|

1 LP -

(p) 1965

CRM 510 Mono - CRS 1510 Stereo

|

|

| 1 CD -

PA0019 - (p) 2022 |

|

Organ Music of

Elizabethan England

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| John MUNDAY (c.1560-1630) |

Robin

(FVB I, 66) |

organo |

|

2' 09" |

A1 |

| Giles FARNABY (c.1560-1640)

|

Loth

to Depart (FVB II, 317) |

organo |

|

3' 39" |

A2

|

|

Fantasia (FVB II, 270) |

organo |

|

3' 53" |

A3

|

| John BULL (c.1562-1628) |

Gloria

Tibi Trinitas (FVB I, 160) |

organo |

|

3' 51" |

A4 |

| Peter PHILIPS (1560/61-1628) |

Fantasia

(FVB I, 335) |

organo |

|

11' 10" |

A5 |

| Orlando GIBBONS (1583-1625) |

Fantasia

(MB XX, 7) |

organo |

|

1' 35" |

B1 |

|

Prelude

(MB XX, 6) |

organo |

|

0' 59" |

B2 |

|

Fantasia

(MB XX, 11) |

organo |

|

4' 41" |

B3 |

| Thomas TOMKINS (1572-1656) |

Ground

(MB V, 93) |

organo |

|

5' 16" |

B4 |

| William BYRD (1543-1623) |

Miserere

(FVB II, 232) |

organo |

|

3' 21" |

B5 |

|

Fantasia

(FVB II, 406) |

organo |

|

8' 00" |

B6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

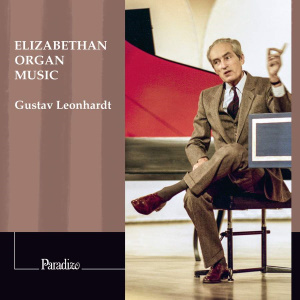

Gustav

Leonhardt, organ (Schnitger in

Michaelskerk, Zwolle, Holland)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Michaelskerk, Zwolle

(Olanda) - 1962

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Direction

artistic |

|

- |

|

|

Recording

Engineer

|

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Cambridge Records |

CRM 510 Mono - CRS 1510 Stereo | 1

LP - durata 48' 34" | (p) 1965 |

ANA

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Paadizo | PA0019 | 1

CD - durata 48' 34" | (p) 2022 |

ADD |

|

|

Cover

|

|

-

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Elizabethan

Organ Music played by

Gustav Leonhardt

The

mention of “Elizabethan

England” brings forth images

of an era of great artistic

productivity and of a

society dominated by heroic

individuals. The list of the

prominent ones must begin

with the Queen herself and

would continue with William

Shakespeare, Sir Francis

Drake, Sir Walter Raleigh,

Sir Philip Sidney,

Christopher Marlowe, Sir

Francis Bacon, and many

others. Some are known for

their heroic adventures,

some for the grandeur or

even the extravagance of

their personal life-styles,

and some for their

masterpieces of literature.

The reign of Elizabeth

(1558-1603) also witnessed

the apex of music for the

virginals - by which was

meant any type of

harpsichord but especially

the oblong instrument so

often painted by Vermeer in

particular. The virginals

had been favored by Henry

VIII, himself a skilled

performer.

Some of the music within

this great flowering - known

as the “English virginalist

school”- is, however,

optionally and even

idiomatically for organ.

This is suggested by the

titles of some pieces and by

the texture and writing of

others. Gustav Leonhardt

chose this program

accordingly, and undertook

to record it on the famous

organ at Zwolle, not because

of its size but rather for

its appropriate sounds and

the renaissance acoustical

atmosphere of the church.

The

Composers

The

most famous of the composers

represented here is

undoubtedly William Byrd

(1543-1623). Byrd was a

master of virtually every

major genre of music of his

day: madrigal and solo song,

church music for both his

own Roman Catholic church as

well as for the Church of

England, chamber music for a

variety of “consorts,” and

keyboard music. An

evaluation of Byrd by a

contemporary in 1586, quoted

by Edmund Fellowes in his

biography of the composer,

acknowledges Byrd as “the

most celebrated musician and

organist of the English

nation who was held in the

highest estimation.” In 1575

Queen Elizabeth granted Byrd

and his teacher Thomas

Tallis a monopoly for

printed music and music

paper - the first copyright

in England. Unlike Sir

Walter Raleigh, who made a

fortune from his monopoly on

the sale of wine, Byrd and

Tallis did not make even a

modest profit. But Byrd, who

was constantly in lawsuits

as a result of his real

estate dealings, seems to

have tried to take advantage

of the copyright; one

complaint reads that “One

Byrde, a Singing man, hathe

a licence for printinge of

all Musicke bookes

and by that meanes he

claimeth the printing of ruled

paper." As a musician

Byrd was organist at Lincoln

Cathedral from 1563 until

1572, and from 1570 was a

member of the Chapel Royal -

the musical establishment

“on call” to the royal

household. His favor with

the Queen seems remarkable,

and attests to his

greatness, since he never

converted from his Roman

Catholicism.

While Byrd stands alone in

his generation, the next had

several prominent composers,

most of whom are represented

here. The virtuoso of the

era was John Bull, often

referred to as Dr. Bull (c.

1562-1628). Due to his fame

throughout Europe for his

ability to dazzle crowds

with technical virtuosity,

music historians today refer

to him as the “Liszt of his

Age." The title of “Doctor”

was conferred upon him at

Cambridge in 1592; he had

received the Mus. Bac. at

Oxford in 1586, “having

practised in that faculty

fourteen years.” By 1585,

Bull had joined the Chapel

Royal where he became

organist in 1591. He left

England in 1613 and by at

least 1617 had become the

organist at the Roman

Catholic Cathedral in

Antwerp, where he died

eleven years later. Through

his performances in the Low

Countries, his music

provided a link from the

English Virginalist School

to the famed Dutch master J.

P. Sweelinck, who taught the

English style of keyboard

figuration to generations of

North German organists.

On the same day that Bull

was awarded his doctorate,

Giles Farnaby (c. 1560-1640)

was receiving the B. Mus. at

Oxford. Little else is known

of the career of Farnaby,

but, like Bull's, his fame

is for his keyboard music.

Because he did not compose

in other genres (such as

choral music) and because he

was not famous as a virtuoso

performer, Farnaby has

suffered undue neglect and

he is only recently becoming

better known to modern

audiences. Many writers

judge his keyboard

composition as second only

to that of William Byrd.

Another composer who worked

principally in keyboard

music is John Munday or

Mundy (c. 1560-1630). Munday

was awarded the B. Mus. at

Oxford in 1586 and the D.

Mus. in 1624. He was

organist at Eton College and

after about 1585 at St.

George's Chapel, Windsor.

Peter Philips (1560 or

1561-1628) was, like Byrd

and Bull, a Roman Catholic

and probably began his

musical career as a

chorister at St. Paul's

Cathedral in London. While

in his very early twenties

he inherited enough money to

travel extensively on the

Continent. In 1585, while in

Rome in the service of

Cardinal Alessandre Farnese,

he joined the household of

Lord Thomas Paget and

traveled with him through

Spain, France, and the

Netherlands. From early 1587

through June of 1588 they

were in Paris, and by 1589

in Antwerp. Lord Paget died

in 1590 but the story does

not end there. Philips spent

the remainder of his life

mostly in Antwerp, but made

a trip to Amsterdam in 1593

where he met Sweelinck.

Returning from this visit he

was arrested in Middelburgh

and charged with planning

the assassination of Queen

Elizabeth, and alleged to

have participated with Lord

Paget in the act of burning

the Queen in effigy in

Paris. The case was brought

to trial in September, 1593

but he was released for lack

of evidence.

In the third generation of

composers represented in

this recording are Orlando

Gibbons (1583-1625) and

Thomas Tomkins (1572-l656).

Gibbons is endeared to

madrigal singers by his

famous “The Silver Swan” and

other highly polished gems

but he is perhaps more

important for his church

music. In this and other

regards he can be compared

with J. S. Bach, who

followed him by nearly a

century. Both stood at the

end of brilliant eras - the

Elizabethan in England, and

the Baroque in Germany. Both

stand unexcelled in the

genres in which they worked.

Both represent the highest

in inspirational and

artistic integrity, which

accounts for their continued

popularity in the Sunday

services of Anglicans and

Lutherans today - and in

other churches and concert

halls as well. And both were

members of prominent musical

families. From 1605 Gibbons

was a member of the Chapel

Royal and in 1619 was listed

as one of his majesty's

“musicians for the

virginalles to attend in his

highness privie chamber.” He

was also famous as one of

the finest organists of his

time.

Thomas Tomkins, like

Gibbons, was part of an

important musical family. He

was a pupil of William Byrd

and was granted the Mus. B.

at Oxford in 1607 at the age

of thirty-five - “after

fourteen years a student.”

He was an organist of the

Chapel Royal in 1621 but his

most important position was

as organist at Worcester

Cathedral, which post he

held from about 1596 (the

year before he married the

widow of his predecessor)

until 1646. As pointed out

by Denis Stevens in his

biography of Tomkins, the

composer was very much a

part of the Elizabethan

“school” of composers

although he outlived the

others by decades and

continued writing in the old

style even as fashions were

changing markedly during his

mature and later years.

The

Musical Sources

While

all of the music on these

records is available in

print today, none was

printed when it was

composed. In fact there was

very little keyboard music

published in England at the

time. Only two small

collections (Parthenia

and Parthenia In-violata)

appeared in print, both in

the 1610's. At a time when

music printing flourished

for vocal music, it seems

strange that only a few

dozen keyboard pieces

appeared in print out of the

hundreds that survive in

manuscript or hand-written

copies. The majority of the

works on this recording can

be found in a famous

manuscript collection, The

Fitzwilliam Virginal Book,

now available in an

inexpensive two-volume

paperback edition. The

abbreviation FVB below

refers to this source, with

appropriate volume and page

numbers. This collection is

named for the museum housing

it and contains about three

hundred works - almost one

half the total number of

keyboard works surviving

from the English Virginalist

School. It was copied out,

by Francis Tregian (d.

1619), apparently while he

was in prison for

politico-religious reasons.

Other virginal books and

manuscripts are mentioned

below in those cases where a

different source was used

for the performance. Music

not in The Fitzwilliam

Virginal Book can be

found easily in the

scholarly editions of the

keyboard works of individual

composers in the Musica

Britannica series

(abbreviated MB below and

followed by appropriate

volume and page numbers);

the music of Tomkins was

edited by Stephen Tuttle,

Gibbons by Gerald Hendrie,

and Bull by Thurston Dart.

The

Music

Side

A - “Robin” refers to

none other than the very

Robin chased about by the

Sheriff of Nottingham. The

song upon which this set of

varìations is based is

sometimes referred to by the

titles “My Robin is to the

Greenwood Gone” or “Robin

Hood is to the Greenwood

Gone.” Giles Farnaby and

William Byrd also wrote

variations on this lovely

song and called their works

“Bonny Sweet Robin;” from

this we can possibly learn

one line of the tune (none

are known for sure) since

Shakespeare's Ophelia sings

the line in Hamlet “for

bonny sweet Robin is all my

joy.” The sweet pastoral and

melancholy mood that this

line might suggest is also

present in the graceful

melody and in Munday's

lightly frolicking

varìations.

“Loth am I to depart; O

Music, sound my doleful

plaints when I am gone away”

says Damon as he departs in

the old Damon and

Pithias. The “Loth to

Depart” is referred to in

several contemporary plays

and was customarily

performed when friends took

leave of one another. In his

variations on the song,

Farnaby avoids any

contrapuntal complexities

and uses simple ornamental

figuration - for the

invention of which he is

particularly famous. What a

contrast the reserved

variations of Farnaby

provide to the pastoral set

of variations by Munday -

but both more than likely

quite in keeping with the

mood of the original songs.

Farnaby is represented in The

Fitzwilliam Virginal Book

by no fewer than ten

fantasias - more than any

other composer. According to

Willi Apel this fantasia is

“the most unified and on the

whole successful fantasy” of

the group; after the lively

opening rhythmic section,

echo effects, inherent in

the music itself, are

further brought out in this

performance on the organ.

To understand Bull`s “Gloria

Tibi Trinitas” it is

necessary to understand the

concept of a cantus

firmus, literally

fixed song. Just as

Shakespeare was wont to take

a basic plot from another

source and then imbue it

with his own elaborations

and character development,

many Renaissance composers

chose to take a song (or

chant, or perhaps an

invented melody) and set

this in relatively long

notes while weaving more

active figuration and

embellishment about these

predetermined notes. In this

work by Bull, the cantus

firmus can be heard

quite clearly in the long

notes in the top voice,

beginning with the pitches a,

c, a, a, g, c, d, c.

These notes are the

beginning of the chant

“Gloria tibi trinitas” and

this particular chant has

served as the cantus

firmus for an enormous

number of compositions -

over one hundred pieces for

lute or keyboard in the

sixteenth century use it and

it occurs in even more

pieces for consorts of viols

and other ensembles. Many of

these pieces are titled “In

nomine”, following the title

which John Tavener used for

a keyboard transcription of

a mass section where the

text “In nomine” happened to

appear.

The side ends with a

monumental fantasia by

Philips. He begins with a

musical idea taken from

another fantasia by William

Byrd and subjects this to a

wide variety of treatment in

the course of the piece.

This musical idea appears

several times in the

original note values (the

entrances numbered 1 to 18

in the score); then, at just

the point in this recording

where the organ registration

adds the bright mixture

stops, the subject appears

in diminution (or faster

note values) and in stretto

(or overlapping appearances

of the subject). The third

section (entrances numbered

28 to 31) is played on still

another change of

registration as the subject

appears now in augmentation

(or slower noie values). The

work concludes with further

use of diminution and

stretto and a return to the

original note values.

Side

B - The first

use of these three

works by Gibbons are

brief but beautiful

miniatures; hearing

them in this highly

reverberant organ

performance makes it

easy to imagine their

use as interludes in a

liturgical service.

Indeed the “prelude”

was undoubtedly so

used since it is

called “A Short

Voluntary” in a

different source (and

“A Fancy" in still

another). Despite the

organ performance

which seems so natural

for these works, all

three are performed as

they appear in Benjamin

Cosyn's Virginal

Book. The third

piece is a more

expansive work, with

considerable variety

of expressive content

within a prevailing

quiet and serious mood

that seems so typical

of the music and

musical personality of

Gibbons.

The term “ground”

refers to the

foundation of certain

pieces; specifically,

the ground bass (in

Italian basso

ostinato) is a

musical phrase that is

repeated continuously.

Here the ground is the

scalewise passage d,

e, f, g, a, a, d,

in alternating long

and short note values.

While it would be easy

for the listener to

“lock onto” the ground

itself as it becomes

more and more familiar

through repetition,

the interest and

momentum of the piece

is more in the

figuration that

accompanies the ground

and weaves arabesques

about it.

“Miserere” seems to be

another chant, like

“Gloria tibi

trinitas,” and is the

cantus firmus

Byrd uses in this

piece. It is audible

throughout the work

even though it is

“hidden” in the alto

voice rather than in

the more prominent

melodic or bass voice.

The collection

concludes with a

fantasia by Byrd. In

the first section,

which consists of

twelve numbered,

entries of the same

“subject,” and the

second, which is a

little brighter, the

music is nonetheless

somewhat sober. Then a

more cheerful section

begins with a lively

subject; this yields

to an even more

playful section with

sharply articulated

short and incisive

ideas. A scalewise

passage is added to

the texture and the

rhythms become more

and more dancelike

until the meter

changes into the

rollicking triple-time

dance known as the

corranto. In this

section, the organ

again brings out the

many written echo

effects. The brief

concluding section

consists mostly of

flourishes in one hand

with sustained chords

in the other, bringing

the fantasia to a

brilliant close.

The organ used is the

63-stop Schnitger at

Zwolle, Holland. It

was built in 1721, two

years after the death

of Arp Schnitger, by

his two sons following

in the footsteps of

their illustrious

father (whose work won

such praise from J. S.

Bach).

The Zwolle Schnitger

was chosen by Mr.

Leonhardt as offering

the best

approximation, among

accessible old

instruments, of the

sounds and ambience

available to these

composers. This

marvelous

reverberation must

indeed be close to

what Bull knew in

Antwerp, Gibbons in

Canterbury and Tomkins

in Worcester.

Notes

by William

Pepper

|

|

|

|