|

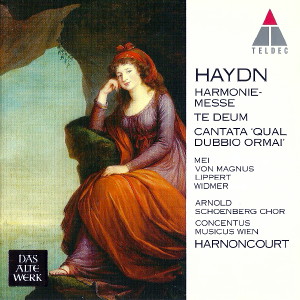

1 CD -

3984-21474-2 - (p) 1999

|

|

| Franz Joseph

Haydn (1732-1809) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Harmoniemesse in B flat

major, Hob. XXII:14 - for soloists

(SATB), four-part chorus and orchestra |

|

43' 09" |

|

| Kyrie |

7' 49" |

|

1

|

| Gloria |

10' 25" |

|

|

- Gloria in

excelsis Deo

|

2' 15" |

|

2

|

| - Gratias

agimus tibi |

4' 58" |

|

3

|

| - Quoniam

tu solus |

3' 12" |

|

4

|

| Credo |

11' 19" |

|

|

- Credo in

unum Deum

|

3' 07" |

|

5

|

- Et

incarnatus est

|

3' 18" |

|

6

|

- Et

resurrexit tertia die

|

4' 54" |

|

7

|

| Sanctus |

3' 09" |

|

8

|

| Benedictus |

4' 08" |

|

9

|

| Agnus

Dei |

6' 19" |

|

|

- Agnus Dei

|

3' 23" |

|

10

|

| - Dona

nobis oacem |

2' 56" |

|

11

|

|

|

|

|

| Cantata "Qual dubbio ormai",

Hob. XXIVa:4 - for soprano,

chorus and orchestra |

|

15' 00" |

|

- Recitativo

accompagnato - "Qual dubbio ormai"

|

1' 54" |

|

12

|

| - Aria

- "se ogni giorno Prence invitto" |

8' 50" |

|

13

|

| - Recitativo

- "Saggia il pensier" |

0' 20" |

|

14

|

| - Coro

- "Scenda propizio un raggio" |

3' 56" |

|

15

|

|

|

|

|

| Te Deum in C major, Hob.

XXIIIc:1 - for soloists (SATB), four-part

chorus and orchestra |

|

7' 34" |

|

- Te Deum

Laudamus

|

3' 07" |

|

16

|

- Te ergo

quaesumus

|

0' 47" |

|

17

|

- Aeterna

fac cum sanctus tuis

|

3' 40" |

|

18

|

|

|

|

|

| Eva Mei, Soprano |

|

Elisabeth von

Magnus, Contralto

|

|

| Herbert Lippert,

Tenor |

|

| Oliver Widmer,

Bass |

|

|

|

Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

Master

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (with original

instruments)

|

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violin |

-

Dorle Sommer, Viola |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violin |

- Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violin |

-

Dorothea Guschlbauer, Violoncello |

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer, Violin |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Violone |

|

| -

Editha Fetz, Violin |

-

Enno Senft, Violone |

|

| -

Thomas Fheodoroff, Violin |

-

Robert Wolf, Traverflöte |

|

| -

Annelie Gahl, Violin |

-

Hans Peter Westermann, Oboe |

|

| -

Silvia Iberer-Walch, Violin |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe |

|

| -

Barbara Klebel, Violin |

-

Gerald Pachinger, Clarinet |

|

| -

Annemarie Ortner, Violin |

-

Herbert Failtynek, Clarinet |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violin |

-

Eleanor Froelich, Fagott |

|

| -

Elisabeth Stifter, Violin |

- Christian Beuse, Fagott |

|

| -

Christian Tachezi, Violin |

-

Andreas Lackner, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Mary Utiger, Violin |

-

Herbert Walser, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Gertrud Weinmeister, Violin |

- Glen Borling, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Lynn Pascher, Viola |

-

Edward Deskur, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Gerold Klaus, Viola |

-

Dieter Seiler, Pauken |

|

| -

Ursula Kortschak, Viola |

- Herbert Tachezi, Orgel |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Pfarrkirche,

Stainz (Austria) - luglio 1998 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Martina Gottschau / Martin Sauer

/ Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

Classics "Das Alte Werk" - 3984-21474-2

- (1 cd) - 65' 56" - (p) 1999 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

On

Wednesday 8 Septemher 1802 the

seventy-year-old Joseph

Haydn conducted his last great work in

die Bergkirche at Eisenstadt: like

its five

predecessors, his Mass no 14

in B flat major

Hob XXII:14 was written

to celebrate the name-day

of the Princess Maria

Hermenegild Esterházy.

The magnificence of the occasion is

clear from a description left by the

Austrian diplomat Prince Ludwig Starhemberg,

who noted in his

diary how the guests waited upon the

princess, after which they all “drove

in a large procession

of several carriages to the Mass. -

Superb Mass, excellent new piece by

the celebrated Haydn [...]. Nothing

could have been more beautiful or more

finely executed; after

the Mass we returned to the palace.

[...] Later a great and splendid

banquet, as exquisite as it was

wellattended, music during the meal,

The prince drank the

princess's health, fanfares and

twentyone gun salutes in reply, -

then several other toasts, including

my own and that of Haydn, who was

dining with us. I myself

proposed it. After dinner, in

evening dress to the ball, which was

quite superb, like a court ball;

together with her daughter,

Princess Maria opened it with a menuet

à quatre; afterwards nothing but

waltzes."

As in London. where, between 1791 and

1795, he had frequented the highest

circles in society, so, too, in

Eisenstadt, Haydn sat at the same

table as aristocrats and diplomats and

was treated as their equal, an

accolade rnarking the

culmination of an association with the

Esterházy family

which, beginning with his appointment

as their vice-Kapellmeister

in 1761, had

lasted lor more than forty years.

Although Haydn had

suffered from poor health following

the exertions bound up with the

composition of his two oratorios, Die

Schöpfung

(1796-8)

and Die Jahreszeiten

(1799-1801), and described himself as

“an increasingly sickly old boy", his

final Mass continues to demonstrate

his ability to engage with the most

modern trends in

music. The work hecame

known as his Harmoniemesse on

the strength of its unusually large

complement of wind instruments (in

Austria, wind ensembles were known as

Harmoniemusik), but the name

could equally well be applied to its

forward-looking harmonic textures. Not

only in the dark-hued, unusually long

Kyrie, with the chorus's

literally terrifying fortissimo

entry on the chord of

a diminished seventh, but above all in

the "Cricifixus", Sanctus and Agnus

Dei, Haydn’s harmonic writing emerges

as his most irnportant

means of expression. He had grown up

in the late Baroque tradition -

a tradition typified by strict

counterpoint and the use of rhetorical

figures in the melodic

line - but by the end

of his career he was exploring

a musical language that already bears

within it many of

the hallmarks of early Romanticism.

Time and again the listener is

surprised by unexpected modulations,

especially to third-related

tonalities. And nowhere is this

surprise greater than in the transition

from the first part

of the Agnus Dei, which ends in D major,

to the B flat major fanfares

of the "Dona

nobis pacem", a tutti that erupts with

elemental suddenness and might almost

suggest the trumpets of the Last

Judgement. But for Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, who sees a

direct link between Haydn's "Dona

nobis pacem" and the corresponding

movement in Beethoven's Missa

solemnis, this etherwordly

element is less important than the

wholly secular contrast between "the

joy of peace and the despair of

conflict".

If Haydn took an interest

in eschatological matters in the

years around 1802, it was not only

because of his age. He was also

thinking of writing a third great

oratorio on the theme of the

Apocalypse, for which he wanted

Christoph Martin Wieland to

provide the libretto. In the

event, nothing came of their

proposed collaboration, and, with

the exception of the unfinished

String Quartet op. 103 and a

handful of English folksongs,

Haydn published no more works. He

made his final public

appearance on 26 December 1803,

conducting his own Seven

Last Words from the Cross,

after which he withdrew from

active music-making.

The Te Deum

no. 1 Hob. XXIIIc:1 and the

cantata Qual dubbio ormai

Hob. XXIVa:4 take us back to

Haydn's early years in the

service of the Esterházys,

when the young

vice-Kapellmeister was

contracted to write sacred and

secular occasional pieces for performance

at court celebrations. It is

not entirely clear for what

occasion Haydn wrote the present

Te Deum, although it may have

been heard for the first time

at an official reception for Prince

Paul Anton and his new wife,

Marie Therese Erdödy, at

Eisenstadt on 10 January 1763.

The work, which is

only 150 bars long,

falls into three sections in keeping

with the late Baroque Viennese tradition.

The opening section ("Te

Deum laudamus") begins

with a largely homophonic choral

passage accompanied by the sort of

violin figurations that are typical of

this period. Next comes

an extended

tenor solo ("Tu Rex

gloriae, Christe") that is iteself

divided into

two contrastive sections, the second

of which ("Te ergo

quaesumus") is a sustained appeal for

divine assistance that

explores minor-key

tonalities. With the third section

("Aeterna fac"), Haydn

whips up the tempo and returns to the

earlier mood of jubilation,

with the obligatory fugue on the words

"In te Domine speravi",

an emotionally charged

passage full of hope

that leads back to the music of the

work's beginning, thus

giving the whole a fine sense of

unity. Contemporary

copies of the score and parts in

several Austrian monastery libraries

attest to the work's

popularity in the 18th century. After

1800, however, it fell into

total neglect and was

not heard again until its revival

at the 1967 Holland

Festival.

Also in around 1763/4

Haydn wrote a set ol five

Italian cantatas for

one or more solo voices,

chorus and orchestra. Like

Johann Sebastian

Bach's secular cantatas and the "court

odes" of

Purcell and Handel,

they served to provide an official and

poetically charged record of important

events in the lite of the court -

events such as the prince's return from

abroad or his recovery from some

serious illness or other. The cantata

Qual dubbio ormai, which

received its first performance

at Eisenstadt on 6 December 1764,

celebrated not only Prince Nikolaus

Esterházy's name-day

but also his appointment as Captain of

the Noble Hungarian Bodyguard,

an appointment that was a mark of

particular honour.

It is clear from the

orchestral and solo writing that by

the date in question Haydn

had already gained some

experience in the field

of music theatre, although the

virtuoso writing for obbligato

harpsichord in the soprano aria, "Se

ogni giorno", that forms the cantata's

central section is certainly unusual.

But there is little doubt that Haydn

played this

part himself and that the

enjoyed

accompanying the soprano's breath-taking

fioriture. (In

the present recording,

the haipsichord part

is played on the organ.) Although this

piece was one of the

last examples of a Baroque convention

that died out in Austria with

Haydn’s Eiseintadt

cantatas, it is none

the less still capable of giving us a

fair impression of the

much-vaunted

splendour of the

Esterházy court.

Dorothea

Schröder

Translation:

Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|