|

|

1 CD -

042 - (c) 2003

|

|

| Clavierorganum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hans Leo HASSLER (1564-1612) |

Canzon |

|

2' 29" |

1 |

| Nicholas STROGERS (?-1575) |

Fantasia |

|

3' 01" |

2

|

| William BYRD (c.1542-1623) |

Corranto |

|

1' 13" |

3

|

|

Queens Alman |

|

4' 03" |

4 |

|

Ground |

|

3' 41" |

5

|

| John BULL (1563-1628) |

Bull's Goodnight |

|

3' 31" |

6

|

| Orlando GIBBONS (1583-1625) |

Fantasia

II |

|

2' 58" |

7 |

| Johann PACHELBEL (1653-1706) |

Fantasia |

|

2' 42" |

8 |

| Johann Christoph BACH (1642-1703) |

Praeludium

|

|

5'

19"

|

9 |

| Johann PACHELBEL |

Toccata

in G |

|

1' 30" |

10 |

| Christian RITTER (1650-1725) |

Allemanda

in discessum Caroli XI regis Sueciae |

|

5'

08"

|

11 |

| Johann Sebastian BACH (1685-1750) |

Fantasia,

BWV 1121 |

|

2' 47" |

12 |

|

Aria

variata, BWV 989 |

|

15' 17" |

13 |

|

Partie

sopra "O Gott, du frommer Gott", BWV 767 |

|

15' 31" |

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gustav LEONHARDT |

|

- Claviorganum de

Matthias Griewisch, 2001 (1-11)

- Clavecin allemand d'Anthony Sidey,

1995 (12-14)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Chapelle de l'hôpital

Notre-Dame de Bon Secours, Paris

(Francia) - febbraio 2003 |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Alpha |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Hugues Deschaux |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Alpha - ut

pictura musica | 042 |

1 CD - durata 70' 15" | (c) 2003 |

DDD |

|

|

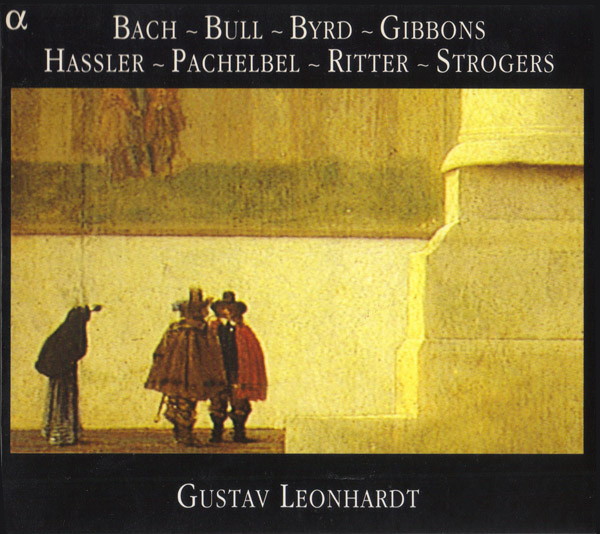

Cover Art

|

|

Pieter Jansz.

Saenredam, Interior of St

Bavo's Church in Haarlem,

1648 Edinburgh, National Gallery

of Scotland |

|

|

Note |

|

Digipack

|

|

|

|

|

Pieter

Jansz. Saenredam

(Assendelft, 1597 - Haarlem,

1665)

Interior

of St Bavo's Church in

Haarlem, 1648 (Oil on

panel, 200 x 140 cm)

Edinburgh,

National Gallery of Scotland

The images of

the previous faith have been

whitewashed over, but the

interior of Haarlem's Gothic

cathedral is nevertheless

magnificent in its present

bareness. The Calvinist faith,

based on Scripture rather than

on the exteriorisation of

religious feeling, has

rejected the former

decoration, which was not in

accordance with Protestant

sensibility. Disapproving of

the Roman Catholic Church's

role as mediator and its

theatrical pomp, Calvinism

advocates a simple, direct

relationship with the Creator,

experienced in an atmosphere

of austen'ty. Neveitheless, a

number of heraldic elements,

diamond-shaped coats of arms,

are visible here and there on

the columns as reminders of

the tight against the Spaniard

or the merits of some group,

guild, family or individual

that played some part in the

setting-up of the new

political order based on civic

liability, whose values tally

with the spirit and the

precepts of the new faith. The

pulpit and other furniture

relating to the rite, the

ornate chandeliers punctuating

the nave between the

impressive blind arcades, the

wind rose familiar to the

navigators of the 'golden age'

of the powerful Dutch navy:

all these have survived, or

pertain to the metamorphosis.

The organ on the night, its

Flamboyant-style case seen in

profile level with the

triforium, has escaped

destruction. Music was the

subject of heated debate among

theorists of the new religion.

While some associated it with

the frivolity and ostentatious

excesses of the papacy, and

with the pleasures of somewhat

impious clerics, a large

section of the Reformed church

nevertheless recognised its

íntrinsic spiritual value.

While the congregation,

assembled to proclaim God's

Word, sang without

accompaniment, the organ was

played outside the church

services at sacred concerts.

The imposing presence of this

instrument undoubtedly

represents a passionate and

nostalgic stand on behalf of

music. Saenredam seems to have

been particularly fond of this

very beautiful old organ,

which had been restored

shortly before the picture was

painted: it appears in several

of his works. Furthermore,

biblical verses, clearly

visible in a decorative band

running round the instrument,

are used in support of

rnusic's role as a vehicle for

the singing of Gods praises.

The raised ceiling (partly

made of wood) with its

delicately intersecting ribs

is decorated here and there

with fine rinceaux -

scrolls of formalised leaves

and stems: the only departure

from the prevailing restraint,

austerity and soberness of the

interior. The painter uses the

larger-than-life columns to

intensify the impression of

verticality and suggest

celestial harmony. Rather than

drawing the eye towards a

single vanishing point,

following the rules of

perspective set forth by

Alberti (Della pittura,

1436), the painter creates two

focal points, thus enlarging

the field of vision and giving

the viewer more room for

contemplation, Saenredam is

quite rightly considered to be

a master of this art based on

geometry, but that does not

prevent him from bending the

rules to suit his aesthetic

intention. His artistic

freedom is seen in the

“counter-perspective” of the

decorated vault at the

intersection of the central

bay. By multiplying the views

the painter enriches the

discourse. Though descriptive,

the 'church portrait', of

which Saenredam was a pioneer,

was not meant to be purely

objective and realistic: like

any work of art, it serves to

achieve the authors expressive

aims. The painter's method is

based on a very accurate and

meticulously detailed

observation of architecture in

situ, but the final

result is nevertheless

creative, imaginative and

evocative.

Although the vertical

dimension takes precedence,

the horizontal plane is also

asserted by the introduction

of discreet narrative

elements, which nonetheless

attract the viewer's

attention. Standing on the

slate floor, which has been

raised to make it more

visible, and which contrasts

strongly with the delicate

shades of brown, beige, grey

and silvery white that

predominate in the rest of the

building, the tiny figures on

the left indicate not only the

scale of the painting but also

the cathedral's colossal

proportions. Seen conversing

beneath a picture on the wall

- a work within the work, a

tapestry, perhaps, or a fresco

(although the latter was rare

in northern Europe), possibly

evoking one of the artists own

paintings - these burghers

tell us something about daily

life in Holland, where the

church served not only for

worship but also as a public

meeting place. The transverse

(`melodic') axis crosses the

main vertical ('harmonic')

axis, rising to the vaults.

Saenredam was an indefatigable

explorer of churches and an

unsurpassable poet of

religious architecture.

Supported by a clear

architectonic structure, a

feeling of order, silence,

meditation, peace and serenity

prevails in this picture. The

subtle, atmospheric light

coming in through the many

windows creates tonal unity,

merging and mellowing the

parts.

Less than fifty years before

the birth of the greatest

architect of Western music,

Saenredam expresses the

transcendent clarity, the

monumentality and the perfect

form that were to be taken to

hitherto unattained heights by

J.S. Bach. With its aesthetic

and mystical qualities, the

vast nave symbolises the

cosmic balance of the

universe. Set firmly on the

ground, concrete and tangible,

the small figures represent

the microcosm; they provide

the touch of anecdote that

brings out the abstract formal

perfection of the work as a

whole. The movement of

contemplation induced by art

music, sacred or secular, is

not severed from its

vernacular source; music of

popular origin is none the

less noble and worthy of

permanence. The classical

language, in both music and

painting, transfigures reality

while retaining its essence,

and thus makes it lasting.

Denis

Grenier

Department

of History

Laval

University, Quebec

Translation:

Mary Pardoe

The

Italian legacy

Italy's

contribution to music, and to

the arts in general, is

unparalleled. Although it

remained politically

fragmented for centuries

(unifìcation was not achieved

until the nineteenth century),

by the Quattrocento it had

become the cultural centre of

the Western world. Its

creative approach based on the

elaboration of obiective

techniques, in painting,

sculpture, poetry and music,

appealed to the whole of

Europe. Each of the great

centres - Florence, Rome,

Bologna, Venice, Mantua,

Milan, Modena - had its own

artistic identity, yet viewed

from the outside that identity

is nevertheless Italian.

Italian vocal music, both

sacred and secular, is of

course of legitimate

importance, but we must not

forget the great influence

Italy had on instrumental

music, and particularly

keyboard works, in the

sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries. In our recording of

harpsichord pieces by Girolamo

Frescobaldi and Louis Couperin

(Alpha 026) we approached the

complex relationships between

Italy and France. Here we turn

to the Italian influence on

English and Germanic

composers.

Why use the rather vague word

'keyboard'? Why not refer more

specifically to the

harpsichord, organ, virginal,

spinet or claviorganum, all of

them keyboard instruments?

Musicians of that time were

pragmatic; rather than

specifying the instrument, and

therefore narrowing the

destination of their works,

they preferred to leave the

player to make his own choice,

depending on his tastes and,

above all, on instrument he

had at his disposal. Early

seventeentb-century treatises

(Mersenne, Kircher,

Praetorius...) show what a

wealth of keyboard instruments

existed side by side at that

time, without any hierarchy.

The claviorganum, which seems

almost exotic to us today, was

then quite commonplace.

Furthermore, the earliest

surviving harpsichord made in

England is part of a

claviorganum.

Hans Leo Hassler (1564-1612),

an organist and composer of

great repute, was regarded

during his lifetime as one of

Germany's fìnest musicians.

Born in Nuremberg, he was

appointed director of town

music there in 1601, before

moving to Ulm in 1604, then

being appointed electoral

chamber organist in Dresden in

1608. He received his early

musical training in Nuremberg,

with a former pupil of Roland

de Lassus. In 1584 he was sent

to Venice to study with Andrea

Gabrieli, master of the art of

the ricercar and the canzon, a

polyphonic instrumental form

which gradually gained

independence from its vocal

model, as did the fantasia.

The Fantasia by the London

organist Nicholas Strogers (fl

1560-75) still shows signs of

its Italian origin.

One of Strogers' great

compatriots was William Byrd

(1545-1623), who was a prolific

composer of excellent keyboard

works. Like other English

musicians of his time, Byrd

was affected by the events of

the English Reformation, when

the English Church separated

from Rome under Henry VIII and

papal authority in England was

destroyed. The decision

created terrible tensions

between Anglicans and

Catholics who remained

faithful to Rome. Byrd was a

Catholic, 'a stiff papist and

a good subject', but his

stature as an artist earned

him the favour of Elizabeth I

(who, like her father Henry

VIII, was an amateur

musician). He was admitted to

the Royal Chapel in 1570, both

as a Gentleman and as joint

organist with Tallis, and no

one troubled him when he

published a volume of Catholic

music in 1605. If his vocal

music for Anglican or Catholic

worship was his main source of

pride, his music for virginals

shows outstanding creative

skill. A few of these pieces

were published in 1615 in Parthenia,

the first book of keyboard

music printed in England,

containing twenty-one pieces

by Byrd, and the younger

composers Bull and Gibbons - Parthenia,

or the Maydenhead of the

first Musicke that ever was

printed for the Virginalls.

Other instrumental music by

Byrd is preserved in

manuscripts compiled for

patrons or by admirers, such

as the exquisite My Ladye

Nevells Book, dated

1591, and the vast Fitzwilliam

Vírginal Book. The

latter was compiled by Francis

Tregian, a Catholic recusant,

during his years of

imprisonment in the London

Fleet Prison from 1609 until

his death in 1619. It contains

not only numerous compositions

by Byrd, but also many pieces

by Bull, Farnaby, Strogers and

Morley.

Dances formed the basis of

much of the music of that

time; the Corranto, Galliard

and Jig did not conceal their

Italian origins, but they

often came close in melody and

rhythm to the typically

British country dance. In this

Byrd carried on the earliest

English keyboard tradition, a

fine example of which is Hugh

Aston's extraordinary Hornepype,

composed around 1500. He also

took an interest in the theme

and variations, which allowed

the composer great creative

scope. His Queenes Alman

is in fact a set of three

variations on one of the most

popular songs of the time, Une

jeune fillette. The

subject of the song - the

lament of the young girl

forced to become a nun - first

appeared in Sienna in the

fifteenth century.

Une

jeune fillette / A young maid

De noble

coeur / Noble minded

Plaisante et

joliette, / Amiable and

pretty

De grand'

valeur / And of great

merit

Contre son

gré, on l'a rendue nonnette

/ Was made a nun against her

Will

Cela point

ne lui haicte / And as

it pleased her not

Dont vit en

grand douleur. / She lived

in great sorrow.

The melody

found its way to other parts

of Europe. In Italy it became

the popular song La Monica,

and Frescobaldi and Scheidt,

amongst others, composed

variations on the tune. In

Germany we find it in the

Works of Hassler, in the song

Ich gieng einmal spazíeren

(variations) and in the

chorale Von Gott will ich

nicht lassen (melody).

In France, Eustache du Caurroy

used it for one of his

Fantasies of 1610 and for a

Christmas hymn entitled Une

jeune pucelle. In the

Netherlands, the Van Soldt

Manuscript presents it as L`Allemande

de la nonnette, and it

was even published in Toronto

in 1643 as a Huron hymn.

The last piece by Byrd

presented here is a Ground.

It consists of a three-note

thematic motif in the bass

which is constantly repeated

with changing harmonies while

the upper parts proceed and

vary.

John Bull (?1562/3-1628) was a

Catholic like Byrd, but he did

not suffer for his religion.

In 1613, however, he became

involved in a serious scandal

and was forced suddenly and

secretly to leave England for

the South Netherlands; from

1615 he was organist of

Antwerp Cathedral. He never

returned to England. From 1586

until his exile he had been a

Gentleman of the Chapel Royal.

And he became a Doctor of

Music at Oxford in 1592, which

explains why several of his

works are signed “Dr Bull”. He

was recognised as one of the

finest English composers and

contributed to the famous

collection Parthenia

of 1613. Bull's Goodnight,

with its evocative but

inexplicable title, takes the

form of nine charmingly

voluble variations on a short

theme. Full of detail, the

piece calls for great

dexterity.

The last famous composer whose

works appeared in Parthenia

was Orlando Gibbons

(1583-1625). He became a

Gentleman of the Chapel Royal

(date uncertain), of which he

was senior organist by 1625,

and he was organist of

Westminster Abbey from 1623.

He was regarded as the most

skilful keyboard player of his

day. His compositions,

including the Fantasia

presented here, are similar in

style to those of Frescobaldi.

Like Hassler, Johann Pachelbel

(1653-1706) was born in

Nuremberg. He was a Lutheran,

and after training at Altdorf,

then Ravensberg, he went to

Vienna in 1673 to become

organist of St Stephens

Cathedral, where he would

certainly have been exposed to

the works of Catholic

composers of Italy as well as

southern Germany. His style

was strongly influenced by

that of Froberger, who studied

with Frescobaldi. His music

amalgamated both German and

Italian styles and marked the

beginning of the diffusion of

an Italian manner that was to

live on for several decades.

On his return to Germany he

became court organist at

Eisenach (1677), before moving

to Erfurt in 1678 as organist

of the Protestant

Predigerkirche. During his

years at Eisenach and Erfurt,

he was naturally drawn to the

Bach family, and he taught

music to Johann Christoph

Bach, Johann Sebastian's

eldest brother. He was

organist at Stuttgart, then at

Gotha, before returning to

Nuremberg in 1695.

Pachelbel's Toccatas are

generally Italianate, quite

short, and based on a single

thematic cell, while Johann

Christoph Bach's Praeludium

belongs more to the world of

the German stylus

phantasticus. Johann

Christoph Bach (1642-1703),

who was the cousin of Johann

Sebastian Bach's father, was

one of the most interesting

musicians of the late

seventeenth century. He worked

at Eisenach as organist, then

as a member of the court

Kapelle (where he no doubt got

to know Pachelbel). Sensitive

to injustice, he spent many

years battling with the town

council for better treatment

as a musician, thus prefiguring

a similar spirit in Johann

Sebastian. To be sure of

obtaining payment when he

played at weddings, he

proposed that the marriage

certificate should be

delivered only on receipt of

his fees! Johann Christoph

Bach's vocal and instrumental

works are a delight. He left

some magnificent motets, which

may have served as a model for

Johann Sebastian, including Lieber

Herr Gott for two

choirs, as well as isolated

pieces such as the famous

Lamentatio: Ach, dass ich

Wassers gnag hätte, a

musical declamation in which

the music follows the text

step by step. His Praeludium

in E flat (transposed

here to C) is in fact a

prelude and fugue, like those

later to be found in Das

wohltemperierte Klavier. An

overture in the form of an

Italian-style toccata is

followed by a chromatic

four-part fugue, very clear in

structure; the conclusion is

vehement and almost

improvisational.

After his parents died, Johann

Sebastian Bach was taken in by

his brother Johann Christoph,

organist at Ohrdruf. His

biographers tell us that

Johann Sebastian spent long

hours reading by moonlight the

scores that his brother had

collected (and mention that

this was probably one of the

causes of his subsequent

blindness). Johann Christoph

copied out compositions,

compiling anthologies. And

that is how we come to possess

the Suite by Christian Ritter

from which the Allemande

on the death of Charles XI

of Sweden is taken, a

piece is directly descended

from the tombeaux of Froberger

or Louis Couperin. It is

included in the Möller

Manuscript, along with pieces

by Zachow, Böhm, Lully and

others. Ritter

(c1645-after1717) was court

organist at Halle, then at

Stockholm, where he became

Kapellmeister in 1699.

The Italian influence was

clear throughout the life of

Johann Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750), and the

particular influence of

Vivaldi`s concertos can be

seen in his numerous concerto

arrangements. It is also

obvious in some of his early

individual pieces, such as the

very touching Fantasia

BWV 1121, a piece combining a

delicate melodic line with a

subtle use of counterpoint.

And even more so in the Aria

variata alla maníera

italiana BWV 989,

probably composed before 1710

and included in the “Andreas

Bach Buch”, into which it was

copied by Johann Christoph

Bach, in the early eighteenth

century. Although Bach was

probably not yet twenty-five

years old at the time of

composition, this set of

variations shows a perfectly

well organised creative mind.

We do not know whether the

Aria which serves as a theme

for the variations, with its

very unusual harmonic

relationships, was written by

Bach himself or whether he

took inspiration from a

pre-existing melody. He uses

it for ten variations, each

one making the most of some

rhythmic or harmonic element

from the theme. We cannot help

being reminded of the Goldberg

Variations, which Bach

composed later in his life.

The theme itself and the last

variation are for four voices;

all the variations in between

are for two voices. Sometimes

the writing calls to mind

Italian violin compositions,

and we wonder if the piece was

not originally written for

violin and continuo, although

the homogeneous treatment of

the lines is perfectly suited

to performance on a keyboard

instrument.

The Partitas (or

variations) on the chorale O

Gott, du frommer Gott

BWV 767 are generally included

among Bach's organ works. But

they were probably intended

for the harpsichord. Many

aspects are more typical of

harpsichord writing: the

linking of chords in the

exposition of the chorale, the

ornamentation, the arpeggiated

formulas, the analogies with

movements of the dance suite,

the 'concerted' nature of the

final variation. And the work

also appears to belong to the

'Hausmusik' genre - music

intended for performance in

the home by family and friends

for their own entertainment

and edification. Such music was

common at the time of the

Reformation and similar

partitas were written by Georg

Böhm and Pachelbel. Unlike the

chorale prelude, intended to

introduce the hymn tune to be

sung by the congregation, the

chorale partita, a set of

variations based on a chorale

melody, does not require a

vocal interpretation; it may

be seen as a substitute for,

or a paraphrase of the hymn.

This work dates from the years

1702-1707, when Bach was still

a very young composer. It is

based on the words of a

chorale by Johann Heerman

(1630) and a melody that was

first published in 1648.

Curiously, Bach did not use

the same very beautiful melody

again when he decided to use O

Gott, du frommer Gott as

the final chorale of his

cantata BWV 24. Heerman's text

- a spiritual reflection on

the finality of existence, a

theme that was common at that

time - is in eight verses. And

there are nine Partitas.

It is therefore difficult to

imagine a close concordance

between the words and the

music, unless we assume that

the first Partita is

meant to be a sort of

introductory sinfonia. In that

case the correlation that

emerges is sometimes quite

remarkable. The second Partita,

for example, with its

persistently repeated phrase

on the left hand, corresponds

to the image of God as an

eternal source of goodness

(verse 1). In the fourth Partita,

the power of the Word (verse

3) is possibly represented in

the vehemence and constant flow

of the music on the right

hand, supported by a very

strong rhythm on the left. The

chromatic lamento of the

eighth Partita may

also be compared with the

words about death in verse 7,

and the exhilarating character

of the final Partita

with the reference to the

Resurrection in the last

verse. Although these are

merely conjectures, they

nevertheless fit in with the

declamatory conception of

music that was prevalent in

the seventeenth century. We

must not forget that much of

Bach's early (extra-musical)

education stemmed directly

from the ideas of the

Renaissance, and that the

general teaching he received

was in keeping with that

perspective, notably at

Lüneburg, where the rich

library contained, amongst

other works, a copy of Athanasius

Kircher's Musurgia

Universsalis. This very

influential work of music

theory, regarded as a

reference at that time in the

Germanic world, emphasised the

closeness between music and

declamation, while giving the

advantage to the former for

its capacity to express human

emotions - a notion that was

central to Baroque thought.

Therein lies perhaps the most

constant aspect of Italy's

legacy, for the question of

the relationship between the

poetic text and the music was

posed at a very early date in

the peninsula, giving rise to

opera on the way. Thus,

'musical rhetoric during the

Baroque era achieved its true

aim from the moment that it

began to take into account the

reception of a musical work,

its effect on the audience,

its emotional dimension'.

In a way, the extraordinary

development of keyboard music

reflects the quest for that

eloquence that has no need for

words in order to be

expressive and to move the

listener.

Jean-Paul

Combet

Translation: Mary

Pardoe

|

|

|

|