|

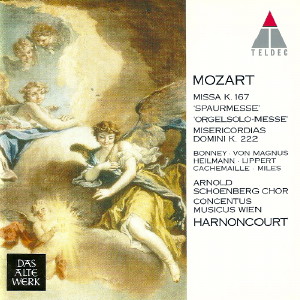

1 CD -

3984-23570-2 - (p) 1998

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Missa in honorem Ssmae

Trinitatis in C major, KV 167 |

|

30' 36" |

|

| - Kyrie |

3' 05" |

|

1

|

| - Gloria |

4' 18" |

|

2

|

| - Credo |

12' 59" |

|

3

|

| - Sanctus |

1' 10" |

|

4

|

| -

Benedictus |

3' 40" |

|

5

|

- Agnus Dei

|

5' 24" |

|

6

|

| Missa brevis in C major, KV

258 "Spaurmesse" |

|

16' 13" |

|

| - Kyrie |

1' 51" |

|

7

|

| - Gloria |

2' 38" |

|

8

|

| - Credo |

5' 00" |

|

9

|

- Sanctus

|

1' 04" |

|

10

|

| -

Benedictus |

2' 03" |

|

11

|

| - Agnus Dei |

3' 37" |

|

12

|

| Kyrie in G major, KV 89 (73k) |

|

4' 03" |

13

|

| Misericordias Domini in D

minor, KV 222 (205a) |

|

7' 33" |

14

|

| Missa brevis in C major, KV

259 "Orgelsolo-Messe" |

|

14' 32" |

|

| - Kyrie |

2' 10" |

|

15

|

| - Gloria |

2' 06" |

|

16

|

| - Credo |

3' 34" |

|

17

|

| - Sanctus |

1' 05" |

|

18

|

| -

Benedictus |

2' 23" |

|

19

|

| - Agnus Dei |

3' 14" |

|

20

|

|

|

|

|

| Barbara Bonney,

Soprano |

|

Elisabeth von

Magnus, Contralto

|

|

Herbert Lippert,

Tenor (KV 258)

|

|

| Uwe Heilmann,

Tenor (KV 259) |

|

Alastair Miles,

Bass (KV 258)

|

|

Gilles

Cachemaille, Bass (KV 259)

|

|

|

|

Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

Master

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (with original

instruments)

|

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violin |

-

Helmut Mitter, Viola (KV 222) |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violin |

- Peter

Schoberwalter, Viola (KV 222) |

|

-

Andrea Bischof, Violin (KV 222,

258, 259)

|

-

Gerold Klaus, Violin (KV 222) |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violin |

- Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello

(KV 222, 259) |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violin |

-

Max Engel, Violoncello (KV 222,

259) |

|

-

Silvia Walch-Iberer, Violin (KV

222, 258, 259)

|

-

Dorothea Guschlbauer, Violoncello

(KV 167, 258) |

|

-

Annemarie Ortner, Violin (KV

167, 222, 259)

|

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone (KV 222,

258, 259) |

|

-

Maighread McCrann, Violin (KV

222, 258, 259)

|

- Hermann Eisterer,

Violone (KV 167) |

|

-

Herlinde Schaller, Violin (KV

222, 259)

|

-

Hans Peter Westermann, Oboe (KV

167, 258) |

|

-

Maria Kubizek, Violin (KV 222,

259)

|

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe (KV 167. 258,

259) |

|

-

Editha Fetz, Violin (KV 167,

222, 259)

|

-

Omar Zoboli, Oboe (KV 259) |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter junior, Violin |

-

Milan Turkovič, Fagott (KV 258,

259) |

|

-

Christian Tachezi, Violin (KV

222, 258, 259)

|

-

Eleanor Froelich, Fagott (KV

167) |

|

-

Helmut Mitter, Violin (KV 167,

258, 259)

|

-

Firedemann Immer, Naturtrompete

(KV 258) |

|

-

Peter Schoberwalter, Violin (KV

167, 258, 259)

|

-

Ute Hartwich, Naturtrompete (KV

258) |

|

-

Walter Pfeiffer, Violin (KV 167,

258)

|

-

Andreas Lackner, Naturtrompete

(KV 167, 259) |

|

-

Mary Utiger, Violin (KV 258)

|

-

Herbert Walser, Naturtrompete

(KV 167) |

|

-

Christine Busch, Violin (KV 258)

|

-

Martin Rabl, Naturtrompete (KV

167) |

|

-

Daniel Sepec, Violin (KV 258)

|

-

Martin Patscheider, Naturtrompete

(KV 167) |

|

-

Thomas Fheodoroff, Violin (KV

258)

|

-

Dieter Seiler, Pauken (KV 258) |

|

-

Gerold Klaus, Violin (KV 259)

|

-

Michael Vladar, Pauken (KV 167,

259) |

|

-

Irene Troi, Violin (KV 167)

|

-

Dietmar Kühlböck, Posaune (KV

258) |

|

| -

Gertrud Weinmeister, Violin (KV

167) |

-

Josef Ritt, Posaune (KV 258,

259) |

|

-

Veronika Kröner, Violin (KV 167)

|

- Horst Kühlböck, Posaune

(KV 258, 259) |

|

-

Ursula Kortschak, Violin (KV

167)

|

- Yuji Fujimoto, Posaune

(KV 259) |

|

-

Barbara Klebel, Violin (KV 167)

|

-

Herbert Tachezi, Orgel |

|

-

Annelie Gahl, Violin (KV 167)

|

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Casino

Zögernitz, Vienna (Austria) - febbraio

1992 (KV 89), ottobre 1996 (KV 167)

Pfarrkirche, Stainz (Austria) - luglio

1990 (KV 222, 259), luglio 1994 (KV 258) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Renate Kupfer (KV 89, 259) /

Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 3984-23570-2 - (1 cd)

- 73' 09" - (p) 1998 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Mozart's

Church Music against a

Background of Changing Styles

The

majority of Mozart's Salzburg Masses

were written at a time of social and

aesthetic change - changes that also

affected sacred music and, above all,

the role of music in celebrating Mass.

In the years around the middle of the

18th century, settings of the missa

solemnis were notable for their

lavish instrumentation and for their

interplay between elaborate fugal

writing for the chorus and virtuoso,

aria-like passages for the vocal

soloists, their individual sections

often so distended that churchgoers

may well have thought that they were

attending a concert rather than a

service. But by the final third of the

18th century a countermovement had

come into existence, initially within

the church itself, that aimed to

introduce a simpler fornt of sacred

music and that finally received

support from the reforms of the

Emperor Joseph II. It was in the wake

of this development that a more

modest, shorter form of the Mass, the

missa brevis, came to

prominence. As Mozart told his

teacher, Giovanni Battista Martini, in

a critically worded letter of 4

September 1776, the Prince-Archbishop

of Salzburg, Hieronymus Colloredo, now

insisted that “a Mass, with the whole

Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Epistle sonata,

Offertory or motet, Sanctus and Agnus

Dei must last no longer than

three-quarters of an honr".

It is interesting to observe the way

in which the two leading composers of

the period dealt with these

rcstrictions: Joseph Haydn simply

stopped writing church music during

these years, returning to the medium

of the missa solemnis only

towards the end of his life with his

famous six late Masses, while Mozart,

by contrast, made the shorter missa

brevis very much his own,

turning it into a vehicle for his

highly personal religious views.

Mozart's Salzburg

Masses: an expression of personal

faith?

Mozart's

Salzburg Masses have often been

described as purely functional, but it

must be remembered that at this time

every piece music was intended to

serve some function or other. Although

he did not ignore existing conventions

altogether, Mozart was still able to

fill out the prescribed form of the

Mass with his own very personal ideas.

None of these settings could be

described as mere hackwork, but all

are the expression, rather; of a very

personal approach to religion. Several

contain a serenely cheerful,

even childishly naïve view of

paradise, while the many elements of

folk music and even dance that are

found here produce an impression of

gaiety that on occasion extends to

boisterous joviality.

Mozart developed his own specific

musical imagery for thw individual

sections of the Mass. In the Kyrie,

for example, he very often creates an

impression of majestic

unapproachability, while the Christe

tends, rather, to emphasise the human

element. And in the gestures of

entreaty at the words "eleison" and

"miserere" and also in the "Dona nobis

pacem", we often find writing that is

urgent and impatient and even angry in

its demands. In the "Qui tollis", the

sheer weight of the burden of sin can

he physically felt in the instrumental

accompaniment, and at the words

“judlcare vivos et mortuos", the Last

Judgement is generally depicted in a

way that implies great rigour but

occasionally also a certain childlike

naïveté. In the "Crucifixus" we

can sometimes hear the blows with

which the nails are driven into the

Cross, whereas the passages associated

with the words "Spiritus Sanctus" are

always rery light in tone, dancelike

and almost ethereal, like a bird on

the wing. The Sanctus expresses a

tremendous sense of awe and the

Benedictus, finally, occasionally

suggests the triumphant entry into

Jerusalem, while on other occasions

assuming the form of gentle music for

the Elevation, its paradisal lightness

of touch evoking the idea of Christ's

presence in the Eucharist.

Missa in honorem

Sanctissimae Trinitatis K. 167

The

Missa in honorem Sanctissimae

Trinitatis in C major K. 167

presumably received its first

performance on Trinity Sunday - 6 June

- 1773. Forrnally speaking, it

represents a hybrid form of the Mass,

combining elements of the missa

solemnis and missa brevis.

Its lavish orchestral resources,

including four trumpets (two of which

are scored for the clarino

register), timpani, two oboes, two

violins, bass and organ, together with

its extended instrumental preludes and

interludes, the concluding fugues in

the Gloria and Credo and the fugal

"Dona nobis pacem" all reflect thc

tradition of the missa solemnis,

yet Mozart also sought to meet the

then current demands of the missa

brevis type of Mass with the

succinctness of his setting and the

relative lack of textual repeats.

Particularly striking is his decision

to dispense with any vocal soloists:

the work is scored throughout for

chorus and orchestra, with the highly

contrastive and emotionally charged

instrumental writing often claiming

attention over the generally

homophonic choral textures. Especially

effective is the contrast between the

mysterious-sounding a cappella

passages in the "Et incarnatus” and

the abrupt transition to the

"Crucifixus", which is shot through

with interjections on the strings

suggesting voices raised in outcry and

illustrating the drama of events as

they unfold on Golgotha.

Missa brevis K.

258 ("Spaur Mass")

K 258 is

a typical missa brevis, albeit

one of a festive nature, its character

determined, above all, by its lavish

orchestration, with two trumpets,

timpani, three colla parte

trombones and two oboes (the parts for

which were discovered only later), in

addition to the usual strings, bass

and organ. It is unclear whether the

work was written to mark the

ordination of the Salzburg canon,

Count Ignaz Joseph Spaur, as assistant

bishop of Brixen, since this

last-named ceremony took place in

November 1776, whereas the work itself

is dated December. The independent

orchestral writing, often drawing on

motifs from folk music and dance, is

contrasted with the spare but

emotionally charged writing for chorus

and soloists. With its interplay

between majestic choral passages and

more lyrical solo episodes, the

lively, triple-time Kyrie is

reminiscent in character of a rondeau.

There are very few textual repeats in

the Gloria and Credo, where the

contrast between the lyrical tenor

solo of the "Et incarnatus" and the

darkly threatening choral cries in the

"Crucifixus", underscored by the

oppressive sonorities of the three

trombones, is particularly affecting.

The very brief Sanctus is followed by

an animated, dancelike Benedictus, its

interplay between solo quartet and

choral outbursts illustrating the idea

of a festive procession. A serenely

lyrical Agnus Dei brings the work to

an end.

Missa brevis K.

259 ("Organ Solo Mass")

Like K.

258, K. 259 is also believed to date

from the end

of 1776 and may have been written

for the Feast of the

Innocents, 28 December, which

was also

the day reserved for the members of

the boys’ choir who sang the

soprano and alto parts in the

Salzburg Cathedral choir. The work

fully reflects Colloredo's demand for

brevity, a demand ironically

encapsulated in Mozart's comment that

"a special study is required for this

type of composition". Two trumpets,

timpani and (in some of the copies of

the parts) oboes lend this missa

brevis its festive stamp. It

takes its name from the concertante

role of the organ in the Benedictus.

The Kyrie is almost folklike in its

ebullient mood, while the extreme

brevity of the Gloria is further

underlined by the rapid interchange

between solo and choral sections. At

the heart of the ternary Credo is the

liltingly lyrical “Et incarnatus" for

solo quartet followed by the

emotionally intense "Crucifixus" for

choir. Mozart wrote two versions of

the Sanctus, later deciding in favour

of the second one. A particular high

point is the Agnus Dei, which

anticipates the cantilena of the

Countess's aria, "Porgi, amor", from

Act Two of Le nozze di Figaro.

Overall, K. 259 contains clear

structural parallels with the Missa

brevis K. 247. But perhaps the

particular charm of this setting lies

in its natural simplicity, a

simplicity that exudes a cheerful and

folklike piety.

The present recording is supplemented

by two brief sacred pieces. Cast in

the form of a canon for five soprano

voices, the Kyrie in G major K. 89

(73k) was probably written in 1772 in

the context of Mozart’s lessons in

counterpoint with the famous Bolognese

pedagogue, Giovanni Battista Martini,

who was one of the leading teachers of

imitative counterpoint, an art that

formed an essential part of the sacred

music tradition of the 17th and 18th

centuries.

The Offertory, Misericordias

Domini, in D minor K. 222 was

written in Munich in early 1775, when

Mozart was in the city for the first

performance of his opera La finta

giardiniera on 13 January. With

its elaborate contrapuntal writing,

this piece provides yet further proof

of Mozart's mastery in this particular

form. In writing it, he was picking up

an older Salzburg tradition and partly

reworking material from a piece by

Johann Ernst Eberlin.

Johanna Fürstauer

Translation:

Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|