|

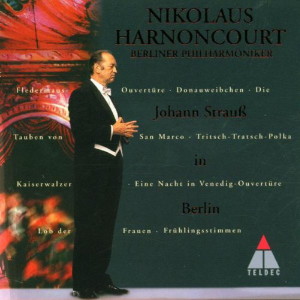

1 CD -

3984-24489-2 - (p) 1999

|

|

| Johann

Strauss (Sohn) (1825-1899) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - "Kaiserwalzer", Op.

437 |

12' 16" |

|

1

|

| - Ouvertüre "Eine Nacht in

Venedig" (Berliner Urfassung) |

7' 36" |

|

2

|

| - "Die

Tauben von San Marco" Polka

Française, Op. 414 |

4' 33" |

|

3

|

| - "Frühlingsstimmenwalzer",

Op. 410 |

7' 11" |

|

4

|

| - Ouvertüre "Die Fledermaus" |

8' 56" |

|

5

|

| - "Seid

umschlungen, Millionen" Walzer, Op.

443 |

10' 08" |

|

6

|

- "Lob der Frauen" Polka

Mazur, Op. 315

|

3' 53" |

|

7

|

| - Simplicius-Walzer

("Donauweibchen"), Op. 427 |

9' 41" |

|

8

|

| - "Tritsch-Tratsch"

Schnellpolka, Op. 214 |

2' 31" |

|

9

|

- "Kaiser

Franz Josef I. Rettungs-Jubel Marsch",

Op. 126

|

3' 31" |

|

10

|

|

|

|

|

| Berliner

Philharmoniker |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Philharmonie,

Berlin (Germania):

- settembre 1998 (1,3,5,8,9)

- aprile 1999 (2,4,6,7,10) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

live

(1,3,5,8,9) / studio (2,4,6,7,10)

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Martina Gottschau / Friedemann

Engelbrecht / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

Classics - 3984-24489-2 - (1 cd) - 70'

37" - (p) 1999 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

The

Magic of Music Notation

Schubert, Johann Strauß

and Styrian Folksong

Many years ago I was

on a concert tour of the United States

when I met a solitary

instrument maker in a village miles

from nowhere. He told

me about a flute quartet that met

there every month and that had just

played “I bin a

Steirerbua“ (I'm a lad

from Styria) from a collection of

German folksongs, Der

Zupfgeigenhansl. He

sang it to me, and I was amazed

at the transformation that this old

familiar song had undergone in the

maple forests of New england:

although the

performers were convinced

they were reproducing the music

note-perfect, I could hear an American

Puritan swing behind the notes of my

muchloved song. It was almost

impossible to recognise it arty

longer. Once again I was forced to

realise that the sort of music

notation that is second nature to me

with its lines and dots and circles is

simply impossible to

read when it comes

with no instructions and the user has

no idea what it means.

Dividing a note-value into minims,

crotchets and quavers - or into

triplets and so on - may produce

arithmetical divisions,

and may even be done in good faith;

but the result is a monotonous

metrical drone or the jeu perlé

of many pianists that fills me with

feelings of fear bordering on panic

and that confuses identical cultured

pearls with their multiform natural

counterparts. In genuine folk music,

be it from Styria, Bavaria, Hungary,

Romania or wherever, the most complex

rhythms are reproduced by very simple

people with absolute assurance; but

this is also the source of art music,

and it is entirely possible, not to

say probable, that Bach, Mozart and

Beethoven would be just as shocked

by the way we interpret their music as

I myself was shocked by my

little song.

Schubert and Johann Strauß are the

only echt Viennese composers

of international stature. Both of them

naturally assume that musicians will

understand their "language", which is

the musical dialect of Vienna. The

rhythmic subtleties,

the deviations from what is metrically

notated (metre and rhythm are by no

means the same), and the breaks and joins

in the melodic line cannot be

expressed in notes: you have to know

and understand and love them. -

Naturally, all the little “tricks” and

dialectal nuances in performance tend

to become more and more pronounced

from one generation to the next: what

was originally a tiny pause in the Fledermaus

Waltz is now interpreted as a

noticeable break and said to be "echt

wienerisch"- but

not, I hope, today. And the

famous “oom-pah-pah" -

or, as the Viennese say, “ess-tam-tam”

- in a waltz

accompaniment is a thing of great

delicacy whose rhythms resemble the

complex pounding of the

heart. To perform it is simple,

but not at all easy! The second beat

should be a little too early, but if

it is, then it really

is too early.

Tradition is something that is handed

down from generation to

generation, but each time it is passed

on, a little mud sticks to it. When I

arrived in Vienna after the wart,

there were still many players in the

great orchestras whose fathers had

perforrned in Strauß's

band. Today's players

are their grandsons and

great-grandsons. Strauß

was keen that his waltzes

should not be played too quickly: the

thrilling sense of momentum that

sweeps you along with it was to come

from a sense of calm

motion. But recent fashions have

changed all this. And there is now

also a tendency to ignore the element

of melancholy that is such an integral

part of even Strauß's most

carefree-seeming music.

And how much rnore difficult it is to

tap in to the roots of

Schubert's Viennese character,

something that goes much further back

in time and that is additionally based

on the curiously sad dance tunes that

Schubert is believed to have played so

wonderfully well on the piano. Smiles

and tears in Schubert and Strauß,

but with the emphasis inverted.

Strauß

was everywhere loved and wanted, and

Berliners, too, were captivated

by this expression of the Viennese way

of life, with its sophisticated blend

of the world of the intellect and that

of feeling. He had already visited the

city on a number of occasions to

conduct concerts (for

the first time with

his own orchestra

in October 1852), and his operetta A Night

in Venice had been premièred here in

October 1883 (the Pigeons of San

Marco Polka comes from this

work, and the brilliantly brief

original “Berlin” version of the

Overture is receiving its first

performance here as the 20th century

draws to a close) when he was invited

to conduct a number

of his own works at the official

opening of the "Königsbau"

in 1889. Of the

100-strong

orchestra, he wrote to his

step-daughter, "Alicerl", that it "is

going through thick and thin with me.

[...] I'm conducting

with my little finger, I need only to

flash my eyes at them

and there’s no

holding them back.” Among the works

that he conducted at

his concert on 19

Octobee were the Overture to Die

Fledermaus, the Tritsch-Tratsch

Polka and the Simplicius

Waltz (published under the title Donauweibchen).

But the great sensation was

undoubtedly the first performance, on

21 October, of the

Emperor Waltz that he had written

specially for the

occasion. Originally called Hand

in Hand, it was

intended to celebrate the alliance

between the two emperors, Franz Joseph

and Wilhelm. that had heen reaffirmed

shortly beforehand in Berlin. The

piece was twice encored and

enthusiastically described in the

newspapers: "The Emperor Waltz begins

on a note of Prussian bellicosity, you

can literally see and hear Old Fritz’s

Guardsmen marching past -

but then [...]

everything again assumes an echt

wienerisch dash and verve.”

In short, all the works included in the

present recording are in some

way related to Berlin. The waltz Seid

umschlungen, Millionen was

written for the International

Exhibition of Music

and Theatre and dedicated to Strauß's

friend, Johannes Brahms, who returned

the compliment by prevailing on his

own publisher, Fritz Simrock, to issue

it. It was the respect

that Strauß

felt for its dedicatee that inspired

him to write the work in the first

place. It was, he

said, "spiced and seasoned without

forfeiting the aim of a waltz". Brahms

expressed his delight following the

first performance in Vienna's

Musikvereinssaal. The Kiser Franz

Joseph I. Rettungs-Jubel Marsch

(Emperor Franz Josef I

March of Rejoicing)

was Strauß's reaction

to the failed attempt to assassinate

Franz Joseph

on 18 February 1853. The quotation

from the Austrian national anthem, Gott

erhalte Franz den Kaiser (God

preserve the Emperor Franz), should

presumably be parsed as a past tense

here: God preserved the Emperor.

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

Translation: Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|