|

|

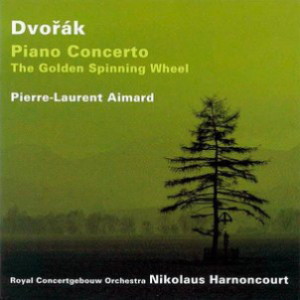

1 CD -

8573-87630-2 - (p) 2003

|

|

| Antonín

Dvořák (1841-1904) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Piano Concerto in G minor,

Op. 33 |

|

39' 29" |

|

- Allegro agitato

|

18' 23" |

|

1

|

| - Andante sostenuto |

9' 34" |

|

2

|

| - Allegro con fuoco |

11' 22" |

|

3

|

| The Golden Spinning Wheel,

Op. 109 |

|

28' 21" |

4

|

|

|

|

|

| Pierre-Laurent

Aimard, pianoforte |

|

| Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Het

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam (Olanda) -

20-26 ottobre 2001

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

live (Op.

33) / studio (Op. 109)

|

| Producer

/ Engineer / Assistant / Digital

editing |

Martina

Gottschau / Friedemann Engelbrecht /

Michael Brammann / René Möller

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

Classics - 8573-87630-2 - (1 cd) - 67'

52" - (p) 2003 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

"Stepchildren

Together"

Antonin Dvořák is

both

a very popular and highly

esteemed composer. However,

among his

many works are some which rarely

appear on concert programs and

which many people once used to

regard as less accomplished.

The Piano Concerto Op. 33, Dvořák's

only concerto for this

instrument, and the symphonic

poem The Golden

Spinning-Wheel both

belong to this group. And both

were performed

- if at all - in arrangements

made by others, who saw

themselves as ardent champions of

the

composer's music. They were

determined to "save" the

controversial works which they

considered as fundamentally

brilliant but imperfectly

executed.

In the

piano concerto, one can

already feel Brahams's aura in the

triplet passage of the

orchestral introduction, which is

reprised in

the coda of the first movement

Dvořák

wrote the concerto in 1876,

at around the time when he was

becoming internationally

recognized. Unlike nearly

every other composer of piano

concertos in

the 19th-century

- the

only exception worth

mentioning is Tchaikovsky,

whose concertos

were also

subjected

to arrangements - Dvořák

was not a concert pianist. He

only played the piano in

public in performances of

chamber works; indeed, he

wrote tne piano part of his

concerto as if it actually

were chamber music and did not

have to

struggle to make itself heard

over a full orchestra. Just as

in Brahms's Opus 15, the piano

is "symphonically" integrated

into the activity, even if Dvořák

gives nis soloist a cadenza,

in contrast to his later

concertos

for violin and violoncello. In

the finale, Dvořák

introduces a passionate

secondary theme, but then

refuses to "pump it up"

into an apotheosis à la

Grieg and Tchaikovsky at the

end of the

movement.

Long after Dvořák's

death, the pianist Vilém Kurz (1872-1945),

who taught at the

Prague Conservatory, decided

to thoroughly

revise tne solo part of the

concerto. His student Rudolf

Firkušný

(1912-1994), who was

the standard-setting

interpreter of the Dvořák

concerto for many years, later

made more changes of his

own. Kurz and Firkušný

gave the piano part not only a

more effective form, but also

revised it

in such a way that the parts

emerged more clearly. They did

not change one note in the

orcnestral part. The

arrangement is no longer in

use today, but not because it

is weak -

solely because it is not

authentic Sviatoslav Richter

seems to have been the first

great pianist to champion a

return to the original. Even Firkušný

started playing

the original version in his

later years, albeit without

absolute consistency.

Owing to his

friendship with Brahms, Dvořák

was considered as belonging

to his "party," meaning that

he was an unconditional

supporter of absolute

instrumental music. As a one-time

Wagnerian, however, Dvořák

did not feel comfortable

being pegged as a "little

Slavonic Brahms," even

though this epithet was

applied less by Brahms

himself than by the master's

disciples, such as Eduard

Hanslick. Dvořák

tried to break out of

this categorization,

particularly through his

sojourn in the United States

between 1892 and 1895. For Hanslick,

it was nothing less than a

catastrophe when Dvořák

returned from New

York with a new

self-awareness, said goodbye

to the symphony and the

string quartet, and devoted

himself to the symphonic

poem. But at the latest

since Dvořák's

Overture

to Othello Op. 93 (1892),

Hanslick

should have known that Dvořák

had no cornpunctions about

casting extra-Musical

contents - in this case,

Shakespeare`s eponymous

drarna - into a purely

orchestral musical form,

even though the composer had

still shied

from using the genre

designation "symphonic poem"

back then. Conversely,

although the "progressive

party" of

the "New Germans," which

passionately advocated

program music, had been

founded by Franz Liszt (who

always considered himself Hungarian

and not German), it began at

the time of Richard Strauss

to yield to a musical

chauvinisrn that even

prevented it from taking

non-German music seriously.

Consequently, Dvořák

fell

between two stools with his

four

symphonic poems on ballads

from the collection Kytice

(Bouquet) by the Czech poet

Karel Jaromír

Erben (The Water Goblin,

The Noon Witch, The

Golden Spinning.Wheel

and The Wild Dove).

Only among his fellow countrymen

did he find approval. They

also had no objections

against the literary sources

which were decried

as too bloodthirsty abroad -

perhaps not entirely without

reason.

Erben's ballad

The Golden Spinning-Wheel

(Zlatý

kolovrat in Czech)

relates the following

story in

63 five-line stanzas:

a king loses

his way in the woods and meets

a lovely

maiden

named

Dornička

whom he wishes to take as his

wife. Dornička's

stepmother

and stepsister

sever \he girl's arms and

legs

and put out her eyes. They

then store away the eyes and limbs.

The king falls

for the

trick and

marries Dornička's

stepsister. Then he goes off

to war. During his

absence, the false wife

acquires

a golden spinning-wheel from a

misterious dealer for the price of

the arms,

legs

and eyes of Dornička.

Upon his triumphal return, the

king asks for the spinning-wheel

to be shown to him. But

just like the flute in Gustav

Mahler's Das klagende Lied,

the

spinning-wheel unexpextedly

begins to sing

about the murder. In the meantime,

the

wizard has put together

the eyes, arms and legs of

Dornička's

mutilated body and awakened

her to new life.

The king rushes into

the woods and finds Dornička

unscathed. The proper wedding is

now celebrated, and the

stepmother and sister are

killed the same way that they

once killed Dornička.

Compared with the other three

Erben

ballads used as a literary

source by Dvořák,

The

Golden Spinning-Wheel is

exceptional in that the evil

deed is reversed by a

miracle.

A peculiarity of Dvořák's

symphonic poems is the way in

which the literary source is

transposed into music. In The

Golden Spinning-Wheel,

for example, we find

many passages where

the text could be

underlaid word

for word. The horn theme at

the beginning not only

suggests the approach of the

king on his horse, but it also

reproduces the rhythm of

the first two lines of the

ballad: "Okolo

lesa pole lán

/ hoj jede,

jede z

lesa pán"

("Near the woods is a large

field / hey!

from

the woods

a lord comes riding"). Dvořák

subjects the themes and motifs

derived in this manner to a

multiplicity of

transformations after the

fashion of

Liszt. But while in the other

symphonic poems based on

Erben's ballads he sought to

bring the episodes into

conformity with traditional

musical forms (sonata iform and

rondo),

in The Golden

Spinning-Wheel he

chooses the literary source as

his one and only guideline.

With respect to its formal

shape, the result is one of

the most radical symphonic

poems ever written. And in

their assumption that the

linguistic character of the

source must inevitably find

its adequate expression in the

music through such a direct

transposition, Czech authors

then and now

have praised Dvořák's

symphonic poems for their

unparalleled "Czechness."

Experiments, of course,

stimulate protest, and even

advocates of program music

have repeatedly voiced their

perplexity with this work.

It has been said, for example,

that the passages which can be

regarded as instrumentally

transposed dialogues could

only have a meaning if the

text were actually made audible.

The same applies to several

repeats. Dvořák's

son-in-law,

the composer Josef Suk

(1874-1935), thus made a great

number of cuts in The

Golden Spinning-Wheel.

It was

the only work by his father-in-law

which he submitted to such a

treatment.

Albrecht

Gaub

Translation:

Roger

Clement

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|