|

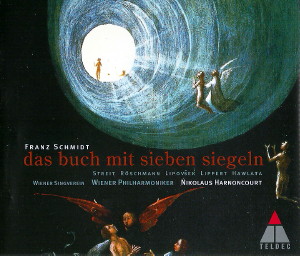

2 CD -

8573-81040-2 - (p) 2000

|

|

Franz Schmidt

(1874-1939)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln -

Oratorium aus der Offenbarung

des Heiligen Johannes |

|

116' 42" |

|

| für Soli, Chor, Orgel

und Orchester |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Prolog |

|

30' 34" |

|

| - Moderato: "Gnade sei mit euch"

- (Johannes) |

3' 18" |

|

CD1-1 |

| - Andante: "Ich bin das A und

das O" - (Die Stimme des Herrn) |

3' 08" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - Vivace: "Und eine Tür ward

aufgetan im Himmel" - (Johannes) |

4' 49" |

|

CD1-3 |

| - "Heilig, heilig ist Gott der

Allmächtige" - (Die vier lebenden Wesen,

Johannes, Die Ältesten) |

5' 59" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - "Und ich sah in der rechten

Hand" - (Johannes, Engel) |

6' 17" |

|

CD1-5 |

| - Andante un poco lento: "Nun

sah ich, und siehe, mitten vor dem Throne"

- (Johannes, Chor, Soloquartett) |

7' 03" |

|

CD1-6 |

Erster

Teil

|

|

36' 27" |

|

| - Lento - (Orgelsolo) |

3' 14" |

|

CD1-7 |

| - "Und als das Lamm der Siegel

erstes auftat" - (Johannes, Chor) |

2' 23" |

|

CD1-8 |

| - "Und als das Lamm der Siegel

zweites auftat" - (Johannes, Krieger,

Frauen) |

7' 22" |

|

CD1-9 |

| - "Und als das Lamm der Siegel

drittes auftat" - (Johannes, Der schwarze

Reiter, Tochter und Mutter, Frauen) |

4' 24" |

|

CD1-10 |

| - "Und als das Lamm der Siegel

viertes auftat" - (Johannes, Zwei

Überlebende) |

4' 10" |

|

CD1-11 |

| - "Und als das Lamm der Siegel

fünftes auftat" - (Johannes) |

1' 00" |

|

CD1-12 |

| - "Herr, du heiliger und

wahrhaftiger" - (Chor) |

3' 25" |

|

CD1-13 |

| - "Und es wurde ihnen einem

jeglichen gegeben" - (Johannes, Die Stimme

des Herrn) |

2' 36" |

|

CD1-14 |

| - "Und ich ah, daß das Lamm der

Siegel sechstes auftat" - (Johannes, Chor) |

7' 54" |

|

CD1-15 |

Zweiter

Teil

|

|

44' 42" |

|

| - Vivace ma non troppo -

(Orgelsolo) |

3' 02" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Sempre ritardando - Lento:

"Nach dem Auftun des siebenten der Siegel"

- (Orgelsolo, Johannes) |

9' 20" |

|

CD2-2 |

| - "Im Himmel aber erhob sich ein

großer Streit" - (Johannes) |

6' 41" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - Lento: "Und als die große

Stille im Himmel vorüber war" - (Johannes) |

1' 37" |

|

CD2-4 |

| - Allegro, ma maestoso: "Die

Posaune verkündet großes Wehe" -

(Soloquartett, Chor) |

9' 10" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - "Vor dem Angesichte dessen" -

(Johannes) |

2' 57" |

|

CD2-6 |

| - Lento: "Und ich sah einen

neuen Himmel" - (Johannes, Die Stimme des

Herrn) |

6' 40" |

|

CD2-7 |

| - "Hallelujah!" - (Chor) |

5' 15" |

|

CD2-8 |

| Epilog |

|

4' 59" |

|

| - "Wir danken dir, o Herr" -

(Männerchor) |

2' 08" |

|

CD2-9 |

| - Moderato: "Ich bin es,

Johannes, der all dies hörte" - (Johannes,

Chor) |

2' 51" |

|

CD2-10 |

|

|

|

|

| Kurt

Streit, Tenor (Johannes) |

|

| Dorothea

Röschmann, Soprano |

|

| Marjana

Lipovšek, Contralto |

|

| Herbert

Lippert, Tenor |

|

| Franz

Hawlata, Bass (Die Stimme

des Herrn) |

|

|

|

| Wiener

Singverein / Johannes Prinz, Chorus

Master |

|

| Herbert

Tachezi, Organ |

|

| Wiener

Philharmoniker |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Musikverein, Vienna (Austria)

- aprile 2000 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Wolfgang Mohr / Martina

Gottschau / Friedemann Engelbrecht /

Michael Brammann |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec Classics - 8573-81040-2

- (2 cd) - 67' 01" + 49' 41" - (p) 2000

- DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

a plea

for a masterpiece

|

It

was shortly before Easter 2000 that

Nikolaus Harnoncourt first conducted

Franz Schmidt’s oratorio Das Buch

mit sieben Siegeln with the

Vienna Philharmonic in a performance

that aroused widespread public

interest. Here, after all, is a piece

that remains controversial not least

on stylistic grounds: its music, which

reflects the spiritual upheavals of

the interwar years, is open to

misinterpretation, with superficial

observers claiming that it is

reactionary. Written between 1935 and

1937, it was premièred by the Vienna

Symphony Orchestra at the city’s

Musikverein in June 1938, only months

after the Anschluß, when Austria was

annexed by Hitler’s Germany. So

monumental a work naturally attracted

the attention of the Nazi regime, as a

result of which the composer himself

later fell into disrepute, even though

he died in February 1939, before the

outbreak of the Second World War.

Surprising though Harnoncourt's

decision may seem to take this work

into his repertory, Das Buch mit

sieben Siegeln has in fact been

familiar to him since his youth. In

the late forties the director of music

at Graz Cathedral, Anton Lippe,

organised a performance with the Graz

Cathedral Choir, of which the

Harnoncourt farnily were members -

all, that is, apart from Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, who always preferred his

own individual pursuits. Even so, he

gained a clear impression of the work

from the numerous rehearsals that were

held at home: “My mother and brothers

and sisters had great difficulty

pitching the intervals, and so my

father rehearsed it with them at the

piano. It was something of a family

event. And in the ears of my father

and, hence, of the rest of the family,

this was the epitome of avant-garde

music. Never again did they penetrate

as deeply into the world that lies

beyond the confines of traditional

harmony.”

Later, during his years as cellist

with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra,

Harnoncourt himself took part in a

number of performances of the work

under conductors such as Anton Heiller

and Josef Krips. “I never really got

to the bottom of the piece. The cello

has a lot to play in it, and I can’t

say that I ever gained a real overview

of either its form or its content. But

it‘s one of the pieces that has always

moved me. I’ve always seen it in a

direct line of succession with the

great oratorios that for me begin with

Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 and

include Mozart’s C minor Mass, Haydn’s

Harmoniemesse, Beethoven’s Missa

solemnis and Brahms’s German

Requiem. All these pieces go

beyond the framework of the liturgy

and grant us an entirely new insight

into sacred music. And Schmidt was the

first person to set the words of the

Apocalypse in a comprehensive way."

For Harnoncourt, the result is “an

incredible setting of an incredible

text", the work of a composer whose

genius is beyond question. Yet our

perception of it is distorted by all

manner of prejudices and clichés, with

the result that Schmidt’s stature

remains to be rediscovered by our own

generation today.

a Charismatic personality

“You had only to come into the

briefest contact with Schmidt and you

were already musical,” one of the

composer’s many pupils described his

particular charisma. Schmidt was a

popular and influential figure on the

Viennese musical scene, a gifted

teacher who taught a whole generation

of young musicisans and also a

talented pianist- in spite of his firm

convinction that the piano ruins

a musician's ear. As a creative

musician he was able to offer

impressive accounts of the great works

of the piano repertory without any

special technical training. Having had

lessons as an adolescent with the

famous teacher Theodor Leschetizky, he

hated five-finger exercises. In this,

he offended against the prevailing

etiquette in matters of piano

technique, yet he was an acclaimed

interpreter in the concert hall and

radio studio, as well as being

lionised in Vienna's salons. In 1914

he took over a piano class at the

Vienna Academy of Music and went on to

write a number of works for the

pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who had

lost his right arm in the First World

War.

Schmidt‘s formal training was on the

cello. Following his final examination

at the Vienna Conservatory in 1896 he

even wrote a cadenza for Haydn’s D

major Cello Concerto, earning Brahms‘s

personal accolade in the process. He

went on to join the Vienna

Philharmonic and the Vienna Court

Opera Orchestra. This was the period

when Gustav Mahler was director of the

Vienna Opera. A blend of respect and

animosity conditioned their mutual

dealings and gave rise to frequent

conflict. Mahler valued Schmidt as a

cellist and regularly used him in

preference to the official first

cellist, Friedrich Buxbaum, leading to

violent tensions within the orchestra,

but he refused to stage Schmidt’s

opera Notre Dame. For his

part, Schmidt admired Mahler as a

conductor but found his symphonies

“cheap”.

Schmidt resigned from the Vienna

Philharmonic in 1911 in order to spend

more time composing, and three years

later he gave up his post with the

Court Opera Orchestra, but remained on

the staff of the Academy of Music.

From 1922 he also taught composition

and in 1927 he even became its

director, a position he hoped to use

to obtain a teaching post for Arnold

Schoenberg. When the idea was turned

down by the Ministry of Education,

Schmidt organised a concert of

Schoenberg‘s works in token of his

high regard for his fellow composer.

Even though he himself was

temperamentally unresponsive to

atonality, he admired Schoenberg for

what he described as the aural

equivalent of far-sightedness and is

known to have studied his Harmonielehre.

revered and reviled

Franz Schmidt was born in Preßburg

(now Bratislava) in 1874. At that date

the kings of Hungary were still

crowned in the city’s cathedral. His

father was a shipping agent of

German-Hungarian extraction. His

mother was Hungarian. It was she who

gave him his first piano lessons. As a

child, he is said to have heard Liszt

play. He studied harmony and the organ

with a Franciscan friar in Preßburg -

“on the side and completely

effortlessly”. He was fourteen when he

and his family moved to Vienna. His

training at the Conservatory began two

years later, in 1890. He even signed

up to Bruckner‘s class, but in the

event the class did not take place.

Alongside Bruckner, it is Brahms and

Dvořák who are generally regarded as

his compositional models.

Schmidt was a thoroughbred musician of

the old Austrian school who came to

maturity at a time of radical upheaval

that brought fundamental changes with

it. Contemporaries report that Alban

Berg thought very highly of Schmidt’s

music. Yet today’s commentators often

dismiss him as a traditionalist,

deriding his musical language as

reactionary and eclectic, a

preconceived opinion that probably

derives from the disparaging views of

the contemporary critic (and Mahlerian

advocate) Richard Specht. And a number

of leading performers of a later age

have been taken in by this view, with

Herbert von Karaian, for example,

refusing to conduct Das Buch mit

sieben Siegeln on the grounds

that it is an example of “late

Romanticism".

For Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Franz

Schmidt is one of the few figures in

the history of music whose gifts he

would describe as exceptional: Schmidt

developed his own completely

independent musical idiom and in this

way was entirely abreast of his times.

“It’s an absolutely unmistakable

personal style, and for me there is no

question that Schmidt helped to shape

the course of 20th-century music. I do

not feel qualified to tell such great

artists how they should develop. If an

individual chooses not to follow

Schoenberg, he can in all honesty

still be a magnificent composer. And

it is not just Das Buch mit sieben

Siegeln that I consider so

fascinating, but his other works as

well.”

Schmidt’s work-list includes two

operas (Notre Dame, 1902-4, and

Fredigundis, 1916-21), four

symphonies that were written at

considerable intervals in time between

1896 and 1933 and a whole series of

organ works and chamber pieces. But

only Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln

has found a lasting place for itself

in the repertory, a position it owes

not least to its dedication to

the Gesellschaft der

Musikikfrunde in Vienna, whose

Singverein has ensured a seamless

performing tradition at least within

Austria itself. Nikolaus Harnoncourt

was happy to avail himself of the

Singverein`s experience in performing

this complex work. It was the first

time that he had worked with this

famous Viennese chorus, which is made

up entirely of amateurs.

The role of the Evangelist is regarded

as one of the most challenging in the

tenor repertory on account of its

range and the fiendish difficulties

that it involves. Schmidt wrote it for

a Heldentenor, but lyric tenors such

as Julius Patzak were later considered

ideal for the part, “Schmidt‘s

intimates - in other words, Josef

Krips, Anton Heiller and Anton Lippe -

regarded his original casting as a

mistake,” says Harnoncourt. “The Saint

John of the première was a failure as

a Heldentenor. Schmidt would certainly

have changed it. Perhaps he did so,

and it is only the printed score that

remains uncorrected.” A light, lyric

voice, as in the present recording,

will not be a problem if the vast

orchestral forces are appropriately

handled, and it is also preferable in

bringing out the expressive nuances in

the score.

between two world Wars

“As far as I know," wrote Schmidt in

his foreword to his oratorio, “mine is

the first attempt at a comprehensive

setting of the Apocalypse. When I

first approached this enormous task,

it immediately became clear that I

could do so only if I found a form for

the text that retained its essential

wording, while reducing the literally

unmanageable dimensions of the work to

a size that could be grasped by the

average human brain.”

Schmidt achieved this end in a

remarkable way, Harnoncourt argues. “I

find it really unusual for a composer

to change so little - especially with

so vast a subiect - in order to impose

his own particular form on it. The

words are largely taken from Luther‘s

translation of the Bible and edited by

Schmidt. Of course, he omitted certain

things, changed the order of others

and added some of his own. But these

additions are really quite minimal. It

wouldn’t be wrong to say that he stuck

very close to his source.”

On completing his Fourth Symphony,

Schmidt began to cast around for a

libretto for his next work. But why

did he choose the Book of Revelation,

with its tremendous images of the

destruction of humankind, rather than

the text that his friend, the

Philharmonic oboist Alexander

Wunderer, had written for him? Was it

mere chance, or did Schmidt feel a

need in the mid-1930s to respond to

this particular section of the Bible

and to do so - as he himself puts it

in his foreword - “from the standpoint

of a profoundly religious man and also

as an artist”?

During his career as a cellist,

Harnoncourt remembers meeting a number

of musicians who knew Schmidt

personally. As a result, he is in no

doubt about the depth of the

composer‘s religious feelings. Given

the passage of time, it is scarcely

possible to say any longer who drew

his attention to the Apocalypse and

why he used Martin Luther‘s

translation. His pupils and friends

knew only that he was looking for a

dramatic subject.

Harnoncourt believes that a decisive

factor in Schmidt’s choice was the

archaic power of the text: "There‘s a

tremendous fascination to this world

of images. And as someone who lived

through the first third of the century

and experienced it with peculiar

intensity, Schmidt undoubtedly saw how

the political situation was worsening.

There really was the feeling that a

boil was about to burst at this time,

people felt they were living on a

volcano. But it was in the air: he was

writing between two world wars and

composing a work that reflects what it

is like to live on the edge of a

volcano. He described its contents as

a "fight against evil". It reminds one

of Freud‘s oneiric visions. I think he

meant the evil ,within us all."

“Of all the books in the New

Testament, the Apocalypse is for me

the one most like a book from the Old

Testament. With our European logic

we’re simply not able to relate to the

world of oriental imagery. But I don’t

interpret it literally. When it says

in the Old Testament that Abraham is

prepared to kill his own son, the idea

it expresses is that an extreme

measure must be taken. And when the

four Horsemen of the Apocalypse appear

in the Book of Revelation, I take that

to mean that we have a world at our

disposal and that we’re doing

something terrible with this wonderful

opportunity. The events of the

apocalypse can also be interpreted to

mean the individual's struggle with

himself."

At this point it may be instructive to

recall Schmidt's own personal

situation. In 1932 he suffered a

severe blow with the death of his

daughter Emma. He himself was

seriously ill for some considerable

time and he was in an extremely poor

physical state when, following an

operation, he set to work on Das

Buch mit sieben Siegeln. Even at

that date he must have been aware that

time was running out for him. Das

Buch mit sieben Siegeln was to

be the culmination of his lite’s work.

thrilling imagess in sound

Schmidt’s oratorio falls into two

sections, with a framing prologue and

epilogue. Formally and stylistically,

it is an extremely complex work. Even

though the orchestra “does not play a

dominating role” (to quote Schmidt

himself), the tremendous choral

writing is complemented in a decisive

way, with the instrumental writing

underscoring the message ofthe text.

“Schmidt is a real man of the

orchestra,” says Harnoncourt. “You can

tell this from the ways in which he

adds dynamics to the individual

voices. If he had regarded the

orchestral writing as no more than an

accompaniment for the chorus, this

complexity would not be necessary.

After all, there is also the organ,

which at several points provides a

solo commentary on the action. I

actually think that the resources are

perfectly balanced.”

In the musical account of the forces

of nature at the opening of the sixth

seal, for example, in the raging storm

and the fugue that depicts the

oppressively rising floodwaters,

contrapuntal mastery and a real

feeling for tone colour combine to

create thrilling images in sound.

A key scene that Schmidt entrusted to

the orchestra is Michael’s fight with

the dragon at the start of the second

section, following the scene depicting

the Redeemer‘s birth, which is

characterised by echoes of Christmas.

Harnoncourt‘s working notes are worth

quoting here: “The orchestral writing

gradually becomes more independent and

describes a wild and complex struggle.

Various groups of instruments and

rhythmic structures embody the

different combatants. The harmony

dissolves. The defeated dragon

continues its fight with the woman’s

remaining progeny. The battle between

good and evil is now fought out on

earth. Complicatedly vivid orchestral

writing in which the struggle is

expressed in inversions and strettos

that grow increasingly dense, gaining

in speed and intensity and leading to

the victoriously radiant Vivace in

4/4-time. The C or D major that is

expected here is not reached, instead

the B flat major fanfare casts

something of a pall over the victory

celebrations.”

stylistic complexity in a period of

change

Within itself, the piece is

characterised by extreme contrasts.

“Schmidt offsets the threefold entry

of the Voice of the Lord with the

Horsemen of the Apocalypse, the

natural disasters and the seven

trombones,” says Harnoncourt in his

analysis of the work. “The seven

trombones proclaim the seven sorrows.

It is all interconnected, held

together by a trombone theme.”

(Luther’s translation refers to

“trombones” at this point and Schmidt

duly writes for trombones, but the

Authorised Version of the Bible

describes these instruments as

trumpets.)

The fact that this trombone episode

begins in C minor and ends in C major

is no doubt a musical topos,

Harnoncourt admits, but he refuses to

see it as a superficial effect and

leaps to Schmidt’s defence,

energetically rejecting the

oft-repeated charge that the composer

used a whole number of stylistic

devices in an eclectic manner. The

piece undoubtedly uses a lot of

different stylistic devices, but at

this point in the history of music

composers simply had at their disposal

a palette extending over several

centuries. They also used others -

think, for example, of the various

directions taken by Stravinsky. It‘s

simply there. In his German

Requiem, Brahms likewise offers

a recapitulation of all that existed

in his own day, lust as Beethoven did

in his Missa solemnis.

“You also have to remember that

there‘s a dialogue between what

happens in the concert hall and what

is written into the score. When

Schoenberg or Bartók wrote music, they

did so for listeners who listened to

the programmes current at that time.

Schmidt was still rooted in the

pre-war period. But this was an age

when first performances were gradually

becoming less interestingthan

revivals. The first performance of a

Bruckner symphony was still far more

important than a repeat performance of

something else. This changed only

duringthe first decades ofthe 20th

century - except for Richard Strauss

and Puccini.”

The theory that,

consciously or otherwise, Schmidt

produced a great synthesis of the

entire German music tradition from

Bach to Wagner and, shortly before the

outbreak of the Second World War,

created a vision of the decline of

that tradition is one that Harnoncourt

accepts only with reservations: “There

may be something to this view,” he

says, “but from Bach to Wagner strikes

me as too narrow. In terms of its

content, the work’s stylistic position

is very clearly defined. Schmidt

operates within various stylistic

spheres depending on the ideas that

have to be depicted. This also

includes the Second Viennese School,

with whose representatives he was,

after all, in very close contact.

“Naturally I see this work in the

tradition of late Romanticism. I have

the feeling that some people are

hysterically pro-Schmidt, while others

are equally hysterically against him,

I really can't understand why he

produces such a violent reaction. If

it’s not based on the quality of his

work... If it were really

eclectic and backward-looking, people

wouldn't get so worked up over it. My

view is that Das Buch mit sieben

Siegeln is a masterpiece. This

is what counts for me.”

Monika

Mertl

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|