|

|

1 LP -

20 22618-2 - (p) 1975

|

|

| 2 CDs -

74321 32320 2 - (c) 1995 |

|

PARTIEN FÜR

CEMBALO - FASSUNGEN VON GUSTAV LEONHARDT

NACH DEN WERKEN FÜR VIOLINE SOLO

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

BACH (1685-1750) |

Partia

in A-dur für Cembalo - nach der Violinsolopartia in E-dur,

BWV 1006 |

|

15' 05" |

|

|

- Preludio

|

3' 59" |

|

A1 |

|

- Loure

|

3' 09" |

|

A2 |

|

- Gavotte en

Rondeau |

3' 00" |

|

A3 |

|

- Menuet |

3' 09" |

|

A4 |

|

- Bourrée |

0' 47" |

|

A5 |

|

- Gigue |

1' 01" |

|

A6 |

|

Partia

in g-moll für Cembalo - nach der Violinsolopartia in

d-moll, BWV 1004 |

|

21' 53" |

|

|

- Allemanda |

2' 47" |

|

A7 |

|

- Corrente

|

1' 23" |

|

A8 |

|

- Sarabanda

|

3' 30" |

|

A9 |

|

- Giga |

2'

00"

|

|

A10 |

|

- Ciaccona |

12' 13" |

|

B1 |

|

Partia

in e-moll für Cembalo - nach der Violinsolopartia in

h-moll, BWV 1002 |

|

15' 30" |

|

|

- Allemande

· Double

|

4' 52" |

|

B2 |

|

- Courante ·

Double

|

3' 42" |

|

B3 |

|

- Sarabande

· Double

|

3' 54" |

|

B4 |

|

- Tempo di

Borea · Double |

3' 02" |

|

B5 |

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav LEONHARDT,

Cembalo (William Dowd, Paris

1975, nach Blanchet, Paris um

1730)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Cedernsaal, Schloß

Kirchheim (Germany) - giugno 1975

|

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Dr. Thomas Gallia |

Paul Dery

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Sonart, Milano

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Harmonia Mundi (Basf)

| 20 22618-2 | 1 LP - durata 52'

28" | (p) 1975

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Harmonia Mundi | LC 0761 |

74321 32320 2 | 2 CDs -

durata 51' 11" - 60' 08" |

(c) 1995 | ADD/DDD

|

|

|

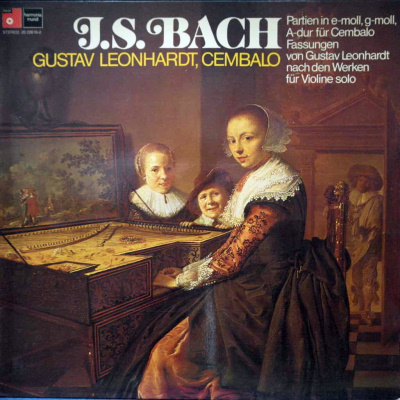

Cover Art

|

|

"Frau am Cembalo" by

Jan Miense Molenaer (1609-1668).

|

|

|

Note |

|

L'edizione in doppio

CD contiene anche la pubblicazione

del 1985 (1C 067-16 9525 1) ed il

Preludio, Fuga e Allegro BWV 998

contenuto nella pubblicazione (HMS

30 868) del 1968. |

|

|

|

|

The keyboard

player has always had the

pleasure of being to play by

himself what others have to

form an ensemble to play.

And this is not only his

pleasure but also his gride.

And so, in addition to

"original" pieces, the

history of music is filled

with a host of

"arrangements": theyy range

from transcriptions of

popular vocal and

instrumental pieces in the

sixteenth century to piano

scores of symphonies and

operas in the ninetenth.

When, as was often the case,

a great composer turned his

hand to making an

arrangement, the result was

a real keyboard work in its

own right - indeed, a

composer was not

infrequently his own

arranger (Byrd, Bach,

Stravinsky, etc.)! What

makes all these arrangements

enjoyable even today is the

undisturbed stylistic

relationship

between the original

and the arrangement. Many

people are finding that the

only arrangements which are

not enjoyable are those

whose idiom or sound is

alien.

In his earlier years, Bach

set concerti by his

contemporaries Vivaldi,

Johann Ernst von

Sachsen-Weimar, Marcello and

Telemann for a keyboard

instrument, and in later

years he released his own

exorbitantly difficult works

for solo violin from their

isolation by transferring

them - in either improvised

or notated form - to the

keyboard.

His pupil Agricola reports

as late as 1773: "Their

author himself played them

frequently on the

clavichord, and added as

much harmony to them as he

found mecessary". And Adlung

observed in 1758: "[3

sonatas and 3 partitas]

however are very suitable

for playing on the clavier".

Nowadays we have the

complete A minor sonata in a

keyboard version in his hand

(at least I see non reason

for believing that

thoroughly Bachian piece to

have been the work of a

pupil). The organ version of

the G minor fugue (complete

with a new Praeludium) could

similarly be his own work

the bold arrangement of the

first movement of the C

major sonata should probably

be asribed to one of his

pupils (it may perhaps be

the work of Altnikol), while

the E major partita survives

in a keyboard version made

by a somewhat indifferent

player. Bach himself

arranged the first movement

of this work as the

introduction to Cantata No.

29 for organ obbligato with

accompanying trumpets,

timpani, oboes an strings.

And how much more may have

been lost?

I think that Bach would have

forgiven me for the fact

that I have set myself to

making arrangements of his

works; whether he would have

forgiven the way in which I

have done it, remains of

cours a moot point. There is

at least a strong incentive

in putting oneself to the

test with the question of

how far it is possible int a

twentieth-century player to

put himself back in thought

and freeling into Bach's

keyboard style.

The deeper stimules to make

these arrangements, of

course, lies in the unique

beauty of those works which

we hear on the violin only

too infrequently.

I added only "such harmony

as was necessary" and hope,

with the harpsichord sound

with which Bach was

familiar, to have matched

his idiom in such a way that

no alien feeling is

apparent.

The transposition downwards

by a fith (or a fourth)

corresponds to Bach's own

practice; in this way, the

harpsichord keybiard's

compass (GG-d") is fully and

naturally exploited.

Gustav

Leonhardt

|

|

|

|