|

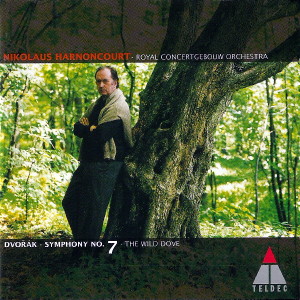

1 CD -

3984-21278-2 - (p) 1998

|

|

| AntonŪn

DvořŠk (1841-1904) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 7 in D minor,

Op. 70 |

|

38' 49" |

|

| - Allegro maestoso |

11' 52" |

|

1

|

| - Poco adagio |

9' 37" |

|

2

|

| - Scherzo: Vivace |

7' 55" |

|

3

|

- Finale: Allegro

|

9' 25" |

|

4

|

| The Wild Dove, Op. 110 |

|

19' 46" |

|

| - Andante, marcia funebre /

Allegro - lento / Molto vivace / Andate

/ Lento, tempo di marcia |

19' 46" |

|

5

|

|

|

|

|

| Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Het

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam (Olanda) -

marzo 1998 (Op. 70), dicembre 1997 (Op.

110) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

live /

studio (Op. 110)

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut MŁhle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 3984-21278-2 - (1 cd) - 58' 46" - (p)

1998 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

"This music

gets under my skin"

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt in conversation with Monika

Mertl - On DvořŠk and the nature of

Czech music

Monika Mertl: The present recording

marks the beginning of a period of

intense involvement with Czech music for

you. It is a new departure for you as a

conductor, though it also finds you

returning to something already familiar

to you.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt: For me, the music

of Bohemia and Czechoslovakia is quite

simply Austrian music, and I feel a

great familiarity with it, perhaps also

through my family, which has Czech

roots. You could also say that it's a

return, since I played a lot of this

music during my time as a cellist with

the Vienna Symphony Orchestra - and

played it, moreoveh with immense

enjoyment.

The DvořŠk Cello Concerto was one of

your showpieces during your youth.

Yes, I played it for Karajan when I

auditioned for a place in the Vienna

Symphony Orchestra.

You've approached DvořŠk via

Schumann and Mendelssohn.

Yes, in that respect I've followed

DvořŠk's own development. His early

works were strongly influenced by

Mendelssohn and Schumann. The composer

whom we really think of as DvořŠk

emerged only with his Sixth Symphony.

It`s interesting that for a long time

the early symphonies weren't numbered at

all. The first five were ignored.

There's no doubt that this is also due

to the fact that DvořŠk himself felt

that it was only later that he

discovered his true voice as a composer.

He suffered from too many ideas and

first had to impose some sense of

order an them, you mean?

There's no other composer of his

generation who was so full of ideas. His

contemporaries envied him immensely. But

after a while he learnt to control this

flood of inspiration - to overwhelming

effect. He himself says in the context

of this symphony: "In creative brains

there is an impulse to write that is

very hard to curb."

He substantially cut the second

movement following the first

performance in London in l885.

Yes, forty bars were cut. He wrote to

his publisher, Fritz Simrock: "The

Adagio is now much shorter and more

compact, and I'm now certain that

there's not a single note too many."

It's all bound up with this exuberance

of invention. A second stage in the

operation was necessary to find the

right sense of balance.

How important is the national aspect

of this music?

It's something that moves me deeply.

During my time as an orchestral

musician, a very large percentage of the

players were either Czech themselves or

had Czech ancestors. Half the orchestra

would burst into tears whenever we

played a symphony by DvořŠk. I myself

feel something of this emotion - I won't

call it sentimentality. This music gets

under my skin. There's no doubt that

itís the Slav element, the sense of

valediction, this vast tear. This

element is highlighted in a way you

don't find anywhere else in Central

European music. At the start of the

Scherzo I always go weak at the knees.

You're aware of the sense of national

identity in this music. DvořŠk felt that

it was important for this wealth of

musical talent to play a role in art

music, too. For nearly 200 years, almost

all the horn players in Europe were

Czech! Wonderful music was written, and

with Smetana and, above all, DvořŠk it

was suddenly music of international

stature, not just a local affair.

This was the period of Czech

nationalism. DvořŠk had played the

viola in the Provisional Theatre

Orchestra in Prague for almost ten

years.

He must have been a very good viola

player. Itís said that his solo in

Aennchen's aria in Der FreischŁtz

["Einst tršumte meiner sel'gen Base"]

was a high point in performances of the

opera. He comes from inside, so to

speak, from inside the orchestra. You

can tell from the viola part and from

the way in which he doesn't use the

instrument for long periods but then

brings it in again at a very specific

and generally very important point.

But what is important in DvořŠk's

music is that it isn't folk music,

although folk music was the starting

point for his inspiration.

He didn't need to use folk music. Even

his Slavonic Dances are his own

invention. He copied the rhythms of folk

music, but not the music itself.

You're starting with the Seventh,

which is not all that popular. In

other words, there's no problem with

the performing tradition of this

piece.

I've far more memories of the Eighth and

the Ninth, whereas I played the Seventh

only rarely. I have the feeling that I'm

able to go straight to the heart of this

music and donít have to sidestep a whole

pile of traditions that are inauthentic

precisely because they're of recent

date.

Why do you think the Seventh

Symphony is so rarely played?

There are symphonies that conductors

avoid because they need lots of

rehearsals and a good deal of

preparatory work before you can

understand them and make sense of them.

Beethoven's Fourth is one such piece, as

is Schubertís Fourth. It`s thought that

they're less likely to be successful in

performance - not that I believe such

remarks for a moment.

The Seventh is in fact seen as

DvořŠk's symphonic masterpiece.

Yes, but only now. Eduard Hanslick

thought that there was too much trombone

writing in it and told Simrock: "The

Scherzo would be delightful, but in the

other movements the trombones devour too

many of the contours." He was

particularly critical of the

instrumentation, a criticism that

annoyed DvořŠk. Later that same month

DvořŠk wrote to Simrock to say that he

had received an invitation to conduct

the D minor Symphony in Frankfurt: ďIf I

see you there, I should like to show you

that the contours are unmistakable, even

with the trombones. It depends entirely

on how you do it." DvořŠk was convinced

that he had written it correctly - and I

may add that I feel the same.

Also, this was the very time that

Bruckner was having problems with the

various orchestral registers. With

Brucknen however, the orchestral sound

is built up much more on the trombones,

whereas in DvořŠk's case the trombones

are used in particular passages only to

reinforce the sound, they never form the

actual basis of the instrumentation. If

they're played too loudly, the piece at

once becomes overblown and loses its

lightly-sprung character

Brahms and Hanslick were forever

criticising DvořŠk.

Brahms was very circumspect in his

criticisms, since he also envied DvořŠk.

And DvořŠk was so much in awe of Brahms

that he asked him to read the proofs of

his scores. It's a very interesting

relationship. They were so different in

their basic attitude to art, yet were

able to respect each otherís results.

And there was nothing really to

criticise. In this way it was possible

for them to be friends, a friendship

sustained by great admiration; it is

rare for two such great composers of the

same generation to be on such good terms

with one another. Itís as though Handel

and Bach had been friends.

To a certain extent they were

complementary figures.

With DvořŠk, youíre much more directly

involved in the action, what he has to

say is very spontaneous. With Brahms, it

is the artistry that predominates, you

have the feeling that youíre not looking

at it directly but through some kind of

optical instrument. I certainly don`t

want to sound dismissive, itís just that

one is conscious of the art that has

gone into it.

The most familiar part of the

Seventh Symphony is its Scherzo, which

sounds rather different in your own

interpretation.

What is important are the phrase

markings that obscure the rhythm at the

beginning. Only later is this rhythm

strongly accented. Initially, the

listener doesn't know whether this

jig-like dance is the Scherzo or whether

it is what the cellos and bassoon are

playing in unison. Itís really only a

variation of the other theme, but it

sounds like the melody. Both are heard

together. And the rhythm here is very

soft-contoured - that`s definitely how

the composer wants it. Itís merely

hinted at. I find it incredibly moving,

because it makes the movement appear

positively to blossom. If you interpret

it simply as a way of bowing, rather

than as an articulation marking, the

result is something quite different.

DvořŠk is one of those composers who

was held in the highest regard even

during his lifetime, an esteem that

finds expression not least in the fact

that JonŠček and Mahler were the first

conductors to perform The Wild Dove,

for example.

JanŠček felt that DvořŠk's symphonic

poems were worth analysing, an analysis

that I've examined in detail myself.

DvořŠk, too, left notes on these pieces.

Then there are the poems by Karel Erben

- and then there's the music.

It`s clear that DvořŠk didnít think it

important to let his listeners know

exactly what is happening in the piece

and where. On the other hand, he was

very keen for them to know the contents.

Generally he made sure that audiences

were given a summary of those contents.

It`s not possible to say, however,

exactly how the poem is turned into

music. Sometimes the metrical patterns

of a particular strophe fit precisely

beneath the corresponding notes, but

then again there are passages that

DvořŠk himself ascribes to quite

different sections of the work, and

JanŠček's analyses, in turn, propose

completely different interpretations.

There are strophes that DvořŠk is said

to have omitted, but I can see very

clearly that he has done no such thing.

I think that this touches on a basic

principle of programme music. It was

incredibly important for DvořŠk that

these symphonic poems should have a

musical logic of their own, quite

independent of their programme, and that

they should be great music. That is the

decisive point. Works in which the music

merely illustrates a programme with

greater or lesser brilliancy I would

describe as programme music in the

pejorative sense of the term.

In this context it's impossible not

to think of Richard Strauss. Also

sprach Zarathustra was written in the

same year as The Wild Dove - 1896.

And he'd already written some very big

works like Don Juan, Tod und Verklšrung

and Till Eulenspiegel. In my own view,

the mother of all symphonic poems is

Mendelssohn's Die schŲne Melusine, which

in turn is descended from Haydnís

symphonies and Beethoven's piano sonatas

and symphonies. No one ever doubted that

a Haydn symphony was derived from some

extra-musical statement: in Haydn's day

this was regarded as completely

self-evident. The only question was

whether one should tell the audience or

whether it was enough that it was there.

The musical character of such a story

soon becomes clear: You can often hear

that a work based on contrast and

reaction loses its expressive force and

meaning when reduced to the level of a

series of paratactical ideas.

DvořŠk intended ta write these

ballads much sooner and clearly

planned a longer series.

There's no doubt that these poems meant

a lot to him. At a time when something

like a sense of patriotism was emerging,

the world of legends associated with a

particular nation inevitably became

especially important. Erben wrote poems

based on the old Czech folk tales and

legends, all of them gruesome stories,

like all the worlds fairy tales. They

deal with questions of guilt and fate

and with ways of dealing with guilt and

fate, morally and legally.

The piece is extremely complex,

monothematic, with everything derived

from the opening funeral march, and at

the end we hear a variation on the

opening march theme.

It's a reminiscence of the motif of

grief and Iamentaticn from the

beginning: first it's the death of the

husband, then the death of the widow

herself. The guilt theme keeps on

returning, too. The themes associated

with grief and guilt are derived from

each other and are so intricately

interwoven that itís difficult to say

where grief ends and pain begins. This

use of derivation technique produces

such a unity that there's no real need

for any textual support: everyone can

hear where the dove is involved. The

wild dove is the voice of the conscience

of this widow, who killed her husband.

It's like tinnitus ringing in your ear,

something you can't bear but from which

you can't escape.

DvořŠk's ending is different from

that of the poem.

In strophes 25 and 26, it effectively

says "No grave, only heavy stones. The

curse on her name weighs even more

heavily." JanŠček writes: "Beneath the

weight of the chords, which almost

stifle one another, we virtually feel

the burden that presses down on the

wretched woman's body like an enormous

stone." The harmonies are genuinely

terrifying, but then the music modulates

quite unconcernedly from F minor to C

major. DvořŠk redeems the widow by

musical means.

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|