|

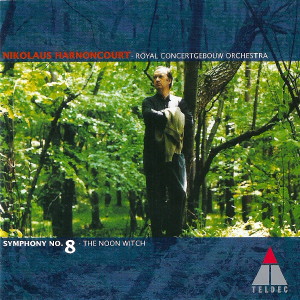

1 CD -

3984-24487-2 - (p) 1999

|

|

| AntonŪn

DvořŠk (1841-1904) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 8 in C major,

Op. 88 |

|

36' 32" |

|

- Allegro con brio

|

10' 47" |

|

1

|

| - Adagio |

10' 02" |

|

2

|

| - Allegretto grazioso |

6' 09" |

|

3

|

- Allegro ma non troppo

|

9' 31" |

|

4

|

| The Noon Witch "Polednice",

Op. 108 |

|

14' 09" |

|

| - Allegretto |

5' 44" |

|

5

|

| - Andante sostenuto e molto

tranquillo, |

3' 39" |

|

6

|

| - Allegro |

2' 08" |

|

7

|

| - Andante |

2' 39" |

|

8

|

|

|

|

|

| Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Het

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam (Olanda) -

dicembre 1998 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

live

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Martina Gottschau / Friedemann

Engelbrecht / Michael Brammann / Tobias

Lehmann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

Classics - 3984-24487-2 - (1 cd) - 50'

46" - (p) 1999 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

"To rethink

the works completely afresh"

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt in conversation with Klaus

DŲge on DvořŠk as a symphonist and

symphonic poet

Klaus DŲge: DvořŠk

is the third 19th-century composer

after Brahms and Bruckner whose works

you're now recording on an appreciable

scale. What draes tou to this

composer? And what is his attraction

for you as an interpreter?

Nikolaus Harnoncourt: I got to

know DvořŠkís music from an early age.

My father played the piano and we used

to perform DvořŠkís piano trios at home.

During my seventeen years as an

orchestral cellist, from 1952 to 1969, I

often played the three great symphonies

- the Seventh not so often, the Eighth

very often and the "New World" Symphony

several times a yeah. I was always very

moved by this music. But it annoyed me

that it was routinely dismissed as the

work of a lightweight composer. You

really canít reproach a composer for

drawing on such a profusion of ideas! I

think that DvořŠkís music has an immense

depth to it; it has a beauty,

melancholy, yearning, a typically Slav

valedictory mood and a sadness that are

characteristic of all Czech music. Itís

not sentimentality, but very profound

expression; and it`s music that can

easily come to grief. You have only to

allow the brass to play a little too

loudly and the whole musical texture is

reduced to a great harmonic mush, albeit

one that sounds quite splendid. But the

music contains a large number of

elaborate details, and I really canít

understand musicians who treat DvořŠk

like some hack composer who, they

concede, writes fantastic works of great

musicality but whom they still regard as

just a little inferior to the great

composers of his day.

This view of DvořŠk

has implications for the way in which

his works are routinely interpreted...

Yes, and the works that are most often

enlisted here are the Slavonic Dances.

But these pieces are difficult to play

well, and I'm not prepared to perform

them in the concert hall unless I have

enough rehearsals.With DvořŠk you pay a

high price for any untidiness and lack

of precision. My working method involves

rethinking works like the Eighth

Symphony and asking whether the dots

over the notes merely indicate that the

notes in question are not legato and, if

not, whether they should be long or

short, and what type of articulation

DvořŠk had in mind with this range of

staccato markings, from hammered marcato

to barely separated staccato cantabile.

As for the tonal balance, here too there

is a lot that needs careful

consideration when you've got three

trombones and a tuba, together with four

horns and two trumpets, pitted against a

woodwind department with a completely

different dynamic range and when you see

how meticulously DvořŠk differentiates

the dynamics: he doesn't write a

fortissimo for the full orchestra, but

always takes account of its weakest

member, so you can always tell that it

is the flute that has to play

fortissimo, while the other instruments

all have to play in such a way that the

flute can be heard and understood. I

have to say in this context that it is

very stimulating when one has enough

rehearsal time and can really rethink

these works completely afresh, bar by

bar.

Anyone listening to the Eighth

Symphony will find many sudden

insights, notably in the case of the

flute interjections in the second

movement. They sound more forced than

usual.

The flutes donít take up the musical

argument and carry it forward but are a

reaction to it. This is clear from the

fact that DvořŠk later entrusts these

outbursts to the strings, where

they become real fortissimo screams,

interrupting the melodic line. It`s as

though the imaginative world of the act

of composition, with its cut and thrust

of argument and counterargument, comes

alive here over and above the notes

themselves. I find this very pronounced

here.

Although the Eighth is DvořŠk's

second most popular symphony it is

also, in a sense, his most

controversial...

On account of its form.The doyen

ofViennese music critics, Eduard

Hanslick, said that it was fragmentary

and rhapsodical, while Brahms expressed

the view that it contained only

irrelevancies, but nothing of substance.

It is possible to see these remarks

against the background of their age, and

I`ve long been preoccupied by this

question. DvořŠk was undoubtedly

familiar with the norms of sonata form,

and in his early symphonies he took up

and developed a Schumannesque variant of

this form.That he now trumps it with

sovereign mastery, playing with it as a

composer, using it in a way quite

different from Brahms and genuinely

refashioning it means that, for me, he

succeeds in creating a convincing

original structure. Players have to be

made aware of this, otherwise all you

get is a kind of notesplnning that may

be very beautiful but which obscures the

novelty of the work. I felt this most

powerfully in the case of the final

movement, where, towards the end, a

great lyrical block arises as a variant

of the cello theme. Under this heading,

too, come the accelerandos in the codas

of the first and last movements, the

second of which brings the work to an

end almost in the manner of a waterfall.

The Eighth Symphony dates from

1889, when DvořŠk

no longer saw himself as an absolute

musician but, increasingly, as a tone

poet. The work must surely have been

affected by this development.

Iím convinced of it. The themes are so

eloquent. Even the introductory theme is

highly expressive as a result of its

suspensions, its gestural language and

its instrumentation. But the question

remains: did DvořŠk intend to convey to

his listeners a particular concrete

meaning, or was it not important to him

how listeners interpreted it? If the

player performs in what I might call an

eloquent manner and recognises the

work's marked rhetorical component, he

will play it differently, and the

audience will hear a much more

expressive piece. I have always been

interested in the language of music and

asked myself what are the rhetorical

figures in Bach's music and the

linguistic gestures in Mozartís. And

then suddenly I read that Beethoven says

that a musician who does not understand

rhetoric cannot compose. As a conductor

I want to have all the information I can

about the work I am conducting,

information both intrinsic and extrinsic

to the piece,and I also want the players

to share this information, because the

interpretation will be more convincing

as a result. But I do not think that

DvořŠk wanted to convey any concrete

information to the audience of the

Eighth Symphony. He was concerned,

rather, with universal expressive images

and chains of association that each

individual listener can experience for

him- or herself.

By contrast, the music of DvořŠkís

symphonic poem The Noon Witch

demands to be interpreted in concrete

terms...

When Mendelssohn writes a concert

overture about the tale of the fair

Melusine, he knows perfectly well that

there will not be a single person in the

audience who is not familiar with this

story. And when DvořŠk writes The Noon

Witch - first and foremost for his Czech

compatriots - he knows that everyone

will be familiar with Karel JaromŪr

Erbenís ballad and that even those

listeners who do not know Erbenís poem

in detail will at least be familiar with

the underlying story, just as we are

familiar with the story of Hansel and

Gretel. And if a composer writes a

symphonic poem called The Noon Witch, we

know very well that it will be about a

mother who threatens her screaming child

with the noon witch, until the witch

herself arrives and takes the child

away. Basically, it is a musical

exploration of the theme of guilt and

the way we come to terms with such

guilt.

Haw does DvořŠk

translate his programmatical

source into music? ls the

word-painting doggedly literal, as

music critics have often complained?

Sometimes he takes a line from the poem

- especially if it is exceptionally

striking - and uses it to create a clear

rhythm, an eloquent atmosphere. I mean,

it`s simply impossible for word-painting

to be as doggedly literal as it is with

Richard Strauss, for example. DvořŠk

never did anything like that. He

musicalises and dramatises the text: the

witch`s motif, for instance, first

appears at the start of the idyll, while

the child is playing games; in a way,

this turns the idyll on its head.Then

the witch arrives with the

recitative-like motif, ďGive me the

child". And then comes the dance.

Everyone can hear that this is a dance,

everyone knows the expression "witchís

danceĒ. And you can hear the hobbling,

hopping witch with her broomstick in the

woodwindsí sharply dotted rhythm, which

is heard in counterpoint to a variant of

the motif associated with the children's

screams, suggesting less of a triumph

than a desire to evoke a sense of terror

by purely musical means. This eerie

dance increases our fear that something

terrible is happening. I can well

understand what Leoö JanŠček meant when

he wrote that whenever he heard this

chromatic contrary motion he could

literally see the witch`s bony hand

reaching out to grab the child.

Musically speaking, I lind this

incredibly vivid, immediately

intelligible and really very very

powerful.

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|