|

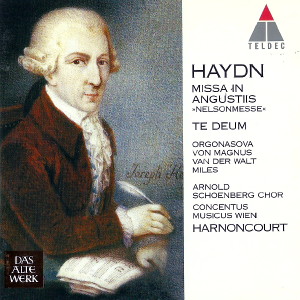

1 CD -

0630-17129-2 - (p) 1998

|

|

| Franz Joseph

Haydn (1732-1809) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Missa in angustiis

"Nelsonmesse" in D minor, Hob. XXII:11 |

|

41' 31" |

|

| - Kyrie |

5' 07" |

|

1

|

| - Gloria |

12' 00" |

|

2

|

| - Credo |

10' 29" |

|

3

|

| - Sanctus |

2' 21" |

|

4

|

| -

Benedictus |

5' 49" |

|

5

|

- Agnus Dei

|

5' 45" |

|

6

|

| Te Deum in C major, Hob.

XXIIIc:2 |

|

9' 35" |

7

|

|

|

|

|

| Luba Orgonasova,

Soprano |

|

Elisabeth von

Magnus, Contralto

|

|

| Deon van der Walt,

Tenor |

|

| Alastair Miles,

Baritone |

|

|

|

Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

Master

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (with original

instruments)

|

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violin |

-

Penny Howard, Violoncello |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violin |

- Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violin |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Violone |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violin |

-

Robert Wolf, Traverflöte |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violin |

- Hans Peter

Westermann, Oboe |

|

| -

Thomas Fheodoroff, Violin |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe |

|

| -

Silvia Iberer-Walch, Violin |

-

Gerald Pachinger, Clarinet |

|

| -

Barbara Klebel, Violin |

- Andrea Wiser, Clarinet |

|

-

Veronika Kröner, Violin

|

-

Eleanor Froelich, Fagott |

|

| -

Annemarie Ortner, Violin |

-

Michael McGraw, Fagott (Te Deum) |

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer, Violin |

- Eric Kushner, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violin |

-

Alois Schlor, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Christian Tachezi, Violin |

-

Andreas Lackner, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Irene Troi, Violin |

-

Herbert Walser, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Mary Utiger, Violin |

-

Christian Gruber, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Gertrud Weinmeister, Violin |

- Dietmar Küblböck,

Posaune |

|

| -

Lynn Pascher, Viola |

-

Othmar Gaiswinkler, Posaune |

|

| -

Gerold Klaus, Viola |

-

Gerhard Proschinger, Posaune |

|

| -

Ursula Kortschak, Viola |

-

Martin Kerschbaum, Pauken |

|

| -

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Orgel |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Casino

Zögernitz, Vienna (Austria) - giugno 1996 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 0630-17129-2 - (1 cd)

- 51' 19" - (p) 1998 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Haydn was in London

for his second extended visit to

England when he learnt of the death of

his employer, Prince Paul Anton

Esterházy, in January 1794. Paul

Anton's successor was Nikolaus II, who

now summoned Haydn back to Austria as

part of his plan to reorganise the

Esterházy orchestra disbanded by his

father. The new prince`s musical

interests were directed, in the main,

at sacred music, with the result that

from now on Haydn`s chief task was to

write an annual Mass for the name day

(8 September) of the Princess Marie

Hermenegild. Between 1796 and 1802 he

duly obliged with six of the most

impressive Masses in the whole history

of liturgical music. Each Mass,

moreover, han its own individual

character, while together they form a

unique complex of pieces: together

with the oratorios The Creation

and The Seasons on which the

now sexagenarian Haydn was also

working at this time, they constitute

a synthesis of the older concertante

principle (here transferred to the

interplay between soloists and chorus)

and the art of the late Baroque fugue,

thereby creating a new and

forward-looking style of church music

grounded in a modern handling of the

symphony orchestra.

The ‘Nelson Masss” Hob XXII:11 was the

third of the six Masses to be written

and follows the Heiligmesse

and the Paukenmesse. Composed

between 10 July and 31 August 1798, it

was originally described by Haydn as a

Missa in angustiis (Mass in

Time of Straitened Circumstances), the

title and perhaps also the darkly

threatening opening of the Kyrie in D

minor suggesting Austria’s fear that

Napoleon might emerge victorious from

the War of the First Coalition, which

had started in 1792. But, in spite of

the reference to a "time of straitened

circumstances", it would be wrong to

regard this as programme music, not

least because the work was written as

a festive Mass for a day of annual

celebration in the Esterházy

household. It received its first

performance in St Martin's parish

church in Eisenstadt on 23 September

1798, although on this occasion it was

given without the woodwind parts,

Nikolaus II having dismissed the

players on the grounds of economy.

Haydn made good the deficiency with a

complex part for the organ, which at

many points is used as a solo

instrument. When the Mass was

published by Breitkopf & Härtel in

1802, Haydn gave permission for the

Leipzig firm to reintroduce the

missing woodwind parts by

instrumenting the organ part.

Haydn was already rehearsing his new

Mass when, around 15 September 1798,

news of the coalition's victory in the

Mediterranean reached Eisenstadt,

turning the mood of gloom and

despondency into one of outright

celebration: on 1 August, Admiral Lord

Nelson, the commander of the English

fleet, had finally caught up with the

French fleet in Aboukir Bay between

Alexandria and Rosetta and, in a risky

manoeuvre, sailed into the bay and

captured or destroyed all but two of

the enemy vessels. It is said that

when Haydn heard of Nelson's exploit,

he added the martial trumpet fanfares

at the end of the Benedictus in an

expression of his delight and

admiration for the English maritime

hero, elevating the victorious admiral

to the status of a God-sent saviour.

This attempt to offer a post hoc

explanation of the work's more

familiar title may safely be consigned

to the dustbin of musical legend, for

trumpets and timpani were

traditionally and frequently used at

this point in the Mass. Just as in the

courtly life of the time they

signalled the arrival of a prince, so

they served here as a symbolic way of

greeting the Messiah “who cometh in

the name of the Lord".

Neither in the score of the Missa

in angustiis nor in its genesis

is the English naval hero’s memory

enshrined. Only its performing history

provides such a link: in September

1800, the Mass was performed in honour

of Lord Nelson when the latter spent

four days in Eisenstadt in the course

of a triumphal tour of Austria and

Prince Nikolaus II entertained his

famous guest, together with the

Emperor Franz II, with magnificent

banquets, firework displays, hunts and

balls. While the emperor and admiral

discussed their future tactics in

their war against Napoleon, Haydn

spent what time was left, when he was

not conducting concerts, in the

company of Lady Hamilton, Lord

Nelson's companion, a woman who,

beneath him in social rank, had to

bear her contemporaries' contempt.

Like many English women, she had

idolised Haydn since the tune of his

visits to London and now had the

pleasure of inviting him to accompany

her on the fortepiano (she had an

attractive soprano voice), thanking

him effusively when he presented her

with the autograph score of a short

cantata, Lines from the Battle of

the Nile, that he had written

especially for her: Nelson asked for

Haydn's old pen holder as a souvenir

and gave the composer a pocket watch

in return.

Among the works performed during this

visit is believed to have been the Te

Deum in C major Hob. XXIIIc:2,

which Haydn had written for the

Empress Marie Therese. Like Nikolaus

II Esterházy, the young wife of Franz

II did much to encourage "serious"

church music and commissioned pieces

from composers such as Haydn and

Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, whose

liturgically based works, unaffected

by the widely deplored and

trivialising influence of opera

buffa, could serve as models of

their kind. In Haydn's relatively

short but richly scored and

impressively unified Te Deum,

the double fugue "In te Domine

speravi" affords especially striking

proof of its composer's sovereign

command of traditional contrapuntal

practices. Conversely, the C major

carpet of sound at the end is a novel

stylistic feature that was to inspire

composers of later generations,

including Anton Bruckner. The Empress

Marie Therese and her family

presumably heard the The Deum

for the first time on the occasion of

their visit to Eisenstadt in 1800.

Soon after that the work fell into

oblivion until it was revived by the

BBC in 1958. As became abundantly

clear on that occasion, the C major Te

Deum is fully worthy of taking

its place alongside Haydn's six late

Masses as one of the elderly

composer's most magnificent works.

Dorothea

Schröder

Translation:

Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|