|

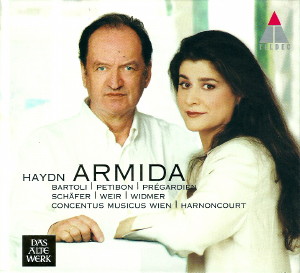

2 CD -

8573-81108-2 - (p) 2000

|

|

| Franz Joseph

Haydn (1732-1809) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Armida, Hob. XXVIII:12 |

|

128' 04" |

|

Dramma

eroico in tre atti - Libretto: Nunziato

Porta

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sinfonia |

|

5' 42" |

CD1-1 |

| Atto Primo |

|

48' 52" |

|

| -

Recitativo: "Amici, il fiero Marte" -

(Idreno, Armida, Rinaldo) |

1' 05" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - Aria:

"Vado a pugnar contento" - (Rinaldo) |

5' 09" |

|

CD1-3 |

| -

Recitativo: "Armida, ebben, che pensi?" -

(Idreno, Armida) |

0' 41" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - Aria: "Se

dal suo braccio oppresso" - (Idreno) |

3' 37" |

|

CD1-5 |

| -

Recitativo accompagnato: "Partě Rinaldo" -

(Armida) |

3' 13" |

|

CD1-6 |

| - Aria: "Se

pietade avete, oh Numi" - (Armida) |

6' 28" |

|

CD1-7 |

| - Marcia |

1' 06" |

|

CD1-8 |

| -

Recitativo accompagnato: "Valorosi

compagni" - (Ubaldo) |

1' 53" |

|

CD1-9 |

| - Aria:

"Dove son? Che miro intorno?" - (Ubaldo)

... Recitativo accompagnato (Ubaldo) /

Recitativo (Clotarco, Ubaldo) |

5' 46" |

|

CD1-10 |

| -

Recitativo: "Ah, si scenda per poco" -

(Zelmira, Clotarco) |

1' 14" |

|

CD1-11 |

| - Aria: "Se

tu seguir mi vuoi" - (Zelmira) |

3' 32" |

|

CD1-12 |

| -

Recitativo: "Della mia fede" - (Rinaldo,

Armida, Ubaldo) |

2' 45" |

|

CD1-13 |

| -

Recitativo accompagnato: "Oh amico! Oh mio

rossor!" - (Rinaldo, Armida) |

3' 42" |

|

CD1-14 |

| - Duetto:

"Cara, sarň fedele" - (Rinaldo, Armida) |

8' 43" |

|

CD1-15 |

Atto Secondo

|

|

43' 33"

|

|

| -

Recitativo: "Odi, e serba il segreto" -

(Idreno, Zelmira) |

0' 50" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Aria: "Tu

mi sprezzi, e mi deridi" - (Zelmira) |

3' 35" |

|

CD2-2 |

| -

Recitativo: "No, non mi pento" - (Idreno,

Clotarco) |

0' 32" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - Aria:

"Ah, si plachi il fiero Nume" - (Clotarco) |

4' 13" |

|

CD2-4 |

| -

Recitativo: "Va pur, folle" - (Idreno,

Ubaldo) |

1' 17" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - Aria:

"Teco lo guida al campo" - (Idreno) |

3' 22" |

|

CD2-6 |

| -

Recitativo: "Ben simulati io credo" -

(Ubaldo, Rinaldo, Armida) |

2' 28" |

|

CD2-7 |

| -

Recitativo accompagnato: "Armida... Oh

affanno!" - (Rinaldo, Ubaldo) |

6' 34" |

|

CD2-8 |

| - Aria:

"Cara, č vero, io son tiranno" - (Rinaldo) |

5' 05" |

|

CD2-9 |

| -

Recitativo accompagnato: "Barbaro! E

ardisci ancor" - (Armida) |

2' 51" |

|

CD2-10 |

| - Aria:

"Odio, furor, dispetto" - (Armida) |

2' 01" |

|

CD2-11 |

| -

Recitativo: "Eccoti alfin, Rinaldo, reso"

- (Ubaldo, Rinaldo) |

0' 44" |

|

CD2-12 |

| - Aria:

"Prence amato, in questo amplesso" -

(Ubaldo) |

3' 01" |

|

CD2-13 |

| -

Recitativo: "Ansioso giŕ mi vedi" -

(Rinaldo, Armida, Ubaldo) |

1' 10" |

|

CD2-14 |

| - Terzetto:

"Partirň, ma pensa, ingrato" - (Armida,

Rinaldo, Ubaldo) |

6' 42" |

|

CD2-15 |

| Atto Terzo |

|

29' 57" |

|

| -

Recitativo accompagnato: "Questa dunque č

la selva" - (Rinaldo) |

6' 11" |

|

CD3-1 |

| - Aria:

"Torna pure al caro bene" - (Zelmira) |

4' 18" |

|

CD3-2 |

| -

Recitativo accompagnato: "Qual tumulto

d'idee m'eccita in seno" - (Rinaldo) |

1' 06" |

|

CD3-3 |

| - Aria:

"Ah, non ferir: t'arresta" - (Armida) |

3' 53" |

|

CD3-4 |

| -

Recitativo accompagnato: "Che inopportuno

incontro!" - (Rinaldo, Armida) |

3' 35" |

|

CD3-5 |

| - [Presto:

"Oh Dio! Dove mi trovo?"] - (Rinaldo) |

2' 18" |

|

CD3-6 |

| - Aria:

"Dei pietosi, in tal cimento" - (Rinaldo)

... Recitativo accompagnato: "Ed io

m'arresto?" - (Rinaldo) |

3' 19" |

|

CD3-7 |

| - Marcia |

1' 03" |

|

CD3-8 |

| -

Recitativo: "Ho vinto" - (Rinaldo, Ubaldo,

Armida, Idreno, Zelmira) |

1' 20" |

|

CD3-9 |

| - Finale:

"Astri che in ciel splendete" - (Armida,

Zelmira, Idreno, Rinaldo, Ubaldo) |

2' 54" |

|

CD3-10 |

|

|

|

|

Cecilia Bartoli,

Armida (Soprano). maga al

servizio del principe delle

tenebre

|

|

Christoph

Prégardien, Rinaldo

(Tenore), cavaliere dell'esercito

cristiano

|

|

| Patricia Petibon,

Zelmira (Soprano), figlia del

sultano d'Egitto, stregata da

Armida |

|

Oliver Widmer,

Idreno (Basso), re dei Sareceni

|

|

| Scot Weir, Ubaldo

(Tenore), comandante dell'esercito

cristiano |

|

Markus Schäfer,

Clotarco (Tenore), comandante

dell'esercito cristiano

|

|

| Language coach:

Marta Lantieri |

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (with original

instruments)

|

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violin |

-

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violin |

-

Max Engel, Violoncello |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violin |

-

Dorothea Guschlbauer, Violoncello |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violin |

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violin |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Violone |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violin |

-

Robert Wolf, Transverse flute |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violin |

-

Reinhard Czasch, Transverse

flute |

|

| -

Annette Bik, Violin |

-

Hans-Peter Westermann, Oboe |

|

| -

Thomas Fheodoroff, Violin |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe |

|

| -

Annelie Gahl, Violin |

-

Herbert Faltynek, Clarinet |

|

| -

Sylvia Walch-Iberer, Violin |

-

Georg Riedl, Clarinet |

|

| -

Barbara Klebel, Violin |

-

Milan Turkovic, Bassoon |

|

| -

Veronica Kröner, Violin |

-

Eleanor Froelich, Bassoon |

|

| -

Annemarie Ortner, Violin |

-

Hector McDonald, Horn |

|

| -

Elisabeth Stifter, Violin |

-

Georg Sonnleitner, Horn |

|

| -

Irene Troi, Violin |

-

Andreas Lackner, Natural trumpet |

|

| -

Lynn Pascher, Viola |

-

Herbert Walser, Natural trumpet |

|

| -

Johannes Flieder, Viola |

-

Martin Kerschbaum, Timpani |

|

| -

Ursula Kortschak, Viola |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo |

|

| -

Gertrud Weinmeister, Viola |

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Musikverein,

Vienna (Austria) - giugno 2000 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Martina Gottschau / Martin Sauer

/ Michael Brammann /

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

Classics "Das Alte Musik" -

8573-81108-2-2 - (2 cd) - 54' 34" + 74'

30" - (p) 2000 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

"My

best wotk to date"

Joseph

Haydn is best known today as a

pioneering, composer of quartets and

symphonies, the first fully to

appreciate the potential of these new

genres in the middle of the eighteenth

century. But, for much of his life,

Haydn himself considered that his

operas were far more irnportant than

his instrumental music. In part, this

was due to the perceived status of

opera and instrumental music at the

time. Italian opera, in particular,

was the most international of forms

and, if a composer like Haydn wanted

to claim wider significance, he had to

demonstrate his abilities in the opera

house. Instrumental music, on the

other hand, was not yet as esteemed;

it ivas to be Haydn’s unselfconscious

role to raise the status of the

symphony, the quartet and instrumental

music generally to the same level as

opera. For more mundane reasons, too,

Haydn would have been prompted to

value his operas more than his

instrumental music, because for 25

years, from the mid-1760s to 1790, the

form virtually dominated his existence

as a composer.

Haydn was employed as Kapellmeister to

the Esterháry family, the richest and

one of the most influential

aristocratic families in the Austrian

monarchy. Like many such families they

had a palace in Vienna, in the

Wallnerstraße, and a principal

residence iri the countryside, in

Eisenstadt, some 28 miles south-east

of Vienna. Haydn served under four

successive princes, the most

extravagant of which was the second,

Prince Nikolaus, known as "the

Magnificent". Shortly after assuming

the title in 1762 Prince Nikolaus

Esterházy began the ambitious project

of converting a small hunting lodge in

marshy terrain near Ödenburg (Sopron)

in Hungary into a sumptuous summer

palace, formally named after the

family, Eszterháza, and soon dubbed

the Hungarian Versailles. The project

took nearly twenty years to complete

and was notable not only for the

wealth and ostentation of the various

buildings but for the way that the

unpromising terrain was transformed

into magnificent park-land.

While several aristocrats in the

Austrian territories frequently

presented small-scale performances of

operas, usually in makeshift theatres,

the extravagance of Nikolaus’s love of

music prompted him to build two fully

equipped opera houses on either side

ofthe main palace at Eszterháza, one

for Italian opera and one for

marionette theatre (performed in

German). From 1776 onwards, a

permanent fulltime company was based

at the court, which must have been one

of the most isolated companies in

Europe. When the Italian opera house

burnt dovvn in 1779 Nikolaus promptly

ordered it to be rebuilt and it was

reopened two years later.

As Kapellmeister, Haydn was

responsible for the smooth running of

these two opera houses, helping to

select the repertoire, adapting

existing operas for performance,

composing his own operas, rehearsing

the singers and orchestra, and

directing performances from the

harpsichord. Most of the repertoire at

the maim opera house was by the

leading composers of the day, Anfossi

(1727-97), Cimarosa (1749-1801),

Paisiello (1740-1816), Piccinni

(1728-1800), Salieri (1750-1825) and

Sarti (1729-1802), with Haydn himself

composing eleven maior works between

1766 and 1784. Armida was the

last opera Haydn composed for

Eszterháza, first performed on 26

February 1784. A few days later, full

of enthusiasm, he wrote to his

publisher, Artaria, in Vienna:

"Yesterday my

Armida was performed for the

2nd time. It's said that it’s my best

work to date." Indeed, it turned out

to he the most frequently performed

Haydn opera at the court, with a total

of 54 performances over the next few

years; it was also produced at the

private opera house of the Erdödy

family in Preßburg (Bratislava) in

1786, in Pest (Budapest) in 1791, and

in Turin in 1805.

Although the opera company at

Eszterháza had a director, a full

complement of singers and orchestral

players, a team of designers, painters

and copyists, supplemented, as

necessary, by the part-time assistance

of other Eszterházy employees, rather

unusually it did not have a full-time

poet. As a result, Haydn was never

able to profit from the sustained

artistic collaboration that Mozart,

for instance, enjoyed with Lorenzo da

Ponte. Indeed, none of Haydn’s operas

for Eszterháza sets a text specially

written for the composer; instead, all

were based on existing librettos,

sometimes quite old ones, adapted by

local poets.

The subject matter of Armida, the

Saracen sorceress, and her love forthe

Christian knight, Rinaldo, ultimately

comes from Torquato Tasso’s famous

epic poem Gerusalemme liberata,

completed in 1575. In the eighteenth

century the story featured in both

French opera (Lully and Gluck) and

Italian opera (Handel, Salieri and

Cherubini). The immediate source for

Haydn’s libretto was an opera, Rinaldo,

by Antonio Tozzi, first performed in

Venice in 1775. It, in turn, was a

hybrid version that fused two separate

librettos based on the story, the

first written by Durandi and set to

music by Anfossi (Turin, 1770), the

second written by De Rogati and set by

Jommelli (Naples, 1770). Although it

was destined to be Haydn’s last opera

for the Eszterháza court it was also a

new challenge for him. With the

exception of two short works, Acide

and L'isola disabitata,

Haydn’s operas had all been comic

ones; Armida was his first

full-length serious opera. He began

composing it in the summer of 1783; at

the same time, Travaglia (the resident

designer) began planning the costumes

and elabotate sets, including a

throne-room, mountainside, a garden, a

dark forbidding woodland and open

countryside with a distant view of

Damascus. It was one of the most

ambitious works produced at Eszterháza

requiring, in addition to the expected

complement of singers and players, a

stage band (with clarinets, the first

time Haydn had used the instrument in

a major work) and over three dozen

actors dressed in Roman and Turkish

costumes.

Haydn’s music has a similar sense of

scale and ambition. Comprising three

acts, this opera employs six singer,

with a predorninance of high voices

(two sopranos, three tenors and only

one bass) and a basic structure of

secco recitative alternating with

bravura arias. The first aria, "Vado a

pugnar contento" sung by Rinaldo, is

typical of the enthusiastic manner in

which Haydn responds to operatic

convention; a standard aria di

guerra (war aria) it

superimposes a full sonata form on the

old da capo structure, uses

the orchestra to create an excitable

military atmosphere and suggests the

heroic valour ofthe protagonist

through declamation, virtuosity and,

towards the close, a cadenza.

Eighteenth-century commentators on

opera frequently complained that

dramatic continuity and plausibility

were too readily sacrificed to

displaying the virtuosity of

individual singers. Haydn seems to

have been aware of these concerns and,

to prevent this work from being a

collection of enthralling conceit

arias, he elides many numbers into the

following one, especially in Acts II

and III, discouraging disruptive

applause and promoting dramatic

continuity.

From his earliest operas for the

Esterházy court Haydn had revealed a

striking ability to evoke natural

phenomena in music - storms,

bird-song, moonlight, even

stomach-ache - and to a far greater

extent than is normally found in

contemporary Italian opera. The

lengthy second scene of Act III, over

25 minutes of continuous music, is set

in a forbidding forest in which the

conflicting demands of love and duty

are played out by the leading

characters, Armida and Rinaldo - a

mixture of unreal atmosphere and

personal torment that anticipates a

major obsession of German Romanticism.

The initially unthreatening calm of

the woods is well caught in Haydn's

music, using the standard pastoral

images of murmuring streams and bird

calls, including the dove that was to

feature in The Creation and

the chirping quail that was to

reappear in The Seasons and,

even more famously, in Beethoven's

Pastoral Symphony. A lengthy solo for

flute and bassoon over triplet rhythms

- a texture often found in Gluck's

operas - accompanies the gentle

cavorting of Zelmira and her allendant

nymphs as they urge Rinaldo lo yield

to his feelings. Equally reminiscent

of Gluck is the music that follows

Armida's angry departure and the entry

of the Furies.

Eighteenth-century opera, whether

serious or comic, usually ends

positively with a united declaration

of the moral lesson implied by the

evening's entertainment. The most

significant of the changes that were

made to the libretto at Eszterháza -

whether at Haydn's instigation cannot

be judged - is the removal of the

contrived happy ending that had

featured in Tozzi’s opera in favour of

something more sinister. To the sound

of martial music and, in the theatre,

tne sight of a marching army,

Rinaldo's mixed emotions are still

apparent while Armida, for her part,

is consumed by vengeance.

David

Wyn Jones

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|