|

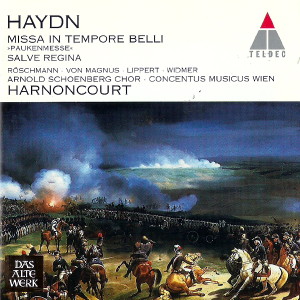

1 CD -

0630-13146-2 - (p) 1997

|

|

| Franz Joseph

Haydn (1732-1809) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Missa in tempore belli

"Paukenmesse" in C major, Hob. XXII:9 *

|

|

39' 28" |

|

| - Kyrie |

5' 46" |

|

1

|

| - Gloria |

10' 35" |

|

2

|

| - Credo |

9' 43" |

|

3

|

| - Sanctus |

2' 16" |

|

4

|

| -

Benedictus |

5' 55" |

|

5

|

- Agnus Dei

|

5' 23" |

|

6

|

| Salve regina in g minor, Hob.

XXIIIb:2 |

|

17' 24" |

|

- Salve

regina

|

8' 01" |

|

7

|

- Eja ergo,

advocata nostra

|

3' 50" |

|

8

|

- Et Jesum

|

5' 53" |

|

9

|

|

|

|

|

| Dorothea

Röschmann,

Soprano |

|

Elisabeth von

Magnus, Mezzo-soprano

|

|

| Herbert

Lippert, Tenor |

|

| Oliver

Widmer, Baritone |

|

|

|

Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

Master *

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Pfarrkirche,

Stainz (Austria) - luglio

1996 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

studio /

live (Paukenmesse)

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 0630-13146-2 - (1 cd)

- 57' 44" - (p) 1997 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Austrian Church

Music in a Post-Josephine Age

The

death of the Emperor Joseph II not

only marked the end of an era in

Austrian history, it ushered in a new

golden age in secular music: the

restrictions on such music imposed by

Joseph were now abolished, and

monasteries and aristocratic dynasties

once again vied with each other in

mounting increasingly elaborate

religious services. With the leading

composers of the day creating a wealth

of sacred works that combined

contemporary stylistic devices with

traditional elements redolent of the

splendours of the Baroque.

At the same time, secular pieces would

often find their way into the sacred

repertory: suitably reworded, famous

arias were performed as motets, and

lengthy instrumental works were

incorporated into the liturgy, notably

as Epistle or Offertory sonatas. This

somewhat free-and-easy approach to

sacred music gave rise to criticism,

not least on the part of

ultraconservative Catholics. Curiously

enough, the greatest offence was

caused by the six great masses that

the universally acclaimed Joseph Haydn

wrote following his triumphant return

from London in 1795. Haydn was

reproached for the fact that the

dominant mood of these works was "not

the solemn seriousness that befits the

temple of the Lord, but profane, naïve

wit and an inappropriate

frivolousness". So seriously was this

criticism taken that his masses came

close to being banned from St Stephens

Cathedral in Vienna.

Missa in tempore

belli ("Paukenmesse")

Following

his return from his second visit to

England in 1795, Haydn resuined his

duties with Prince Nikolaus II

Esterhátzy, one such duty involving

the composition of an annual mass to

mark the name-day of the Princess

Marin Hermenegild. The first of the

composer's six masses intended for

this occasion is believed to have been

the Missa in tempore belli,

which probably received its first

public performance in the Bergkirche

at Eisenstadt on 13 September 1796,

although this has been disputed by the

Haydn scholar, H. C. Robbins Landon,

who suggests that a performance of an

otherwise unnamed work that is known

to have taken place in the Basilica

Maria Treu of the Piarists (otherwise

known as the Piaristenkirche) in

Vienna on St Stephens Day (26

December) 1796 is more likely to have

been the mass’s first official airing.

It emerges from the autograph full

score that the forces that Haydn

originally envisaged were strings,

organ, oboes, bassoon, trumpets and

timpani; clarinets were used only in a

handful of movements, where they

double the oboe parts. But the

discovery of an additional set of

parts with original entries in Haydn's

own hand indicates that the composer

later enlarged the instrumental

forces: clarinets are now found in all

six movements, a flute has been added

to the "Qui tollis" and the trumpets

are now doubled by horns.

The German diplomat, Georg August

Griesinger, who was on friendly terms

with Haydn, reports on the genesis of

the Missa in tempore belli as

follows: "In 1796, at a time when the

French were encamped in Styria, Haydn

wrote a mass to which he gave the

title 'in tempore belli'. In this

mass, the words 'Agnus Dei, qui tollis

peccata mundi' are declaimed in a

curious fashion, with timpani

accompaniment, as though one could

already hear the enemy approaching in

the distance."

Haydn wrote at a time of national

emergency a circumstance reflected in

the score. Napoleon's troops were at

the gates and it was regarded as a

crime punishable by death even so much

as to speak of peace as long as enemy

forces were in the land. For Haydn,

the words of the Ordinary of the Mass

offered a unique opportunity not only

to speak of peace but positively to

demand it with every musical means at

his disposal. This is particularly

clear from the Kyrie, the theme of

which, first stated by the soprano

soloist, is taken up by the choir and

repeated in increasingly urgent

statements, while brief interjections

from the four vocal soloists add to

the sense of insistency. The humble

entreaty, "Have mercy upon us", seems,

on occasion, to be literally

rebellious in tone.

The Gloria is symmetrically

structured, with two thematically

related outer sections, the

superficial festiveness of which is

repeatedly undermined by seemingly

threatening instrumental gestures,

framing an Adagio in A major contested

by bass soloist and choir and invested

with a particularly rapt atmosphere by

the obbligato cello’s mellifluous line

and the writing for the solo flute.

The Credo is launched with a fugue

that gives way to an “Et incarnatus”

of almost oppressive vividness in

which the bass's introduction is taken

up and developed by the other soloists

and choir. It leads directly into the

“Crucifixus” and, thence, to the

ascending scales that herald the

festively joyful "Et resurrexit". A

double fugue with solo interpolations

brings this section of the Ordinary to

an end.

A brief two-part Sanctus is followed

by a more broadly structured and

lyrical Benedictus, which, largely

reserved for the vocal soloists, is

notable for the way in which the music

modulates from C minor to the major at

the word “Hosanna”.

It is in the Agnus Dei, finally, that

we find the famous timpani solo that

has generated so much controversy but

to which the Missa in tempore

belli owes its name in the

German-speaking world - the

"Paukenmesse". A simple melody,

entrusted to choir and strings, is

followed by the muted yet implacable

rhythm of the timpani, which is

accompanied by oppressive syncopations

on the first violins and sustained

notes on the oboes. According to

Haydn’s early biographer, Giuseppe

Carpani, the timpani was to be struck

in the French manner here. The threat

presented by the imminent approach of

war is thus expressed in particularly

striking fashion, climaxing in the

shrill wind fanfare that culminates in

the general outcry on the words “Dona

nobis pacem”.

Haydn was also conscious, of course,

of the psychological effect of the

timpani rhythm, which was intended to

encourage those for whom the drum is

beaten and to inspire fear and terror

in those against whom it is aimed.

Haydn had already tried out this twin

effect in his “Military” Symphony Hob.

I/100, a piece which, by its very

nature, is likewise an anti-war work.

Now it is the timpani that are used,

as it were, to confront God with the

whole appalling horror of war and, by

virtue of its increasingly urgent

entreaties, to force from Him the

peace so desperately longed for.

Salve regina

The last

of the four Marian antiphons, the Salve

regina is sung at the end of

Compline - evening prayers - between

Trinity Sunday and Advent.

17th-century settings often involved

lavish instrumental forces and were

used as motets at Marian feasts.

It is not known for what occasion

Haydn wrote the present Salve

regina in G minor Hob, XXIIIb:2.

It is scored for four vocal soloists,

concertante organ and strings and,

according to a note in the autograph

score, was written in 1771. An organ

solo contained in the same autograph

points in the direction of the Chapel

of the Brothers of Mercy in

Eisenstadt, for which Haydn also wrote

his Little Organ Solo Mass.

The piece is cast in the form of a

large-scale sonata da chiesa

(Adagio-Allegro-Largo/Allegretto) and

acquires charm as a result of its

rhetorical intensity and the

multifaceted variety of the emotions

that it portrays.

Johanna

Fürstauer

Translation:

Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|