|

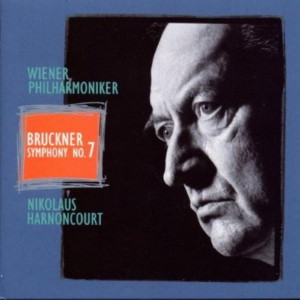

1 CD -

3984-24488-2 - (p) 1999

|

|

| Anton

Bruckner (1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 7 in E major

|

|

60' 01" |

|

| - I. Allegro moderato |

19' 10" |

|

1

|

- II. Adagio: Sehr feierlich und

sehr langsam

|

20' 48" |

|

2

|

| - III. Scherzo: Sehr schnell -

Trio: Etwas langsamer |

8' 53" |

|

3

|

| - IV. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht

zu schnell |

11' 09" |

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

| Wiener

Philharmoniker |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Musikverein,

Vienna (Austria) - giugno 1999 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

live

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Martina Gottschau / Friedemann

Engelbrecht / Michael Brammann /

Christian Feldgen

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

Classics - 3984-24488-2 - (1 cd) - 60'

01" - (p) 1999 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Anton Bruckner's

Seventh Symphony

|

Performed

for the first

time under Arthur Nikisch

at a Gewandhaus concert rn

Leipzig on 30 December 1884,

Anton Bruckner's Seventh

Symphony in

E major was the first

of the composer's symphonies

to win him immediate acclaim

and international

recognition, soon becoming known

not only

in

Europe but

even

as far

afield

as America.

By this stage in

hrs career, Bruckner was already

sixty and had been writing symphonies

for some twenty years. He

was now living in

Vienna, where he was the

regular butt of scornful and

devastating reviews on the

part of the city's leading

music critit, Eduard Hanslick,

whose antipathy towards

Bruckner was in

inverse

proportion to his friendship

for Brahms. As a result, the

great acclaim accorded to

the Seventh

Symphony in

Leipzig and elsewhere

was a novel experience for

Bruckner, but no less

delightful for

all that: "He stood there in his simple

clothes in front of the

excited crowd, bowing

again and again in his

helpless, awkward

manner," wrote the critic of

the Berliner Tageblatt

on 10 August

1885 after

a performance of the work in

the city. "Now a wistful smile

would

play

around the old man`s lips,

as though

the result of

effortfully suppressed

emotion, now a curious light

filled his eyes, and his

face - by no means

attractive, but sympathetic

and innocently

trusting - glowed with warm

and heartfelt pleasure."

Bruckner was

a slow

composer who spent almost

two whore years working

on his

Seventh Symphony and no

fewer than fourteen months

honing the opening

movement alone.

The autograph

score bears

witness to

the different

stages in

the

compositional

process. Generally Bruckner

wrote clearly, in

a clean and legible script,

but the score

Contains numerous revisions:

some

passages have been pasted

over, others havec been

erased and yet others

scraped away, thereby

offering a graphic picture

of the

composer's

evident need

to revise his

works. Yet he must have

regarded the Seventh

Symphony as

somehow

finisched, since

it

survives in only a single

version, unlike his other

symphonies - notably the

Third - which have come down

to us in a whole series of

often radically differing

versions. Only one passage

exists in divergent

recensions: bars 177-82 of

the Adagio. This passage

remains a bone of scholary

contention,

for it is unclear whether

the famous cymbal crash

and, with it, the timpani

and triangle, belong here

or not. According to Josef

Schalk, they were merely a

concession to Arthur

Nikisch, who conducted the

first performance and who

had asked the composer

to give greater emphasis to

the climax of the Adagio.

If this is so, they are not

really by Bruckner himself:

they are not an authentically

Brucknerian

idea.

On the other hand, Bruckner

noted down this brief

passage on a separate strip

of paper and added it to

the score, which he then

bequeathed to the Austrian

National Library. Was

this an oversight

on his part or was it

intentional?

Advocates of the

cymbal clash

argue that Bruckner could

have removed and even

destroyed the slip of paper,

which was

merely inserted

loosely

into

the score, if he had so

desired. The opposing

faction, by contrast,

prefers to adopt a more

puristic approach and rejects all

such additions,

drawing attention to a

(possibly inauthentic)

note added to the scrap

of papper, "gilt nicht"

(i.e., invalid), and

arguing that Bruckner

made this change only

because he was prevailed

upon to do so by a third

party.

The

introduction to the

Seventh Symphony is

typically Brucknerian,

with its string

tremolando preparing

the way for the first

subject which, at

twenty-one bars, is

arguably the longest

of any symphonic

subject written before

that date. By laying

the foundations fot

the main

theme, these

introductions are

among Bruckner's

most distinctive

features as a

composer. But no

less significant for

the overall

structure of his

individual symphonic

movements is a kind

of editing technique

particularly

noticeable in the

case of the second

subject, which

Bruckner was later

to use in his Te

Deum and which

has since become known,

in consequence, as the Te

Deum theme.

The

Scherzo is dominated

by a striking theme

on the trumpet

which, once again,

is entirely

characteristic of

the composer, with

its ascending

octave to e,

followed by a

descending fifth

to a

thrice-repeated o

(the first note

doubly dotted)

and, finally, by a

return to the

initial note.

Frequent

repetitions of

this theme ensure

that it becomes

ingrained in the

listener's memory.

The

final movement

is

surprisingly

succinct and,

apart from that

of the

"Nullte" (i.e.,

the Symphony

no. "0"), is

the shortest

of all

Bruckner's

finales. Here

the waves of

sound that

invariably

lead to the

orchestral

climaxes in

his music are

briefer and

more concise

than in any of

his previous

symphonies.

Bruckner's

Seventh

Symphony was a

success from

the very

outset - not

that this

persuaded the

single-minded

Hanslick, who

had his own

ideas of "the

beautiful in

music", to

take a more

favourable

view of

Bruckner's

compositional

style. For

him, the work

was a

"symphonic boa

constrictor"

of which he

could make

little sense.

It was

Bruckner's

organ playing

that first

brought the

two men

together, and

their initial

contacts seem

to have been

entirely

cordial. As a

composer of

sacred music,

Bruckner

earned

Hanslick's

respect, but

as soon as he

began to take

a serious

interest in

the field of

the symphony,

Hanslick

applied

different

standards, as

set forth in

his book On

the Beautiful

in Music:

as a form of

absolute

music, the

symphony

reigned

supreme, but

in order to

justify that

status it had

to meet

certain

criteria,

criteria that

Hanslick found

embodied in

Brahms's

symphonies,

but not in those

of Bruckner. As

a friend of

Brahms and an

opponent of

the New German

School (among

whose members

he wrongly

numbered

Bruckner on

account of the

latter's veneration

of Wagner), he

had little

choice but to

reject the

Austrian

composer's

works out of

hand. In

addition, he

had had to

give way to

Bruckner in an

interminable

tug-of-war

over the

question of a

teaching post

at the

University in

Vienna, a

circumstance

that seriously

affected

relations

between the

two men and

made it

impossible for

Hanslick to

adopt an

objective

attitude to

Bruckner's

works: he

could never

judge them

impartially.

Bruckner

suffered so

badly from

this rejection

that in the

wake of the

Seventh

Symphony's

successful

première in

Leipzig, he

wrote to the

Vienna

Philharmonic -

wich had

already given

the first

performances

of the Second,

Fourth and

middle

movements of

the Sixth

Symphonies - and

specifically asked them

not to perform the piece

"for

reasons that stem solely

from the deplorable local

situation

with regard to the

leading

critics, a situation

that could only detract

from the successes that

I

have recently enjoyed

in

Germany". None the less,

Hans

Richter conducted

the work at a

regular Philharmonlc

Concert in

the city on 21

March 1886,

when it

attracted conflicting

notices

on the part of Vienna`s

critics.

According

to Hanslick, the audience "put

up little

resistance;

some of them fled after

the second movement of

the symphonic

boa constrictor, and their

flight

turned to a fullscale

exodus following

the third

movement, so that only a

small band of

listeners

remained

to enjoy the

finale". But

even Hanslick

had to concede

that "this plucky legion

of

Brucknerians applauded

and cheered with the

fource of thousands.

There has certainly

never been an occasion

when a composer has been

called out on to the

platform four or five

times after every

movement". Although he

found the work

"unnatural" and

"inflated", Hanslick

admitted that he could

not judge it properly.

It is no wonder, then,

that Bruckner was so

terrified of Vienna's

critics. His fear is

immortalised

in countless

anecdotes, a number of

which have come down

to us in multiple

versions, suggesting

that they may contain

at least a kernel of

truth: on receiving

the Order of Franz

Joseph, Bruckner was

apparently asked by

the emperor what he

desired more than

anything else and is

said to have replied

to the effect that he

wanted the emperir to

stop Hanslick from criticising

his music. But even

without the

emperor's

intervention,

Bruckner was

eventually able to

triumph over his

critics.

Renate

Ulm

Translation: Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|