 |

|

|

|

|

|

John Elwes, Tenor

(Pygmalion)

Mieke van der Sluis, Sopran

(Céphise)

François Vanhecke, Sopran

(Statue)

Rachel Yakar, Sopran

(Amour)

Continuo:

Bob van Asperen, Cembalo

Richte van der Meer, Violoncello

|

CHŒUR DE LA

CHAPELLE ROYALE, PARIS / Philippe

Herreweghe, Einstudierung

LA PETITE BANDE / Sigiswald

Kuijken, Konzertmeister

/ Gustav LEONHARDT, Leitung

- Sigiswald Kuijken, Alda

Stuurop, François Fernandez, Mihoko

Kimura, Marie Leonhardt, 1.

Violine

- Janneke van der Meer, Dirk

Verelst, Keiko Watanabe, Janine

Rubinlicht, Nicolette Moonen, 2.

Violine

- Richard Walz, Ruth Hesseling,

Staas Swierstra, Marinette Troost, Viola

- Richte van der Meer, Wouter

Möller, Lidewij Scheifes, Violoncello

- Anthony Woodrow, Nicholas Pap, Kontrabaß

- Barthold Kuijken, Robert Claire, Flöte

- Bruce Haynes, Ku Ebbinge, Pol

Dombrecht, Pieter Dhont, Oboe

- Danny Bond, Claude Wassmer, Fagott

- Bob van Asperen, Cembalo

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Doopsgezinde Gemeente

Kerk, Haarlem (Holland) - 1/5

ottobre 1980

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Klaus L. Neumann |

Barbara Valentin | Dr. Thomas

Gallia | Paul Dery | Monica Werner

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Sonart, Milano

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Harmonia Mundi (EMI

Electrola) | 1C 065-99 914 | 1 LP

- durata 47' 22" | (p) 1981

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Harmonia Mundi | LC 0761 |

GD 77143 | 1 CD - durata 47'

22" | (c) 1990 | ADD

|

|

|

Cover Art

|

|

"Der Triumph der

Galatea". Gemälde von Giuseppe B.

Chiari (1654-1727). Mit Freundl.

Genehmigung von der Gemäldegalerie

Alte Meister, Schloß Wilhelmshöhe,

Kassel.

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

Jean-Philippe

Rameau is one of the most

important figures in

European music history, both

as a composer and as a

theorist. He was born two

years earlier than Bach and

Handel and was the son of an

organist. After a short stay

in Italy he made a meager

living as a poorly paid

violinist in theater

orchestras before becoming

an organist himself. He,

however, did not manage to

get out of the provinces as

he lacked the necessary

connections to the capital.

He first attracted attention

when 39 years old with his

work of lasting importance,

Traité de l'harmonie,

réduit à ses principes

naturels. In this

treatise he described the

sixth and six-four chords as

inversions of a triad,

overturned the prevailing

conception of the “equality

of the seven scale degrees”,

and founded the functional

and cadential harmonic

theory which was valid until

the end of the 19th century.

It is astonishing that this

“Newton of Music" was 50

years old - even older than

Bruckner - before he became

successful. He first had to

spend ten quiet years as an

organist in Paris, where he,

among other things,

furnished music for

vaudeville theater comedies

before devoting his

attention to the composition

of operas in 1733. A

student, the wife of a

powerful land-owner and

patron, La Pouplinière,

interceded in behalf of the

performance of his first

opera, Hippolyte et

Aricie (1733). After

this Rameau was regarded as

a “new Lully" and was given

many decorations and

important jobs (composer of

chamber music for Louis XV).

His abilities as a

harpsichordist, in addition

to those as a theorist, were

now also discovered. By

imitating noises and

movements in a naturalistic

way, he revealed sound

colours new to the

harpsichord. It was

recognized that he had

striven for a unified

artistic whole -

pre-Wagnerian from a modern

point of view - in his

compositions for the

theater.

He skillfully combined the

French preference for ballet

and the form of

“sprechgesang" developed by

Lully with harmonic and

instrumental innovations. He

also did not follow the

Italian style in his

recitatives, with its free

and cantabile declamation

supported by chords from the

harpsichord. He instead let

himself be guided by the

strict rhythmical form of

the stately language, which

was usually in alexandrines.

He invented a system of

notation with many changes

of meter which could be

adapted to the musical

rhythm of the language. The

aria emerges unnoticeably

from the recitative and is

felt to be an

intensification and

enhancement of it.

The balance between the

vocal and instrumental music

and dance, which was typical

for the French opera, may

also be found in Pygmalion,

the first of the eight

one-act ballets that Rameau

wrote between 1748 and 1754.

The libretto was written by

Ballot de Sovot (or Sauvot),

a member of La Pouplinière’s

circle. It, as usual, is

based on a myth (G. B. Shaw

used the same material in

his drama of the same name).

Ballot de Sovot took it from

the tenth book (line 234ff)

of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

It relates the story of a

sculptor who, disillusioned

by women, carves himself a

statue out of ivory of an

ideal woman. He falls in

love with it and, at a

festival for Aphrodite, asks

the goddess to give him a

wife like his work of art.

When at home he again

embraces his statue and it

quickens and becomes

animate, awakens and joins

itself with him, bearing him

a child after nine months.

This act, which Ovid himself

described as “abominable

love", was toned down in

Rameau’s version because it

was considered to be

improper at that time. Amor,

unnoticed by the

passionately lamenting

Pygmalion, brings the statue

to life with a torch. The

Graces then enter and

perform a series of dances

with which the drama is

transformed into a ballet.

As the dances gradually

become more extensive, Air,

Gavotte, Menuett,

Chaconne, Loure,

Passepied, and Rigaudon,

the statue is still very

unsure of itself. She,

however, takes the

initiative in the Sarabande

and Tambourin. This

is reason enough for the

chorus to strike up a hymn

to the god Amor, and to

honour him in a second Divertissement.

The abundance of musical

details worthy of note can

only be hinted at here. The

Ouverture, following

its slow introduction,

portrays the sculptor

“carving” with his knife

with its quick repeated

notes and bold use of the

woodwinds. As the opera

unfolds the falling seventh

sung by the lamenting

Pygmalion almost gains the

significance of a

“leitmotiv”. In his entreaty

to Venus the shift from pain

to hope is emphasized by the

simple means of a

corresponding change from G

minor to G major. As the Symphonie

tendre et harmonieuse

with its element of the

fantastic is played and the

theater becomes lighter, the

statue comes to life. The

bright E major tonal center

of the Symphonie

stands in direct contrast to

the preceding “worldly”

atmosphere. It is striking

that - with the exception of

the Ouverture which

is notated in eight parts -

large sections of the score

only contain two or three

instrumental parts.

Previously it was believed

that Rameau could not have

intended such a “thin”

texture and the “missing”

parts were added. We,

however, having studied the

question thoroughly, are of

the opinion that each

measure of the score reflects

Rameau’s intentions.

©

Uwe Kraemer, 1981

SYNOPSIS OF THE TEXT

Pygmalion, by

Jean-Philippe Rameau, is a

ballet in five scenes for a

tenor (Pygmalion), three

sopranos (Céphise, Statue

and Amor), and chorus (the

Graces, the common people).

In the first scene Pygmalion

accuses Amor of being a

mischievous god, a conqueror

who punishes wickedly and

whose power he is afraid of.

He has fallen in love with

the statue representing love

which he himself has carved.

He cannot expect it to

return his feelings. Amor

becomes a witness to the

passion which has

overwhelmed Pygmalion, who

can barely believe that he

himself made the statue. Had

he, with his artistic

ability, created a statue

worthy of idolization simply

in order that he be

tormented by unrequitable

love?

The second scene consists of

a dialogue in song between

Pygmalion and Céphise, his

love. Céphise complains of

his coldness towards her,

the one who loves him. Had

this object, this statue,

taken away his tender

feelings towards her?

Pygmalion explains that his

confusion is caused by a god

who is revenging himself for

the defiance Pygmalion once

showed towards him. Céphise

regards this as an attempt

to conceal a love which she

is insulted by. He finally

admits to her that he loves

the statue passionately.

She, however, does not

believe him. He swears that

heaven’s rage has brought

him into this desperate

situation. She recognizes

that she has lost him and

prays that the just gods may

punish him.

The third scene begins with

a monologue in praise of the

statue. In it Pygmalion

first speaks of his

confusion and begs Venus,

the mother of passions, to

still the desire within his

breast. He attributes the

statue, which has captured

his heart, to Amor, the son

of Venus. Finally, he asks

if the gods were not

supposed to be the

charitable protectors of

mankind. Then the statue

comes to life and is

immediately filled with love

for the person she sees in

front of herself. She

recognizes her own feelings

in his eyes. Her only wish

is to please and obey him:

The only thing she knows

about herself is that she

idolizes him.

In the fourth scene Amor

explains that he was

responsible for this

miracle, but that only an

excellent sculptor like

Pygmalion could have created

such a statue. He promises

him eternal happiness as a

reward for his artistic

ability. Amor calls in the

Graces to proclaim the power

of love to the world.

In the last scene Pygmalion

extols the victory of love

to the common people. The

chorus of the Graces and

common people answers with

the same words. It ends with

Pygmalion singing a song of

praise to Amor who, with his

divine fire, had brought the

object of his love to life.

|

|

|

|