|

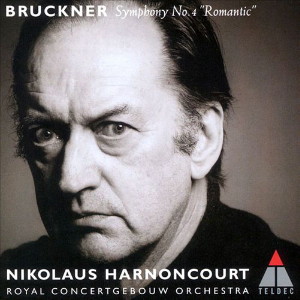

1 CD -

0630-17126-2 - (p) 1998

|

|

| Anton

Bruckner (1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony No. 4 in E flat

major "Romantic"

|

|

63' 07" |

|

| 1878/80 version |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - I. Bewegt, nicht zu schnell |

17' 46" |

|

1

|

- II. Andante quasi allegretto

|

14' 36" |

|

2

|

| - III. Scherzo: Bewegt |

10' 32" |

|

3

|

| - IV. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht

zu schnell |

20' 13" |

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

| Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Het

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam (Olanda) -

aprile 1997 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

live

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut MŁhle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 0630-17126-2 - (1 cd) - 63' 07" - (p)

1998 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

A Sinner in the Name of

Art

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt on Anton

Bruckner

"I

couldn't avoid Bruckner," Nikolaus

Harnoncourt admits. To a

musician schooled in the figures

of Baroque rhetoric and

small-scale form, Bruckner's

massive symphonies long

resisted all attempts on his

part to engage with them on

an active level. Only in the

wake of his interest in

Brahms's symphonies did

Bruckner - that "fantastic

composer" - take root in his

awareness, as though of his

own accord, "like some huge

weed". Following his

recording of the Third

Symphony, which critics

hailed as the dawn of a new

era in Bruckner

interpretation, Harnoncourt

has now recorded the Fourth,

again with the Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra, an

orchestra that can point to

a particularly tenacious

Brucknerian tradition but

which remains sufficiently

inquisitive and flexible to

accommodate Harnoncourt's

fresh approach.

Harnoncourtís picture of

Bruckner rests on deeper

insights into the composers

enigmatic personality.

"People always think of him

as God's organist sitting in

church and playing the

organ. And thatís how he

handles the orchestra.

That's how weíve all learnt

to see him. And then you get

these remarkable scherzo

elements, even in his outer

movements, and then it turns

out that, as a young man, he

was a keen dance musician -

what the Austrians call a 'Bratlgeiger',

in other words, someone who

plays the violin in taverns.

He must have been a good

violinist. This helps me a

lot in performing his works.

His music has a great deal

of physicality to it, in the

sense of rhythmic movement."

Bruckner's creative

confrontation with Wagner

is important not only for

his Third Symphony, with its

explicit dedication, but

also for his Fourth, the

"Romantic". "What

sparked this symphony was

the experience of Lohengrin.

For Bruckner, this was the

epitome of Romanticism in

music. It

must have been an incredible

experience for him,

musically. Yet, God-fearing

dogmatist that he was, he

was really the typical

anti-Wagnerian. The way in

which he fell under the

spell of Wagner's music

reminds me of Tšnnhauser

succumbing to Venus. To be

carried away by Wagner in

this way was tantamount to a

sin for Bruckner. I have the

impression that he thought

he then had to go and

confess his sins."

From this

point of view, the second

movement of the Fourth

Symphony, which Bruckner

himself described as a

"pilgrims' nocturnal

march", can certainly be

interpreted as a form of

penitential pilgrimage: ďIt

speaks of infinite

sadness. I can well

imagine that repentance

plays a major role here."

In daily life, Bruckner

was a simple-minded petit

bourgeois and grovelling

opportunist, in his art a

bold innovator who

transcended traditional

bounds as though it was

the most natural thing in

the world, a composer who,

in Harnoncourtís words,

was like a meteor in the

history of music, a

strange piece of lunar

rock on the road from

Schubert to Berg.

It

is, above all, this

irreconcilable conflict

within Bruckner's

personality and the

resultant hidden depths

that Harnoncourt wants to

bring out in his

interpretation. "I'm

always being asked how

religious one has to be to

play Bruckner`s

music. I don't think it

matters. He was a very

religious man, but in his

art he must have felt like

someone who was always

doing what was forbidden.

That suggests that he was

not bound by dogma.

Although he would write

down how many rosaries he

said each day, the sins he

committed in his music are

so black when judged by

the standards of his

religious faith that,

strictly speaking. he

would always have to be

praying for forgiveness."

This sense of inner

discord also characterises

Brucknerís approach to his

own works: "His obsequious

tendency to let his

interpreters have their

own way is well known, of

course. Whenever anyone

wanted to perform any of

his symphonies, he agreed

to all their suggestions

for changing it. A

symphony had barely to be

criticised for him to set

about reworking it. But

what was to be handed down

to posterity he kept

locked away in his

library. He was completely

unwavering in terms of

what, as an artist, he

felt to be uniquely and

ultimately correct. I

think it's

fairly easy to see what

prompted these revisions

and whether they are of

artistic merit or merely

of practical value."

Bruclner spent no fewer

than fifteen years, from

1874 to 1889,

working on his Fourth

Symphony, in some cases

making such farreaching

changes that the result is

another, far more advanced

piece. Harnoncourt, who

recalls some bizarre

adaptations from his days

as an orchestral musician,

considers the second

version of 1878-80,

on which the present

recording is based, to be

utterly convincing, even

though he is also

interested in the first

version.

"I can`t say that I

prefer one version to the

other. Each is of great

merit, so that you canít

play off one of them

against the other. As a

rule, the first version is

the most progressive and

almost always the most difficult

to digest and play -

technically and

rhythmically, above all

for the violins. So I also

have to take account of

the rehearsal situation."

Harnoncourt long ago

revised his earlier view

that Bruckner's

music had nothing to say

in terms of musical

discourse: "Thereís

a lot of dialogue in this

music. Itís

surprising to what extent

it is permeated with

questions and with answers

that are always sceptical,

never unambiguous.

Questioning figures,

figures of affirmation,

gestures of entreaty -

this is a musical

vocabulary that has grown

up over the centuries and

that every great composer

has at his disposal.

Gestures of consolation

are very often found in

Bruckner,

and they are also

extremely necessary, since

time and again he creates

the most terrible scandals

that would otherwise be

intolerable. And his vast

blocks of sound are, of

course, also meant to be

dialectical."

Even the "slowness"

of Brucknerís music that

is often quoted in this

context acquires a new

dimension in this

interpretation. For

Harnoncourt, it is

synonymous with

"spaciousness: a lot of

things need time to

develop. I

donít find Bruckner's

music slow, only that it

is sometimes played too

slowly."

The tempo markings, with

their constant

modifications and

ambiguous references to

earlier points in the

score are bound to be a

puzzle to every

conscientious performer

(and may perhaps be

analysed as examples of

schizophrenia).

Harnoncourt has examined

this question in detail

and sees these tempi as

part of a system that has

allowed him to uncover a

whole host of

microstructures: "I can

see that it's

organised along highly

sophisticated lines. And

these microstructures

acquire a specific meaning

when they are repeated at

the relevant point and

thereby produce a sense of

architectural form."

In

this way, Harnoncourt has

come to a clearer

understanding of

Bruckner's compositional

method: "I

think that, for him, it

was the second stage in

composing. First there was

the basic idea, which was

then put in order. Then

the periodisation of the

figures was precisely

fixed, a bar omitted or

another added. The result

is a very clear sense of

order and periodicity."

A particularly tricky

question in performing

Bruckner's

music has been

convincingly solved by

Harnoncourt with the help of

the Concertgebouw players:

"The brass here is really a

big problem. The woodwind

choir - flute, oboe,

clarinet, bassoon - is

supposed to be able to hold

its own in the face of the

battery of three trumpets,

four horns, three trombones

and tuba. With modern

instruments this is

completely impossible."

When performing the Third

Symphony, the Concertgebouw

horns had already agreed to

forgo the use of modern

instruments and to use the

simple horns that Bruckner

himself had in his minds ear

when writing this work. To

these were added trumpets

with rotary valves and

trornbones with the

narrowest possible bore,

thereby ensuring that even

in the loudest passages the

dominant impression was

still one of transparency

and tonal beauty.

The sense of power inherent

in this music is not

impaired by this. Into

his copy of the score

Nikolaus Harnoncourt has

transcribed a remark of Bruckner`s,

copying it out in large

letters: ďBecause the

present situation in the

world is weaker from a

spiritual point of view, I

take refuge in strength and

write powerful music."

Monika

Mertl

Translation: Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|