|

|

1 CD -

017 - (c) 2001

|

|

| L'orgue Dom

Bedos de Sainte-Croix de Bordeaux |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| François COUPERIN (1668-1733) |

Messe

propre pour le couvents de religieux

& religieuses (extraits)

|

|

17' 31" |

|

|

-

Plein Jeu - Premier couplet du Kyrie |

1' 25" |

|

1

|

|

-

Dialogue - 5ème & dernier

couplet du Kyrie

|

2' 00" |

|

2

|

|

-

Chromhorne sur la Taille - 5ème

couplet du Gloria |

2' 36" |

|

3 |

|

-

Récit de tierce - 8ème couplet du

Gloria |

1' 38" |

|

4

|

|

-

Offertoire sur le grands jeux |

5' 33" |

|

5

|

|

-

Elévation - Tierce en Taille |

3' 16" |

|

6

|

|

-

Agnus Dei |

1' 03" |

|

7 |

| Abraham van den

KERCKHOVEN (1618-1701) |

Fantasia |

|

5' 33" |

8 |

| Johann Kaspar

Ferdinand FISCHER (1665-1746) |

Chaconne |

|

4' 34" |

9 |

| Georg MUFFAT (1653-1704) |

Toccata

Prima

|

|

5'

19"

|

10 |

| Louis MARCHAND (1669-1732) |

Plein-jeu |

|

1' 03" |

11 |

|

Basse

de cromhorne |

|

1'

10"

|

12 |

|

Duo |

|

0' 55" |

13 |

|

Récit

& Dialogue |

|

3' 36" |

14 |

| John BLOW (1649-1708) |

Voluntary

IV

|

|

3' 15" |

15 |

|

Voluntary

VIII |

|

4' 51" |

16 |

|

Voluntary

XVIII |

|

2' 55" |

17 |

| Georg MUFFAT

|

Toccata

Quinta |

|

6' 07" |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gustav LEONHARDT,

Orgue Dom Bedos - Pascal Quoirin de

l'abbatiale Sainte-Croix de Bordeaux |

|

Tadashi Watanabe, accordatore

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Bordeaux (Francia) -

giugno 2001 |

|

|

Registrazione: live

/ studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Alpha |

|

|

Recording Engineer

/ Editing

|

|

Hugues Deschaux |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Alpha - ut

pictura musica | 017 |

1 CD - durata 57' 35" | (c) 2001 |

DDD |

|

|

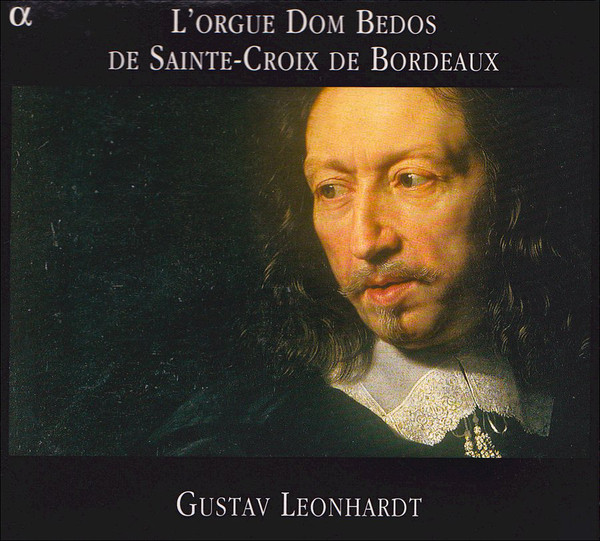

Cover Art

|

|

Philippe de

Champaigne, Portrait d'homme,

Musée du Louvre |

|

|

Note |

|

Digipack

|

|

|

|

|

Philippe

de Champaigne or Champagne

(Brussels 1602 - Paris 1674)

Portrait

of a man, 1650 (Oil on

canvas, 91 x 72 cm)

Paris, Musée

du Louvre

Philippe de

Champaigne felt little

sympathy for the universe of

Rubens. In 1621 he left

Flanders, intending to travel

to Italy, and stopped in Paris

where, after returning briefly

to Brussels in 1628, he was to

spend the rest of his life. As

painter to Marie de Médicis at

the Luxembourg Palace, he kept

company with Poussin, and

enjoyed the favour of Louis

XIII and Richelieu; their

sensibility coincided with the

aesthetic position of the

Flemish artist, perfectly

adjusted to the culture of his

adopted country. He received

commission after commission:

official effigies, the Gallery

of Illustrious Men at the

Palais Cardinal, the Sorbonne

chapel... Anne of Austria and

Mazarin also called on his

services. Little inclined to

celebrate the triumphant and

worldly conception of religion

prevailing under the Regency,

but much more in tune with the

austere religious sentiment

that inspired the Jansenists,

he became associated with

Port-Royal in the 1640s. This

portrait, once said to be of

Arnauld d‘Andilly, seems to

come from this milieu.

Behind the

frame of a window that opens

onto a blind wall, squeezed

into his narrow abode, the man

gazes towards his right. Over

the tunic covering his

lace-edged shirt, a voluminous

dark blue coat, velvety in

texture, deploys its ample and

supple folds, and lends the

subject nobility and dignity.

Yet the painter does not

flatter him: a face with a

broad forehead scrutinised

without indulgence, protruding

eyes, a squint [?], an

unprepossessing nose, a scar,

balding temples, drooping

hair. Placed on the edge of

the frame, his right hand,

keystone in the illusionist

trompe-l'oeil, points

downwards, in counterpoint to

the head turned the other way:

nature seeks a balance. And

nature is indeed the absolute

point of reference of Flemish

visual culture, preoccupied as

it is with rendering outward

appearance.

Mingled with a

typically French reserve and

discretion, realism and colour

(reduced, but sumptuous) and

the spiritual quality of the

light breathe life, beauty,

and grace into this objective,

and introspective, human

presence. The native northern

characteristics fit in easily

with the painters classical

temperament, perfectly in tune

with the predominantly ascetic

tendency of Parisian art of

the 1650s, the melting pot

from which the classicism of

Louis XIV’s reign was to

emerge. An artistic synthesis

appropriate to the discreet

world of the recluses whose

logicians cultivated the clear

ordering of thought. Is the

man portrayed here one of the

’gentlemen‘ of that retreat

amid the fields that was

Port-Royal? The overall

atmosphere of the painting,

which is not without recalling

the severe probity of certain

portraits associated with

Dutch Calvinism, leads one to

think so.

Denis

Grenier

Department

of History

Laval

University, Quebec

Translation:

Charles Johnston

Dom

Francois Bedos de Celles

François de

Bedos de Celles was born in

Caux, into a noble family of

the diocese of Béziers, on 24

January 1709, and studied at

the Oratorian college in

Pézenas. He entered the

Benedictine order at the

monastery of La Daurade at

Toulouse on 7 May 1726. We

know nothing of his years of

apprenticeship as an

organ-builder except for the

fact that he became friendly

with Jean-François l‘Epine l‘aîné,

and was to keep in close

contact throughout his life

with the latter‘s two sons

Jean-François and Adrien, both

of whom also entered the

profession. He was already

known for the quality of his

work when he was called to the

abbey of Sainte-Croix at

Bordeaux in the early 1740s by

its prior Dom Joseph Goudar.

Elected secretary of the abbey

chapter in 1745, he began

around that time to build a

16' organ with five manuals

which was finished in 1748. As

a recognised builder, he was

often invited to build,

repair, or give expert opinion

on other organs, or to advise

their builders: thus he

visited Clermont-Ferrand,

Sarlat, Le Mans, Montpellier,

Dijon, Pézenas, Toulouse,

Tours, Narbonne and Paris,

amongst other towns.

As a monk of notable

erudition, Dom Bedos was

elected to membership of the

Académie Royale des Sciences

of Paris in 1758 and admitted

to the Académie Royale of

Bordeaux the next year. In

1760 he wrote and published a

treatise entitled La

Gnomonique pratique ou l’Art

de tracer les cadrans

solaires avec la plus grande

précision (Practical

gnomonics or the art of

plotting sundials with the

greatest precision).

In 1763 he retired to the

abbey of Saint-Denis, where in

1766, in response to a

commission from the Académie

Royale des Sciences of Paris,

he began to write a treatise

on the theoretical and

practical aspects of

organ-building which was to

take up the last years of his

life. Published from 1766 to

1778, L’Art du Facteur

d’Orgues is a monumental

survey of the French classical

organ of the eighteenth

century, which is still

accepted as the authoritative

work by today's

organ-builders. Dom François

died on Thursday 25 November

1779, and was buried in the

abbey cloisters the next day.

In his memoirs,

Ferdinand-Albert Gauthier,

organist of Saint-Denis from

1763 to 1795, speaks of him in

these terms:

He was a man of exceptional

merit, who did honour to the

abbey of Saint-Denis by his

great talents. [...] This

artist excelled in several

spheres. A man so precious and

refined is but rarely

encountered, and it is

difficult to imagine the full

extent of his qualities. He

was a learned mathematician,

and made all his own tools and

instruments. He used to say

that he would not have found

workmen of sufficient skill to

make them for him. In sum, he

was one of those men who are

useful to Society, and to this

he added the qualities of a

good monk: gentle, affable,

obliging and very

hard-working, esteemed by the

erudite and enjoying a

reputation well earned through

the superiority of his

talents, on which he never

prided himself.

The Dom

Bedos organ of the former

abbey church of

Sainte-Croix, Bordeaux

1. The

Great organ of an abbey at

the peak of its prosperity

The construction of the

instrument by Dom Bedos is

authenticated by an

inscription specifying the

date of 1748 and the name of

the prior at the time, Dom

Joseph Goudar. Until the

recent restoration of the

instrument, its stop-list was

not known with absolute

certainty, owing to the fact

that the inventories by

Bordonneau (1756) and Lavergne

(1795) contradict each other

on several important points.

It was known that the

instrument was a large 16‘ one

with five manuals and a 32’

Bourdon on the Grand orgue,

and that it comprised 44 or 45

stops. Lavergne, whose task

was to value the property

confiscated from the monastic

congregations and the clergy,

also specifies that the case

was ‘painted green, with all

its mouldings and decorations

gilded‘. When he finished this

instrument, Dom Bedos was aged

thirty-nine, and he was

perhaps putting his name to

the finest achievement of his

whole career as an

organ-builder, and certainly,

in any case, the most

important organ by him that

has come down to us: it stands

comparison with the greatest

instruments of the kingdom,

thanks in particular to the

richness of its grand

plein-jeu, unique in

France today. Indeed, the

instrument that attracts

visitors and music-lovers to

Sainte-Croix appears somewhat

out of proportion to the

relatively modest dimensions

of the abbey church.

2. The vicissitudes of the

nineteenth century: exile

and dilapidation

The Dom Bedos organ came

through the torments of the

revolutionary period without

suffering too much damage:

despite the lack of

maintenance, Lavergne

estimated its value at 100,000

livres in 1795! At the

cathedral of Saint-André, on

the other hand, the monumental

organ by Valéran de Héman,

built in the seventeenth

century, had been totally

destroyed. In the early years

of the nineteenth century the

Archbishop of Bordeaux, Mgr

Daviau, in order to avoid

costly reconstruction, decided

to requisition from his

diocese an instrument capable

of sustaining the pomp of the

archiepiscopal church. His

initial choice settled on the

Micot organ of Saint-Pierre de

La Réole, which boasted some

thirty stops. It was

dismantled and reassembled in

an enlarged case at

Saint-André in 1804.

Unfortunately the result did

not meet expectations, since

the sound of the organ was

lost in the immense nave of

the cathedral. After this

disappointment, the prelate

then started to demand the Dom

Bedos organ from Sainte-Croix

from 1811 on. Despite

opposition from the

parishioners, the soundboards,

action and pipework were

dismantled and exchanged with

those of the Micot organ by

the builders Isnard et

Labruyère in 1817, whilst Dom

Bedos‘ case remained at

Sainte-Croix. This exile

ushered in a long period of

dilapidation of the

Benedictine monk‘s

masterpiece. A restoration

conducted by the Bordeaux

organ-builder Henry in 1857

revealed the deterioration of

the instrument, and also the

poor quality of the work

carried out in 1817. The newly

modifled organ, inaugurated in

1840 maintained by Henry until

1855, was not long in falling

once more into decrepitude. In

1877 it was again restored by

another Bordeaux builder,

Georges Wenner, whose main

contribution was to build a

Romantic Récit of

fourteen stops to replace Dom

Bedos‘ Récit and Écho.

At this time both the case and

the workings of the organ took

on the form in which they

would remain until they were

dismantled in 1973. The organ

now had three manuals and 56

stops, which made use of 2,200

original pipes by Dom Bedos.

According to Canon Lacaze,

organist from 1947 to 1964,

the instrument possessed at

this period ‘one of the

clearest and most sonorous

voices in France‘.

3. The restoration

(1985-1996)

In the 1960s the decrepit

state of the organ led to

extensive restoration being

considered. But what was to be

done with the material from

the time of Dom Bedos that

could still be reused? The

first project was to build a

large instrument in the

neo-classical style. This

provoked a reaction from

supporters of a restoration of

the masterpiece on historical

principles and its return to

Sainte-Croix. The ensuing

controversy saw the interested

parties divided into two

camps. The organist Francis

Chapelet, who advocated a

restoration faithful to the

spirit of Dom Bedos, secured

public support in 1967 from

such personalities as Vladimir

Jankélévitch, Emile Leipp,

Charles Munch, Gustav

Leonhardt, not to mention

Claude Lévi-Strauss. After

three years of argument, the

Commission des orgues et

Monuments historiques

announced its decision in

1970: a new organ was to be

built at Saint-André, and the

Dom Bedos material that had

been conserved there was to be

refurbished and brought back

to its original organ loft. In

1973 the Saint-André organ was

dismantled and the Dom Bedos

material was reunited at

Sainte-Croix. The new organ at

Saint-André, consisting of

seventy-eight stops on four

manuals, was finished by the

firm of Gonzalez-Danion and

inaugurated in 1982.

In 1985 agreement was reached

with the Carpentras firm of

organ-builders headed by

Pascal Quoirin to restore the

Dom Bedos instrument in its

initial case. There remained

of the original instrument

four soundboards from the Grand

orgue, three from the Positif

and two from the pedal, as

well as 2,200 pipes, which

constituted the essential

elements of the material. It

was necessary to reconstruct

the missing pipes, restore

them to the original pitch

(A=392 at 18°), rebuild the

missing soundboards for the Récit

and the Écho,

reconstruct the action and the

console with its five manuals,

rebuild the seven wedge

bellows, and restore the case

by getting rid of the dark

coating that had been applied

to it in the nineteenth

century in order to uncover

the splendour of the initial

colours, celadon and gold.

Over the eleven years

necessary for the work, a

process of deduction,

observation of the remaining

traces of the original

condition of the case and

soundboards, and utilisation

of the information available

in L’Art du Factear

d’Orgues resulted in the

rediscovery of the precise

stop-list and original pitch,

the compass of the manuals and

pedal-board, and the sumptuous

decoration of the 48 painted

labels naming each stop, which

had been concealed by nailed

planks at the time of Wenner‘s

restoration. The instrument is

tuned in adjusted mean-tone

temperament.

The end result, inaugurated in

1997, has received unanimous

praise from organists from all

over the world. The

thirty-two-foot Grand

plein jeu, whose

opulence and majesty are

unique in France, is combined

with a grand jeu of

exceptional vigour. There can

be no doubt that this

restoration marks the

culmination of the movement of

rediscovery and restoration of

French classical instruments

that began in the early

twentieth century. In addition

to the inherent quality of the

restoration work, the very

name of the builder

responsible for the original

organ guarantees it a place as

one of the most fascinating

instruments in the whole of

Baroque Europe.

Jean

Barraud

Translation:

Charles Johnston

The

construction of the Dom

Bedos organ

of the

abbey church of

Sainte-Croix, Bordeaux

during

the Maurist reform

In 1627, the

great François de Sourdis,

Archbishop of Bordeaux and one

of the leading figures of the

Catholic Reformation in

France, imposed on

Sainte-Croix abbey the reform

of the congregation of St

Maur. This was the prelude to

an upturn in the abbey’s

fortunes that was to last 162

years, coinciding with the

Baroque period in music and

art.

The church of Sainte-Croix,

whose organ gallery houses the

masterpiece of Dom François

Bedos de Celles, was at that

time the chapel of the

important monastery of the

same name, which the

Benedictines bad restored

shortly before the year 1000.

It had been founded in

Merovingian times, and

contained the tomb of a

venerated holy man named

‘Mommolenus’, but was later

devastated by the Vikings. The

abbey achieved a new lease of

life around 980, with its

temporal power assured by

particularly rich endowments.

The monks showed considerable

skill in furthering the

prosperity of their vast

domain, part of which was

devoted to vineyards. The

eleventh and twelfth centuries

saw the construction of the

spacious abbey church in the

Romanesque style, with its

nave of five bays — its

northern aisle was given over

to parish functions.

The English protection which

led to the expansion of the

Gascon vineyards further

contributed to the abbey‘s

riches. But the power of the

abbots, who held their office in

commendam from 1439, was

not conducive to the

maintenance of a strict

religious life; discipline

became lax, the buildings were

allowed to deteriorate.

However, the Maurist reform

restored the abbey to its

former plenitude in the

Baroque era.

The church was newly furnished

and decorated according to the

recommendations of the Council

of Trent. Retables were

erected, a certain Bourgneuff

painted an Exaltation of

the Cross in 1636, and

Guillaume Cureau a St Maur

curing one lame with the

palsy and a St

Mommolenus curing one

possessed in 1641 and

1647 respectively. In March

1643, the organ which the

Congregation of the Exempt had

already had repaired around

1584 was once again

overhauled, and then in 1661,

to mark the passage of the

Court on its way back from the

royal wedding at

Saint-Jean-de-Luz, the builder

Jean Haon produced a larger

instrument which used the

existing case and bellows.

Once royal authority was fully

re-established under Louis XIV

after the Fronde, Dom Robert

Ploutier undertook a campaign

of renovation and extension

between 1664 and 1672; the

Romanesque cloister and the

annexes were demolished and

rebuilt, as were the abbot’s

lodgings. To the south-west

side of the church a superb

three-storey building in

classical style, surmounted by

a roof after the manner of

Mansart, was erected; this

imposing edifice, basically

unaltered, was an old people’s

home after 1795, and has

accommodated the Bordeaux

college of art since 1890. The

ground floor housed the

kitchen, the refectory, the

cellary and the classroom for

students; the first floor held

forty cells for the monks and

bedrooms for the sick, whilst

the second floor was given over

to the library. A second large

building was used for the

monastery's guests and for

outhouses. Finally, the abbey

was surrounded by artfully

arranged gardens and by

orchards. In 1735, the garden

was adorned with an exquisite

monumental fountain, conceived

as a nymphaeum, with aquatic

decorations.

The Age of Enlightenment was a

second golden age for

Bordeaux, recalling the

expansion of the period of

English domination. Looking

out over the river, animated

as never before by the comings

and goings of merchant ships,

freed of its obsolete

ramparts, the city offered a

harmonious façade of monuments

in the classical style, and

was adorned by a rich urban

landscape, magnificently

crowned by the Gabriels’ Place

Royale and Victor Louis’ Grand

Théâtre. Back on its feet

thanks to the Maurist rule and

its claustral priors,

Sainte-Croix abbey benefited

from this prosperity.

From 1730, the chapter began

entertaining the idea of

replacing Haon’s organ with an

instrument better suited to

the generous proportions of

the abbey church. Dom Bedos,

‘a highly skilled person and

entirely competent to direct

such matters as were

appropriate for the organ’,

was received into the

community of Sainte-Croix

around 1740 and took up

residence in the monastery.

When he was appointed

secretary to the chapter, on

30 September 1745, he had

already been working on the

plans for a new instrument for

some time. But he had to wait

until the funds needed to

build it could be assembled.

Dom Bedos had an exceptionally

wide knowledge of both the

theory and the practice of the

organ, as well as infinite

curiosity in this sphere - in

1751, for example, he

travelled to the abbey of

Weingarten in Swabia to

examine the organ there, on

the advice of his

fellowbuilder Riepp. The

instrument he produced for

Sainte-Croix was his

masterpiece. A commemorative

plaque affixed to the case

bears the date 1748, but the

receipt for the organ's final

installation dates from 1756,

and an inscription found

inside the instrument during

its recent restoration confirms

that work on it was still in

progress in 1754.

In fact, it was the

exceptional wine harvest of

1748 at Château Carbonnieux,

the Graves estate that the

monks of Sainte-Croix had

purchased in 1740, which

removed the financial

obstacles to the building of

the new organ. And since the

revenue from subsequent

vintages had an equally

positive effect on the abbey’s

books, the completion of this

monumental instrument

proceeded in the most

favourable conditions.

The Carbonnieux estate was a

magnificent property of 122

hectares, situated south of

Bordeaux on the communes of

Villenave d’Ornon, Cadaujac

and Léognan, amid rolling coun

tryside whose ample contours

are further emphasised by the

vine plantations. On 28 March

1740 the monks bought it for

119,000 livres from Charles de

Ferron, a debt-ridden young

man of good family. They did

not hesitate, in order to

‘repair the degraded and

dishonoured vines’, to make an

immediate additional

investment of 80,000 livres,

which had to be borrowed. In

1745, still owing 27,000

livres to Monsieur de Ferron,

the community borrowed 15,000

livres more, ‘to honour those

notes in circulation and to

avoid bankruptcy‘. It is

understandable, then, that Dom

Bedos had to be a little

patient. But the operation

soon showed a profit: in 1748

the wines of Carbonnieux

brought in 20,100 livres - and

the average income rose from

11,000 livres for the first

five years of exploitation to

15,000 for the subsequent ten.

The monks provided Carbonnieux

with extensive outhouses to

store the barrels, and closed

off the courtyard off with a

solid wrought-iron gate, one

of the finest in the region: it

was not only their reliquaries

that needed to be protected

from covetousness. Of the 320

barrels yielded by an average

harvest, a third was white

wine (a proportion of which

was botted), and the monks

kept a third for their own

consumption. Their clientele

included members of the local

aristocracy, but the bulk of

the production was bought by

merchants from Les Chartrons,

the wine-trading district of

Bordeaux. The monks also made

direct sales without middlemen

to Paris, and even as far

afield as Turkey, renaming

their beverage ‘eau minérale

de Sainte-Croix’ for the

occasion! The conjunction of

Carbonnieux and of Dom Bedos'

masterpiece - wine in the

service of the organ - is a

characteristic example of the

refined tastes of the

Benedictines of Sainte-Croix.

Dom Bedos took enormous pains

over the construction of the

Sainte-Croix organ, with the

help of assistants including

Jean Beyssac, also known as

Labruguière. It was also Dom

Bedos who designed the case,

in typical grand siécle

style, with its balance

between the vertical thrust of

the great silvery pipes of the

organ and the refined rhythm

of the gilded rocaille

decorations and volutes. The

woodwork is painted a sober

celadon, from which stands

out, in addition to the gold

of the decorations, the

ultramarine blue of two

cartouches, which display

respectively, embossed in

gold, the Maurist motto Pax

above the three nails of the

Crucifixion, and the monogram

of the abbey itself, S and Croix

intertwined above a moon, the

symbol of the city’s setting

as a port on the bend of a

river.

Dom Bedos also designed the

stone gallery, whose graceful

undulations mould the Positif's

towers as they project into

space. The undulating pattern

of the stone is doubly

underlined: first of all, the

fine fiuting which runs all

along the edge of the

relieving arch rises and

swells, below the Positif,

right up to the horizontal

ledge of the gallery, as if

the pipes were continued or

reflected in a stone organ; in

addition, the section of the

gallery’s ledge between this

fluting and the Positif

is gilt-coated. The undulating

motif is taken up and

multiplied by the painted

bands on the top and bottom of

the various towers. The

undulation of the gilded lines

deployed across the breadth of

the Grand orgue, at

the foot of the pipes, further

amplifies the gilded motif, and

provides a well-balanced base

for the thrust of the great

silvery pipes towards the

vault.

Below the gallery, the quoins

of the massive surbased arch

present a sculpted décor

consisting of trophies of

musical instruments garlanded

with ribbons and branches. On

the balconies that surmount

them, the black wrought-iron

railings, in High Louis XV

style and featuring on the

central medallions, in gilt, a

crossed pair of crosiers and

the abbey’s cross, frame the Positif:

they are probably the work of

the most remarkable ironsmith

of the Bordeaux area, Blaise

Charlut of La Réole, and it is

thought that they date from

around the same time as the

organ’s installation in the

abbey in 1756 - highly

decorated rocaille art gave

way around 1754 to a style of

greater sobriety which

retained only the flexible

contours of the preceding

fashion.

In a final round of major

renovations of the church in

1753, evidently related to the

building of the monumental

organ (and to the prosperity

of Carbonnieux), the rib

vaults in the nave were

rebuilt and large windows were

opened in its walls.

Subsequent nineteenth-century

modifications have left little

trace of the changes that were

made to the interior

decoration of the church at

this time, with the obvious

exception of the organ and its

gallery. Although the

redecoration of the choir

carried out after 1750 has

been removed, a few of its

elements still remain: the fine

wrought-iron communion rails

in the apse chapels; the

gilded wood statue of the

Virgin of Seafarers, a Virgin

in majesty, holding the Infant

Jesus in her arms and

trampling a serpent underfoot;

two large angels bearing

torches, brilliant ornaments

associated with great

ceremonies; a tall holder for

the Paschal Candle; two tables

in rocaille style, in gilded

wood topped with pink marble;

and a polychrome high altar in

pink and green marble, the

work of Italian sculptors. Nor

should one omit mention of the

impressive polychrome Christ

in lime wood, nearly four

metres high, shaven-headed and

poignant in expression, which

is thought to date from the

fifteenth century. This

splendid work, which combines

emotional power with elegance,

must certainly also have been

part of the devotional

material in the Baroque

period.

Francis

Lippa, October 2001

Translation: Charles

Johnston

|

|

|

|