|

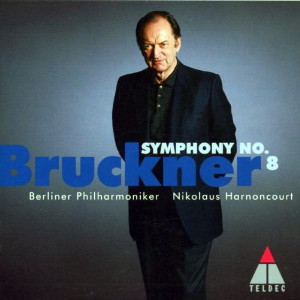

2 CD -

8573-81037-2 - (p) 2001

|

|

| Anton Bruckner

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 8 in C minor

(Nowak edition) |

|

82' 38" |

|

| - I. Allegro moderato |

16' 25" |

|

CD1-1 |

- II. Scherzo

|

14' 19" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - III. Adagio |

27' 22" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - IV. Finale |

24' 32" |

|

CD2-2 |

|

|

|

|

| Berliner

Philharmoniker |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Philharmonie,

Berlino (Germania) - aprile 2000 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

live

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Martina Gottschau / Friedemann

Engelbrecht / Michael Brammann /

Tobias Lehmann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

Classics - 8573-81037-2 - (2 cd) - 30'

43" + 51' 53" - (p) 2001 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

The

first performance of

Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony

in Vienna in December 1892

was brilliantly successful.

"A total triumph of light

over darkness," wrote an

enthusiastic Hugo Wolf. But

for the nearly

septuogenarian composer, the

triumph came almost too

late: this was the last

symphony that he was able to

complete.

By the time thot the work

was unveiled

by Hans Richter and the

Vienna Philharmonic at the Muikverein

in l892, it had already

undergone a series of

substantial revisions. In

the opening movement, for

example, Bruckner had

removed what had originally

been a fortissimo

ending. For the second

movement - a Scherzo - he

had written a new Trio. And

he had made a whole series

of other cuts and changes at

climactic

moments in the work. Above

all, however, he had revised

the instrumentation.

This revised version was

published in Leopold Nowak's

critical edition in 1955. It

is not, however, the version

that is generally known as

Bruckner's

Eighth Symphony today,

forthe version usually

performed in the concert

hall is the one published by

Robert Haas in 1939

and incorporating

characteristic passages from

the first version that are

inextricably bound up with

the work in the hearts and

minds of all who know the

piece.

Nikolaus Hornoncourt, too,

was initially af the opinion

that Haas's version came

closest to Bruckner’s

intentions. In the course of

an interview that he gave

early in April 2000 during a

playback of the recording

that he had made within the

framework of four concerts

with the Berlin

Philharmonic, he spoke of

the place occupied by the

Eighth Symphony in Bruckner's

late symphonic oeuvre and of the

conditions under which these

more than eighty minutes of

music can be made to make

sense for the listener - and

why he finally decided not

to wallow in the "purple

passages” of the score but

to follow the Nowak edition.

"The

first and second versions

are different attempts

to come to terms with the

same material," says

Harnoncourt. "In

the Eighth, unlike his other

symphonies, Bruckner did not

alter points of detail or

merely accede to the

requests of various

conductors, as he did, for

example, with the third

version of the Third

Symphony, where the message

is watered down. The Eighth

he radically altered on his

own initiative, ironing out

the tonal asperities -

which were undoubtedly

intended as such in the

first version - and altering

them in the direction of

what we generally call a

Wagnerian

sound. These may appear to

be small matters: in the

second version, for example,

he invariably writes for

triple instead of double

woodwind. But it is a

different principle of

instrumentation that is at

work

here, producing an

essentially different sound.

Each version creates its own

musical picture, which is

why I

do not think that they can

be mixed."

Harnoncourt sees the Eighth

Symphony as closely related

to the Seventh and Ninth

Symphonies. (The former he

has already recorded and the

latter he performed at a

memorable concert with the

Vienna Symphony Orchestra in

1999

that also included the

surviving sections of the

fragmentary final movement.)

"From the Seventh onwards,

Bruckner clearly felt that

everything belongs together

and so he used quotations

where he felt that he had

already said something

valid." And whereas the

Eighth is dedicated to the

Emperor Franz Joseph (the

emperor accepted the

dedication and paid for its

publication), the Ninth took

this a stage further and was

inscribed simply to "the

dear Lord".

In

terms of its overall

character, the Eighth is

clearly about death, an

aspect underscored by its key

of C minor. Harnoncourt

draws attention to many of

the allusions that underpin

this basic rnood. There is,

for example, no denying the

similarity between the

opening movement's first

subject and the Dutchman's

monologue -

also in C minor - from Act

One of Der fliegende

Holländer.

The opening movement also

includes an elaborately

concealed reminiscence of

Mozart's Requiem,

where a chromatically

ascending line in the bass,

beginning in bar 109

and extending over one and a

half octaves, necessitates

exactly the same harmonies

as those found in the "Quam

resurget".

But the main determining

element is the motif

described by Bruckner as the

"Todesverkündigung"

- the "Annunciation

of Death" - first heard in

the trumpets towards the end

of the opening movement's

development section (bar

255). Later, too, it remains

"very quiet", even when all

around it is fortissimo.

Towards the end of the

recapitulation, it is

repeated ten times,

surrounded by sighlike

figures in the woodwind, before

the coda

begins, bringing with it an

atmosphere that Bruckner

himself described both as a

"Totenuhr” - a clock ticking

away at a dying man's

bedside - and as an "act of

submission".

The "Annunciation

of

Death" permeates

the whole work. "The

piece is in tact written

around this upbeat motif,"

says Harnoncourt.

Of particular importance to

the conductor in this

context is the finale's

striking beginning, where

the last thing he wanted

is the so-called "Schusterstrich"

- a "cobbler’s

stroke" -

in the strings: "The Schusterstrich",

says Harnoncourt, "is

the usual form

of bow-stroke, but Bruckner

demands the exact opposite.

This is far

harder to play, but it makes

a big difference

as the short note is an

upbeat, not a downbeat and,

hence, not a stressed note."

Bruckner frequently

indicates the types of

bowing required and also

notes those passages that are

to be played on the G

string. "This produces a

very specific sound that is

free

ot overtones. Bruckner

himself was o very good

violinist. We did everything

exactly as he prescribed."

The virtuosic

freedom with which Bruckner

handled his thematic

material, coupled with the

work's vast dimensions, makes

the Eighth Symphony difficult

for interpreters to analyse

and for

listeners to tollow. In

Harnoncourt's opinion, a

coherent picture emerges

only if the conductor has

the clearest possible

overview of

the work's architectural

structure: "It is

like a vault in which every

stone has an

immutable function at a

particular point. I

need to have o clear idea of

that structure, then I

know exactly where I am.

You can compare it to the

great oratorios, where every

number is related to the

others. In Bruckner’s case

this isn’t always easy to

work out, but only in this

way does every movement

acquire its overarching

structure and the work as a

whole acquires its archlike

form, a form made up of

these individual movements."

At 709 bars in length, the

Eighth Syrnphony's final

rnovement is the longest

symphonic movement that

Bruckner ever wrote. As

such, it places great

demands on its interpreters.

"If

you look at just

the tempo markings: Slow -

Even slower - Tempo

primo. But what is 'tempo

primo'?

You have to create your own

tempo relationships. I can

grasp this logic by

indicating the different

tempo layers in the

diflerent score. There is an

incredible logic to it!"

Hornoncourt makes no attempt

to explain the whole-bar

rests and alien-sounding

chorale sections in this

final movement. Instead,

he draws on an image: "The

chorale interpolations with

their fermatas

are thematically

unrelated to the rest of the

movement. It

is as though Bruckner goes

off to pray from time to

time. He has set off on a

long journey

and

cannot complete it without

first having said

his prayers."

Monika

Mertl

Translation: Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|