|

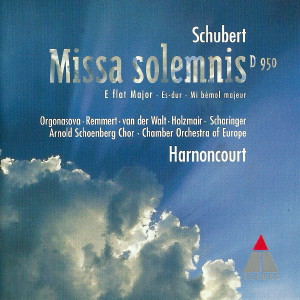

1 CD -

0630-13163-2 - (p) 1997

|

|

Franz

Schubert (1797-1828)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Missa No. 6 in E Flat major,

D 950 |

|

52' 29" |

|

| - Kyrie |

5' 26" |

|

1

|

| - Gloria |

12' 45" |

|

2

|

| - Credo |

15' 25" |

|

3

|

- Sanctus

|

3' 14" |

|

4

|

| - Benedictus |

5' 50" |

|

5

|

| - Agnus Dei |

9' 00" |

|

6

|

|

|

|

|

| Luba

Orgonasova, Soprano |

|

| Birgit

Remmert, Contralto |

|

| Deon

van der Walt, Tenor |

|

| Wolfgang

Holzmair, Baritone (Tenor

II + Benedictus) |

|

| Anton

Scharinger, Bass |

|

|

|

| Arnold Schoenberg Chor /

Erwin Ortner, Chorus Master |

|

| Chamber Orchestra

of Europe |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Stefaniensaal, Graz (Austria)

- 24 giugno 1995 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Wolfgang Mohr / Helmut Mühle /

Michael Brammann |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec - 0630-13163-2 -

(1 cd) - 52' 29" - (p) 1997 - DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Mass in E flat

major D 950

|

Schubert's

sixth and final setting of the Latin

mass dates from 1828, the final year

of his life. Like the A flat major

Mass of 1819-22, it was not written in

response to any commission, nor was it

the result of any external prompting.

For the conductor Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, this is only one of many

indications that, in composing it,

Schubert was responding to a quite

specific need to express his innermost

self: “This music ts not an act of

pious devotion lint Schnbert's

impassioned attempt to come to terms

with death." For Harnoncourt, these

last two Masses, which he conducted

for the first time on successive

evenings within the framework of the

tenth Styriarte, rank alongside

Beethoven's Missa solemnis as

the "greatest, most important and

artistically significant attempts to

come to terms with the Christian

liturgy. I believe that the social

situation and audiences' mental

outlook, together with the whole war

in which religion and life are bound

up with each other in Central Europe,

means that, for listeners and

musicians alike, these works have an

expressive force that is quite

literally capable of stirring us to

the very depths of our souls. I do not

think that a church is the right place

for us to attempt to confront their

underlying meaning," In consequence,

Harnoncourt chose to conduct these

works in the Stephaniensaal at Graz:

"I have heard masses performed in the

most varied venues and noticed how the

space itself is invariably transformd

by the piece's spiritual essence."

The home key of D 950 is E flat major,

a tonality which, according to the

German poet and writer on music,

Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart

(1739-1791), is "the tone of love,

devotion and intimate communion with

God, in three flat signs signifying

the Holy Trinity". If this choice of

tonality suggests that Schubert was

wanting to point up a contrast with

the "sepulchral" A flat major of the

earlier Mass and to strike a calmer

and more conciliatory note, these

expectations are soon confounded.

Schubert`s final setting of the mass

is comparatively simple and more

compact in its formal design and

harmonic language, allowing the

composer to concentrate entirely on

the questions that concerned him most

of all.

The relatively restrained and terse

Kyrie eschews the traditional

interplay between soloists and choir

and is followed by a Gloria that

presents the listener with an

exceptional wealth of images,

beginning with soaring triplets on the

strings that seem to scale the very

heights of Heaven, only to he cast

back down to earth again. In the

“Domine Deus, agnus Dei", it is not

compassion but the sufferings of the

Lamb of God that are depicted here.

And the rnovement culminates in a

powerful fugue on the words "Cum

Sancto Spiritu", with Baroque element

combining to impressive effect with

Schubert's own individual message.

Vocal soloists are heard for the first

time tn the Credo at the words "Et

incarnatus est... et homo factus est".

Even more than in the A flat major

Mass, Schubert thus focuses attention

on Christ's incarnation, turning it

into the pirece's central concern.

Equally instructive in this context is

the way in which the words are

distributed among chorus, soloists and

orchestra in both these settings.

First heard on the lips of one ol the

two tenor soloists, the "Et incarnatus

est" is wonderfully consoling,

encouraging us to place all our hopes

in Man and, as such, offering an

alternative to this sustained attempt

to come to terms with the

incomprehensibility of the divine and

its undertow of mystery.

As in almost all his earlier masses,

Schubert omits part of the liturgical

text from the vocal line and entrusts

it, instead, to the orchestra as the

voice of absolute music. In doing so,

he not only harks back to the

centuries-old tradition of antiphonal

writing but, at the same time, reveals

himself as far in advance of his time

in propounding this concept of music

as something absolute.

For Nikolaus Harnoncourt, there is no

basis whatsoever to the reproach, so

often levelled at Schubert by writers

on the subject, that his failure to

set the words "Et in unam sanctam

catholicam et apostolicam ecclesiam"

in the Credo reveals an

anti-ecclesiastical bias and might

therefore be taken to imply an

anti-religious outlook on the

cornposer's part: "Ever since they

were first set to music, the words of

the Gloria and Credo have been treated

selectively. It is not true that

Schubert did not set a particular

phrase because he did not believe in

it - that would be an entirely

worthless and false interpretation.

Even Bach and Haydn, whose loyalty to

the church is not in doubt, omitted

individual lines. I should like to

warn listeners against reading too

much into these works on the basis of

what others have written about

Schubert and believing that he wrote

this or that piece only because he

held this or that view, because he

hated his father, because he was gay

or goodness knows what else. I think

that it is Schubert's authentic voice

that we hear rn these Masses. We

should concentrate on the works

themselves. Schubert speaks through

his music, he speaks the language of

music."

The suggestion that Schubert did not

set certain passages of the mass for

ideological reasons becomes completely

untenable when we recall that, with

the single exception of his first

setting of the mass, he never included

the words "Et exspecto

resurrectionem". Yet, if this central

idea were not contained in the music,

the rest of the phrase, "et vitam

venturi saeculi. Amen", would be

completely meaningless.

Schubert's faith finds expression not

only in his sacred works, including

the Gesang der Geister über den

Wassern, with which Harnoncourt

prefaced his performances of both

these Masses in Graz, but also in a

diary entry dated 28 March 1824: "It

is with faith that Man First comes

into the world, and it long precedes

intelligence and knowledge; for in

order to understand anything, one must

first believe in something; that is

the higher basis on which feeble

understanding first erects the pillars

of proof. Intelligence is nothing else

than analysed faith."

Ronny Dietrich

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|