|

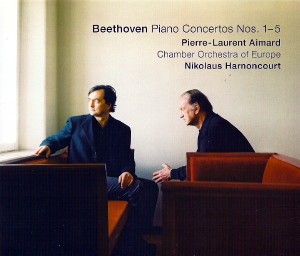

3 CD -

0927-47334-2 - (p) 2003

|

|

| Ludwig van

Beethoven (1770-1827) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Piano Concertos Nos. 1-5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Piano Concerto No. 2 in B

flat major, Op. 19 |

|

31' 10" |

|

- Allegro con brio

|

15' 35" |

|

CD1-1 |

| - Adagio |

9' 05" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - Rondo: Allegro molto |

6' 28" |

|

CD1-3 |

Piano

Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15

|

|

39' 14" |

|

- Allegro con brio

|

19' 13" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - Largo |

10' 58" |

|

CD1-5 |

- Rondo: Allegro

|

8' 55" |

|

CD1-6 |

| Piano Concerto No. 3 in C

minor, Op. 37 |

|

37' 50" |

|

- Allegro con brio

|

17' 58" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Largo |

10' 21" |

|

CD2-2 |

- Rondo: Allegro

|

9' 29" |

|

CD2-3 |

| Piano

Concerto No. 4 in G major, op. 58 |

|

35' 27" |

|

- Allegro moderato

|

19' 37" |

|

CD3-1 |

- Andante con moto

|

5' 28" |

|

CD3-2 |

| - Rondo: Vivace |

10' 20" |

|

CD3-3 |

| Piano Concerto No. 5 in E

flat major, Op. 73 |

|

39' 42" |

|

- Allegro

|

21' 05" |

|

CD3-4 |

- Adagio un poco moto

|

7' 33" |

|

CD3-5 |

- Rondo: Allegro, ma non

troppo

|

10' 56" |

|

CD3-6 |

|

|

|

|

| Pierre-Laurent

Aimard, Pianoforte |

|

| Chamber Orchestra

of Europe |

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Stefaniensaal,

Graz, (Austria):

- 23-26 giugno 2001 (Op. 15)

- 28-30 giugno 2000 (Op. 37)

- 26-28 giugno 2002 (Op. 58)

- 21-24 giugno 2002 (Op. 73)

Musikverein, Vienna (Austria):

- 21-23 novembre 2001 (Op. 19)

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer / Assistant /

Co-ordinator

|

Friedemann

Engelbrecht / Miichael Brammann / Julian

Schwenkner (1,3,4,5), René Möller (2),

Martin Aigner (3) / Martina Gottschau

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

Classics - 0927-47334-2 - (3 cd) - 70'

24" + 37' 50" + 75' 09" - (p) 2003 - DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

"Without the

pianoforte he would not have been

able to build a career for himself" - on

Beethoven's Piano Concertos

With his words about

Beethoven receiving "Mozart’s

spirit from the hands of Haydn," Count

Waldstein proved that he truly had a gift

for finding the

immortal turn of phrase.

Indeed, few

phrases have secured a more prominent

place in music

history than the one entered by

Waldstein in

Beethoven's "album amicorum." Just

before his young protégé

left on

his long journey

to Vienna in fall 1792,

the court wrote: "With

the help of assiduous

labor you shall receive Mozart's

spirit from the hands of Haydn."

Beethoven took lessons from Joseph

Haydn for just over a

year, and although it is

hard to tell just

what the 22-year-old actually obtained

from his teacher, it

was most probably

not "Mozart's

spirit." That such an original

composer as Haydn should pass on the

creative spirit of a much

younger colleague to one of his pupils

was more of a bold prophecy than a

realistic expectation

on the part of the count. For the

reality was apparently quite

different. When Haydn sent several of

his pupil's

compositions to "[His] Electoral

Highness” in Bonn

as evidence of the

lessons financed by the Bonn

administration, the Prince Elector

replied laconically "I

have received the young Beethoven's music

which you sent me with

your letter. But since he had already

composed and performed

such music - save for the fugue - here

in Bonn before

undertaking his

second journey to

Vienna, I

cannot regard this as proof of the

progress he has made in

Vienna."

At first glance,

the Elector was not entirely off the

mark. The first piano concerto that

Beethoven played in

Vienna, most likely in a private circle

at first, had already been sketched in

Bonn: the B flat major

Concerto, later published as the Piano

Concerto No. 2 Op.

19. A first version

- most of which is

lost today - was drafted around 1787/89.

The composer-pianist later revised the

concerto several times, always in

the context of one of his

public performances (the first closing

movement, the Rondo WoO 6, was

replaced by a new movement in

1794/95). Beethoven's

tenacious clinging to this concerto

suggests the profound interconnection

of his creative vision and his own

compositional achievements. For while

this concerto is still obligated in

many ways to the models laid down by

Mozart with respect to form, structure

and sound, it also explores new

dimensions which, of course, fully

disclose themselves only to the

analytical eye. It is above all in the

pensive, hymnic middle movement,

Adagio (with a cadenza-like passage

that bears the expressive marking "con

gran espressione"), that one senses a

new, “Beethovenian“

spirit.

The so-called "first" Piano Concerto

in C major showcases

the virtuoso talent of the pianist

Beethoven. Here the young composer

delved exemplarily into the pianistic

resources available at the

end of the 18th-century: bravura

writing, figurative interludes and

sparkling passagework are all wrought

with perfection in the three

movements. Beethoven, who had now

chosen Vienna as his home, premiered

the concerto during his first public

concert there in 1795. He played it in

the Hofburg Theater

on the evening of 29 March, as a kind

of “intermezzo” between the first and

second part of the oratorio Gioas

- Ré

di Giuda by the now nearly forgotten

Antonio Casimiro Cartellieri. The Wiener

Zeitung noted succinctly: "On

the first evening, the celebrated

Ludwig van Beethoven reaped the

unanimous acclaim of the public during

the interlude with a new pianoforte

concerto of his own invention." It is

worth noting that Beethoven was

already considered “celebrated” at the

age of 25! A few days

later, he played Mozart‘s Piano

Concerto in D minor K.

466 in Vienna, and in

December a new version of his B

flat major Concerto

under the direction of Haydn,

who took this occasion to present the

symphonic fruits of his London sojourn

to the Viennese public.

Even if the disconcerting catchword

about ”Mozart`s spirit from the hands

of Haydn”, can

hardly be understood as a vision of

"Viennese Classicism," the

names of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven

are unquestionably linked in a

singular manner in this series of

concerts held in 1795. When Beethoven

organized and held his own first

benefit concert in Vienna in April

1800, it was obvious that the names of

Mozart and Haydn could not be missing

from the program. The

broadsheet mentions "a large symphony

by the late Herr

Kapellmeister Mozart"

as well as an aria and

duet from Haydn's

oratono The Creation.

In addition to his own First

Symphony, Beethoven presented a "grand

concerto on the pianoforte"

at this lengthy concert, whereby it

remains unclear which of the two piano

concertos he played.

On 15 December 1800 Beethoven wrote to

the publisher Hoffmeister

in Leipzig to offer him the B flat

major Concerto

Op. 19, "which I really

do not consider one of my best, as

well as another [in C major

Op. 15], which will

be published by Mollo [...], because I

shall keep the better one for myself

until I make a tour." This "better"

concerto, which Beethoven reserved for

his own use, was the C minor Concerto

Op. 37. Even though one should not

uncritically agree with Beethoven’s

self-critical

assessment of the earlier B flat major

Concerto, his third concerto was

already regarded as a genuine

advancement of the genre by his

contemporaries. Its "style

and character [...] are

much more earnest and grand than those

of the two earlier pieces,"

opined Carl Czerny.

Alone the orchestral introduction of

the first movement, with its

tragic-heroic inflections, already

bursts all previous boundaries with

its 111 measures.

An idea that can be traced back to the

sketchbook of 1796 and that he

impressively realized here was that of

using the timpani in the cadenza ("for

the concerto in C minor, timpani at

the cadenza"). Yet in spite of its

great thematic, harmonic

and formal richness, Beethoven's only

minor-key concerto stands out above

all for its special

cyclical homogeneity; it is hardly by

chance that it was,

next to the E flat major

Concerto, the most popular of

Beethoven's concertos on 19th-century

concert programs.

In his final

two piano concertos

(in G major Op. 58 and in E flat major

Op. 73), Beethoven has the pianist enter

with apparent spontaneity at the very

beginning of the

work instead of letting him wait for

the end of the first orchestral

ritornello. Even if Beethoven did not

“invent” this (Carl Philipp Emanuel

Bach comes to mind, as well as

Mozart's “Jeunehomme”

concerto), this unusual opening

gesture immediately casts its spell on

the audience. The atmosphere of

improvisatory freedom also clearly

suffuses other parts of the G major

Concerto Op. 58, and from this

seemingly improvisatory feeling spring

the work`s originality and rousing

dramaturgy.

It was in his last

piano concerto, in the "Eroica"

key of E flat major,

that Beethoven most impressively

realized his ideal of a "symphonic

concerto." Just how

elegantly Beethoven brought out the

cyclical structure of the movements

can be seen above all at the close of

the central movement, which has been

“shifted” to B major. Here, after a

harmonic shift (B or C

flat is lowered to B flat, thus

becoming the fifth of E flat major),

the piano already anticipates the

rondo theme of the finale. Details of

this nature must have led the

reviewers of the Allgemeine

Musikalische Zeitung (1812)

to proclaim that this work was

"without a doubt one of the most

original, effective, but also most

difficult of all known concertos." In

any event, the underlying concept of

Beethoven's Plano Concerto No. 5 can

be grasped as a synthesis of the

experiences that Beethoven had made in

his preceding concertos - both from

the perspective of the genre itself as

well as of his own public

concertizing.

Beethoven used his own personally

organized benefit concerts to further

his career as a pianist and composer in

Vienna. His reputation

as an outstanding virtuoso had

preceded him to the imperial city

because of the close political

affiliations between Bonn and Vienna.

As a pianist, Beethoven quickly gained

access to the aristocratic salons. But

unlike the rather conventional,

elegantly brilliant playing of a

Hummel, Steibelt, Wölffl

or Gelinek, his playing reflected new

dimensions of expressiveness,

especially in his free improvisations.

Many years later, his pupil Carl

Czerny described this particular style

of playing as follows:

“Beethoven who arrived about 1790,

enticed entirely new and daring

passages from the pianoforte

through the use of the pedal and an

extraordinarily characteristic playing

which shone particularly in the strict

legato execution of chords, thus

constituting a new kind of song -

hitherto unimagined effects. His

playing did not possess the pure and

brilliant elegance found among many

other pianists, but it was sparkling,

grand and, especially in the Adagio,

highly emotional and romantic.

Just like his compositions, his

playing was a tone painting of the

highest order, calculated solely in

view of the overall effect."

Beethoven himself was fully aware of

his qualities as a composer and

pianist. In a letter of

April 1801 to the

publisher Breitkopf & Härtel,

he wrote: “Musical politics demands

that the best concertos should be

withheld from the

public for a time."

Beethoven thus protected his author's

rights by playing the concertos

exclusively himself; only

after a longer period of time were

they published. Incidentally, a

consequence of such “politics” was

that the C major

Concerto was published first. in 1801,

and thus called Piano Concerto No. 1,

even though it was

actually the second chronologically.

One has an idea of the extent to which

Beethoven improvised or played from

memory at his performances from a

letter to the publisher Hoffmeister,

in which Beethoven refers to the

belated printing of the B flat major

Concerto: "For instance, in the score

of my concerto, the

piano part, according to my custom,

was not written out, and I

have only just

done so; hence, to avoid delay, you

will receive it in my own, not very

legible, handwriting."

Nowhere is the interplay between the

pianist and the composer Beethoven as

palpable as in his piano concertos.

Significantly, he lost interest in

this genre when his growing deafness

forced htm to give up performing in

public. He was thus obliged to entrust

the performance of the last of his

piano concertos - the

one in E flat major - to his pupil

Czerny; he himself never played it in

public. (The cadenzas are no longer left

to the soloist's discretion

here: at the end of the first

movement, the composer expressly

instructs the pianist not to play his

- the

pianist's - own cadenzas!).

Nevertheless, sketches from 1815 show

that Beethoven was working on a sixth

concerto, which was destined to remain

incomplete. The lofty standards laid

down by the fifth concerto - in a

sense the "ne plus ultra" of the genre

- may well have

contributed to Beethoven's failure to

continue working on the D major

opening movement. In

any event, the piano concerto played a

very important role in the life and

works of Beethoven the composing

pianist or - depending

on the emphasis -

concertizing composer. The music

scholar Adolf Bernhard Marx

astutely recognized

this already in 1859 in his monumental

work on Beethoven: "Without the

pianoforte he would not have been able

to build a career for himself." And

without the genre of the

piano Concerio, an important part of

its foundation would have been

missing.

Wolfgang

Sandberger

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|