|

|

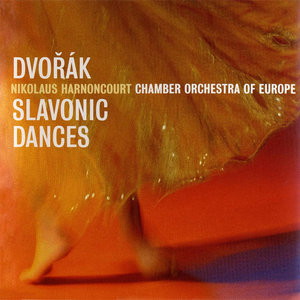

1 CD -

8573-81038-2 - (p) 2002

|

|

| Antonín

Dvořák (1841-1904) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Slavonic Dances, Op. 46 |

|

36' 59" |

|

| - No. 1 Furiant - Presto |

4' 08" |

|

1

|

| - No. 2 Dumka - Allegretto

scherzando |

5' 00" |

|

2

|

| - No. 3 Polka - Poco Allegro |

5' 22" |

|

3

|

| - No. 4 Sousedská - Tempo di

minuetto |

7' 15" |

|

4

|

| - No. 5 Skočná - Allegro

vivace |

3' 15" |

|

5

|

| - No. 6 Sousedská - Allegretto

scherzando |

4' 40" |

|

6

|

| - No. 7 Skočná - Allegro

assai |

3' 22" |

|

7

|

| - No. 8 Furiant - Presto |

3' 57" |

|

8

|

| Slavonic Dances, Op. 72 |

|

36' 13" |

|

| - No. 1 Odzemek - Molto

vivace |

4' 13" |

|

9

|

| - No. 2 Starodávný - Allegretto

grazioso |

5' 53" |

|

10

|

| - No. 3 Skočná - Allegro |

3' 36" |

|

11

|

| - No. 4 Dumka - Allegretto

grazioso |

5' 44" |

|

12

|

| - No. 5 Spacírka - Poco

adagio |

2' 39" |

|

13

|

| - No. 6 Starodávný - Moderato,

quasi minuetto |

4' 07" |

|

14

|

| - No. 7 Srbske Kolo - Allegro

vivace |

3' 22" |

|

15

|

| - No. 8 Sousedská - Lento

grazioso, quasi tempo di valse |

6' 39" |

|

16

|

|

|

|

|

| Chamber

Orchestra of Europe |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Stefaniensaal,

Graz (Austria) - giugno 2000 (Op. 72),

giugno 2001 (Op. 46)

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

studio

|

Producer

/ Coordinator / Engineer / Assistant

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Martina Gottschau / Friedemann

Engelbrecht / Michael Brammann / Julian

Schwenkner, Martin Aigner (Op. 72)

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

Classics - 8573-81038-2 - (1 cd) - 73'

23" - (p) 2002 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Emotion,

not sentimentality

On Nikolaus

Harnoncourt's

special

relationship with

the music of Antonín

Dvořák

"The

exuberant zest for life

and the tremendous

vitality that overwhelmed

the audience in the very

first bars of the Slovak odzemok,

which was played with

such-blooded ardour,

proved in fact to be

deceptive," we read in

one of the reviewa of

the Graz Styriarte

concert that forms the

basis of the present

live recording with the

Chamber Orchestra of

Europe. "Whit the second

of the eight Slavonic

Dances op. 72, a

paraphrase of a

Ukrainian dumka, the key

of E minor brought with

the mood of melancholy

that was to grow

increasingly sombre as

the evening progressed.

The result was an

interpretation not

satisfied with folklike

charm but keen to

explore the anbiguities

of this music and, as

such, able to move to

and fro beetween these

different levels of

expression with

admirable flexibility."

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt's decision

to begin performing Dvořák

works

in 1998 marked

a foray into

an area of the

repertory with

which few

people would

have

associated him

until then. By

this date in

his career, he

had, it is

true, already

delved deep

into the

19th-century

symphonic

repertory and

taken a keen

interest in

Mendelssohn,

Schumann,

Brahms and

even Bruckner,

but his

fascination with

Dvořák

came as

something of a

surprise -

perhaps even

to Harnoncourt

himself.

Yet

Harnoncourt

himself has

referred to

his

"underground

links" with

Slav music,

links that he

owes to

personal

experiences

and influences

and that turn

out to be

powerful

intellectual

amd emotional

forces. It

was with

almost

instinctive

assurance that

he gained

access,

effortlessly

and

convincingly,

to this highly

specific

musical

language, a

language

that sometimes

seems

deceptively

simple and

that all too

readily

misleads its

exponents into

relying

entirely on

rousing

effects. Even

in Dvořák's

most popular

works, he

succeeded in

going beyond

the familiar

clichés and

rediscovering

the great

composer who

was able to

invest his

thrilling

wealth of

ideas with a

strict sense

of form,

making

transparently

clear the

imposing

symphonic

structures

that sustain

these

intensely

colorful and

rhythmically

vibrant works.

Harnoncourt's

ability to

achieve all

this disturbed

only a handful

of Viennese

critics who

missed the

usual

barn-storming,

attention-grabbing

approach to

the Slavonic

Dances and

once again

felt obliged

to demand more

"charm".

For

all its

analytical

precision,

Harnoncourt's

approach Dvořák

is by no means

lacking in the

necessary

warmth and

vitality.

Rather, the

basic tone

that

characterises

these dances,

alternating

between

exultation and

meňancholia -

Harnoncourt

refers to it

as a "heavy

Slav tear" -

comes across

in an entirely

organic

manner, with

no false

pathos. This

is undoubtedly

due, not

least, to the

fact that

during his

years as

cellist with

the Vienna

Symphony

Orchestra,

Harnoncourt

was able to

assimilate a

tradition that

now seems to

have been

virtually

lost.

"When

I joined the

Vienna

orchestra in

the fifties,

"Harnoncourt

recalls," the

mother tongue

of sixty per

cent of the

musicians was

Czech. When we

travelled to

Czechoslovakia

with the

orchestra,

Czech was

spoken in the

orchestra from

the moment

that we

crossed the

border. And

when we played

Smetana's Má

vlast,

halft the

orchestra was

in tears. It

was incredibly

moving - all

these men with

tears

streaming down

their faces-

I, too, feel

something of

this emotion -

I don't want

to call it

sentimentality.

I played this

music lot at

that time, and

I always

enjoyed it. I

also remember

a remark by

Wolfgang

Sawallisch,

who said that

he should

really have

become a

cellist,

simply because

of the Dvořák

Cello

Concerto. For

such a

successful

conductor to

say that

impressed me a

lot."

For

the young

cellist

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt,

this concerto

was a source

of good luck

as it helped

him win the

place he

coveted in the

Vienna

Symphony

Orchestra. The

orchestra's

artistic

director was

then none

other than

Herbert von

Karajan, and

Harnoncourt

impressed him

so much at his

audition that,

out of a total

of forty

candicates, it

was he who was

immediately

taken on.

In

Harnoncourt's

view, it is

the

Austro-Hungarian

Empire's

legendary

cultural world

that forms the

background

against which

national

musical

developments

evolved in

Bohemia and

Hungary. "For

me, it's all

Austrian

music," he

says,

preferring in

this context

to quote the

Bible's

miraculous

"speaking in

tongues",

rather than

its famous

"Babel of

languages":

"What happened

on the day of

Pentecost is

something

miraculous,

something

unfathomable,

with everyone

speaking in

different

languages and

yet still being

able to

understand

each other.

This has quite

a lot in

commen with

art."

Against this

background,

the works by

Beethoven and

Schubert that

Harnoncourt

performs in

the concert

hall alongside

pieces by Dvořák

acquire

an extra

dimension. The

fact that folk

music can

inspire art

music has been

a

long-standing

Austrian

tradition

since Haydn's

day. Smetana

and Dvořák

were the first

composers to

bring out the

Slav element

as an

independent idiom,

and something

that still

seemed a

circumscribed

national

concern soon

acquired an

international

resonance and

an

international

following.

This

development is

particularly

clear from the

genesis of the

Slavonic

Dances. It was

in December

1877 that

Johannes

Brahms, in a

letter

to the Berlin

publisher

Fritz Simrock,

first drew

attention to

the talents

and financial

hardship of

the as yet

unknown Dvořák,

encouraging

Simrock to

commission the

Slavonic

Dances op. 46.

Their

publication

the following

year gave rise

to what one

contemporary

critic

described as a

"veritable run

on musi

shops", with

performances

of them taking

place in

Dresden,

Hamburg,

Berlin, Nice,

London and New

York within a

matter of

months. By the

time that Dvořák

had completed

the second set

in 1886 - they

were published

by Simrock and

performed for

the first time

in Prague in

1877 - he was

already an

internationally

acclaimed

composer.

Dvořák's

Slavonic

Dances do not,

of course,

contain in any

original folk

tunes of the

kind found in

Brahms's

Hungarian

Dances. As

Harnoncourt

stresses, Dvořák

used only

their rhythms.

"He was not

short of

inspiration of

his own: for

him, folk

music was very

important, of

course, and he

was fully

conversant

with it, but

it was no more

than a basis

for his own

invention."

Harnoncourt is

equally keen

to stress that

these are not

Bohemian

Dances, but

Slavonic

Dances, even

if the op. 46,

in particular,

is dominated

by Bohemian

dance forms

such as the

furiant,

polka,

sousedská

and Skočná:

Dvořák

deliberately

took in a

wider

geographical

area and

included not

only the

Ukranian

dumka, which

is represented

in both sets

of pieces, but

also the

Slovak odzemok

mentioned at

the beginning,

together

with the

Serbian kolo

and polonaise.

(These last

three types

appear only in

the op. 72

set.)

It

was in 1999

and 2000 that

Harnoncourt

first tackled

the two sets

of Slavonic

Dances. In

doing so, he

approached

them in the

thoughrful way

that

characterises

all his work,

thereby

avoiding the

beaten track

that so many

others have

followed. It

was with the

rarely played

Seventh

Symphony - Dvořák's

symphonic

masterpieces -

that he gained

access to the

composer's

world, before

deepening his

knowledge by

exploring the

unjustly

neglected

symphonic

poems in which

Dvořák

used the Czech

folk taled of

The Wild

Dove, The

Water Goblin,

The Noon

Witch and

The Golden

Spinning-Wheel,

turning them

into programme

music in the

very best

sense of the

term. These

symphonic

poems

represent the

culmination of

Dvořák's

later period

and are

perfectly

capable of

standing

comparison

with Richard

Strauss's

contemporary

tone poems.

Only

then was the

time right for

Harnoncourt to

tackle the

popular Eight

Symphony and

the Ninth, the

latter a piece

that has

almost been

played to

death. In this

way,

Harnoncourt

was able to

invest both

these works

with a new

symphonic

dignity.

"Rarely",

wrote one

critic of

Harnoncourt's

recording of

the Ninth,

"have I heard

this colossus

- invariably

watered down

programmatically

by other

conductors -

performed with

such symphonic

rigour and

architectural

unity. Rarely

has it seemed

so significant

a piece and so

free from the

senseless

clichés of

folk music.

Here we see

with total

clarity the

great

influence of

Beethoven as a

symphonist."

But

Harnoncourt

has not

completed his

reconnaissance

mission in

Bohemia's

woods and

fields: in the

autumn of 2001

he espoused

the cause of

an almost

forgotte early

work by Dvořák,

the G mino

Piano Concerto

of 1876. It is

to be hoped

that this

fascination

will now lead

him into the

world of Dvořák's

operas.

Monika

Mertl

Translation:

Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|