|

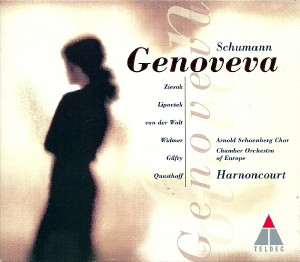

2 CD -

0630-13144-2 - (p) 1997

|

|

Robert

Schumann (1810-1856)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Genoveva |

|

|

|

| Oper in vier Akten - Libretto:

Robert Schumann nach Ludwig Tieck und

Friedrich Hebbel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ouverture |

|

8' 07" |

CD1-1 |

ERSTER AKT

|

|

32' 31" |

|

| - Nr. 1 Chor und Rezitativ:

"Erhebet Herz und Hände" - (Chor,

Hidulfus) |

5' 56" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - Nr. 2 Rezitativ und Arie:

"Könnt' ich mit ihnen... Frieden, zieh' in

meine Brust" - (Golo) |

6' 37" |

|

CD1-3 |

| - Nr. 3 Duett: "So wenig Monden

erst, daß ich dich fand" - (Siegfried,

Genoveva) |

2' 25" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - Nr. 4 Rezitativ: "Dies gilt

uns!" - (Siegfried, Drago, Genoveva, Golo) |

3' 12" |

|

CD1-5 |

| - Nr. 5 Chor: "Auf, auf, in das

Feld!" - (Chor, Genoveva, Siegfried, Golo) |

2' 40" |

|

CD1-6 |

| - Nr. 6 Rezitativ und Szene:

"Der rauhe Kriegsmann!" - (Golo, Genoveva) |

3' 32" |

|

CD1-7 |

| - Nr. 7 Finale: "Sieh da, welch

feiner Rittersmann!" - (Margaretha, Golo) |

8' 09" |

|

CD1-8 |

ZWEITER

AKT

|

|

28' 49" |

|

| - Nr. 8 Szene, Chor und

Rezitativ: "O weh des Scheidens, das er

tat!" - (Genoveva, Chor, Golo) |

8' 15" |

|

CD1-9 |

| - Nr. 9 Duett: "Wenn ich ein

Vöglein wär" - (Genoveva, Golo) |

6' 20" |

|

CD1-10 |

| - Nr. 10 Duett: "Dem Himmel

Dank, daß ich Euch finde" - (Drago, Golo,

Margaretha, Genoveva) |

4' 36" |

|

CD1-11 |

| - Nr. 11 Arie: "O Du, der über

alle wacht" - (Genoveva) |

3' 23" |

|

CD1-12 |

| - Nr. 12 Finale: "Sacht, sacht,

aufgemacht!" - (Chor, Balthasar, Genoveva,

Golo, Drago, Margaretha) |

6' 15" |

|

CD1-13 |

DRITTER

AKT

|

|

25' 53" |

|

| - Nr. 13 Duett: "Nichts hält

mich mehr" - (Siegfried, Margaretha) |

6' 15" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Nr. 14 Rezitativ, Lied und

Duett: "Ja, wart du bis zum jüngsten Tag"

- (Siegfried, Golo) |

9' 51" |

|

CD2-2 |

| - Nr. 15 Finale: "Ich sah ein

Kind im Traum" - (Margaretha, Siegfried,

Golo) |

6' 02" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - Nr. 15 Finale: "Erscheint!...

Abendlüfte kühlend weh'n" - (Margaretha,

Chor, Siegfried, Golo, Dragos Geist) |

8' 54" |

|

CD2-4 |

VIERTER

AKT

|

|

30' 24" |

|

| - Nr. 16 Szene, Lied und Arie:

"Steil und steiler ragen die Felsen" -

(Genoveva, Balthasar, Caspar, Chor) |

11' 00" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - Nr. 17 Szene: "Kennt Ihr den

Ring?" - (Golo, Genoveva, Caspar,

Balthasar) |

5' 35" |

|

CD2-6 |

| - Nr. 18 Rezitativ, Terzett und

Szene mit Chor: "Weib, heuchelt nicht" -

(Balthasar, Genoveva, Caspar, Chor,

Margaretha, Siegfried) |

4' 13" |

|

CD2-7 |

| - Nr. 19 Duett: "O laß es ruh'n,

dein Aug, auf mir!" - (Siegfried,

Genoveva) |

2' 17" |

|

CD2-8 |

| - Nr. 20 Doppelchor: "Bestreut

den Weg mit grünen Mai'n" - (Chor) |

3' 23" |

|

CD2-9 |

| - Nr. 21 Finale: "Seid mir

gegrüßt nach schwerer Prüfung" -

(Hidulfus, Genoveva, Siegfried, Chor) |

3' 56" |

|

CD2-10 |

|

|

|

|

| Rodney Gilfry,

Hidulfus |

Mariana

Lipovsek, Margaretha |

|

| Oliver Widmer,

Siegfried |

Thomas Quasthoff,

Drago |

|

| Ruth Ziesak, Genoveva |

Hiroyuki Ijichi,

Balthasar |

|

| Deon van der Walt,

Golo |

Josef Krenmair,

Caspar |

|

|

|

| Arnold Schoenberg Chor /

Erwin Ortner, Chorus Master |

|

Chamber Orchestra

of Europe

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Gesamtleitung |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Stefaniensaal, Graz (Austria)

- 27-30 giugno 1996 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Wolfgang Mohr / Helmut Mühle /

Michael Brammann |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec - 0630-13144-2 -

(2 cd) - 69' 41" + 58' 23" - (p) 1997 -

DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Reinventing

Opera

|

The

omens could not have been better: on

the one hand, here was a work which,

for more than a century, has

been regarded as no more than a

bizarre curiosity on the very

fringes of the operatic repertory,

while on the other we had a

conductor whose response to

traditional value judgements is

invariably highly personal. The

encounter Genoveva and

Nikolaus Harnoncourt was

bound to be absorbing.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt spent two years

studying the complexities of Robert

Schumann's only opera before he

finally set ahout performing it at the

Graz styriarte in the early summer of

l996. It was while he was casting

round for a large-scale vocal work to

complement his existing recordings of

symphonies and concertos that he

alighted upon the score of Genoveva

and was instantly drawn towards it:

"To begin with, I simply found the

piece very beautiful. It's incredibly

beautiful music. When I started to

look at it in greater detail, I came

across all the withering reviews that

the work has elicited in the course of

the last hundred years. I had the

impression that each critic was merely

repeating what others had written

before him. They had all approached

the piece with a preconceived idea of

what an opera must be like. If it

doesn't live up to one's expectations,

the work itself is condemned out of

hand. But it's the critics themselves

who deserve to be condemned for not

seeing what's on offer here."

For Harnoncourt, Schumann ranks

alongside Schubert and Bruckner are

one of the truly great geniuses of the

l9th century. In consequence, it

cannot be assumed that the composer

was simply trying to gratify ordinary

listener's expectations or conforming

to prevailing conventions and taste.

Like other German Romantic composers,

Schumann was strenuously opposed to

the Italian and French operatic

tradition that predominated at this

time and wanted to see something

altogether different in its place. In

Nikolaus Harnoncourt's view, Schumann

succeeded in "reinventing opera" with

Genoveva.

Steamrollered by Wagner

Composed between 1847 and 1849, Genoveva

initially encountered considerable

interest, not least in the light of

the composer's secular oratorio, Das

Paradies und die Peri, which had

caused a sensation when it was first

performed in 1843. Schumann himself

was regarded as the great hope of

German music and it was naturally

expected that he would write an opera.

Genoveva received its first

performance in Leipzig in 1850, with

Schumann himself conducting the first

two performances. a further production

followed in Weimar in 1855, this time

under Liszt. Only now did the

misunderstandings begin.

At the time that Schumann wrote Genoveva,

the German operatic scene was

dominated by Meyerbeer and Wagner.

Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots had

been unveiled in Paris in 1836 and

soon took Germany by storm, while

Wagner had confirmed his growing

reputation with Tannhäuser in

1845. Schumann himself heard Tannhäuser

in Dresden in 1845 and had been highly

critical of it. At first sight there

appear to be parallels between Genoveva

and Lohengrin (which also

received its first performance in

l850). But these similarities are

superficial in the extreme and go no

deeper than the fact that both works

share the same setting and involve a

crusade.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt is convinced that

Genoveva was designed as a

counterblast to Wagner; who, for his

part, described Schnmann's opera as

"bizarre". Be that as it may, there is

no doubt that Schumann`s attempts to

write a "highly original,

straightforwardly profound German

opera" were undermined by the

all-powerful rivalry of the later

Beast of Bayreuth:

"That’s hardly surprising if you go

about your business with the energy

shown by Wagner. After all, he not

only wrote these works, with that

brilliant knack of his, he was also an

outstanding manager. But Wagner was an

opera composer, whereas Schumann was a

real all-round composer, like Mozart."

It is clear from Schumann's completely

different handling of Wagner's

leitmotivc technique how similar the

aspirations of the two antagonists

were and yet how dissimilar were the

results that they achieved: We're used

to a particular leitmotif

characterising a particular person.

But where does it say that it has to

be like that? Schumann adopted a far

more sophisticated approach. His

leitmotifs are not attached to

individual characters. The whole piece

is built up on a subtly textured web

of leitmotifs, most of which are

derived from a single main motif,

namely, the chorale at the beginning

of the opera, which is later

reinterpreted in a whole host of

different ways. Initially, it stands

on its own, as a devout chorale, in a

positive sense, but it then assumes a

negative aspect, suggesting the sort

of pressure that is placed on the

people. Later still, it becomes a

portrait of Golo, presenting him as a

positive figure, after which the motif

is transferred to Genoveva herself.

Inevitably, this provides tremendous

links between the different

characters. By being used in the most

varied combinations, these motifs do

not express a particular character but

suggest, rather, the infinite range of

possibilities contained within any one

character. I find it particularly

interesting that all the motivic

figures already appear in the Overture

and that there is something

intaglio-like about them, allowing the

listener to register them clearly."

A Symphonic Floodtide as a River of

Fate

In Nikolaus Harnoncourt's view, the

special place that Genoveva

occupies in Schumann's works is clear,

not least, from the amount of time and

energy that he expended on the piece:

"At no point before or later did he

devote himself to a subject with the

same segree of intensity that he gave

to Genoveva. For him, Genoveva

was the ultimate gial to which he

aspired as a composer. But the work

was already misunderstood even during

the 19th century. Listeners expected

things that it simply did not contain.

There is no dialogue nor any

psychological development. The

characters do not talk to each other

but only speak about themselves. They

are magical monologues. I can well

imagine all the characters as

different facets of a single complex

character.

"Genoveva is a psychological

fdrama, completely unclassical,

thoroughly modern, almost absurdist.

It raises questions but without

offering any answers. It does not set

out to moralise but only to show us

something. You cannot cure what is

incurable. Schumann was concerned to

depict inner states, to suggest the

inevitability of certain events in his

characters' lives and to show the

point at which it is no longer

possible to avoid being sucked under.

You can't speak of guilt or morality

here. Things sumply happen.

"The music embodies this all-consuming

flood of emotions. The dialogue is not

realistic: it is not the sort of text

that the music reinforces and

elucidates. Here the composer attempts

to forge a completely new link between

the individual word and its

corresponding note: the text triggers

the music, which is why Schumann had

to write his own libretto, allbeit

borrowing heavily from existing plays

on the subject by Ludwig Tieck and

Friedrich Hebbel. The surreal element

is already very prominent in Tieck.

"The orchestral forces are fairly

constant from the first notes of the

Overture right through to the end of

the opera. Schumann varies his forces

very little - clearly a conscious

decision. The piece is like a great

symphony with voices. There are some

wonderful colours, every detail is

incredibly finely honed, but the full

orchestra is used virtually all the

time. This symphonic floodtide seems

to me like a river of fate. In this

way, the implacable passage of time in

the music - the fact that you can

never turn it back, never make it stop

- becomes a dramaturgical principle."

The Genoveva Theme in German

Romanticism

Genoveva is the young wife of the

Count Platine, Siegfried. During his

absence on a crusade, their new

steward, Golo, presses his attentions

on her and, his impassioned advances

having been spurned, accuses her of

adultery. Siegfried condemns her to

death. The servant ordered to kill her

takes pity on her and abandons her to

her fate in a rocky wilderness. For

seven years she remains in the forest,

keeping herself and her new-born

infant, Schmerzenreich, alive by

eating herbs and drinking the milk of

a hind. Siegfried belatedly discovers

that she is innocent and, coming upon

her while out hunting, takes her back

to his castle.

French in origin, this popular legend

exists in countless different versions

and many iconographical

representations. It first appeared in

Germany in the 17th century. Many

adaptations followed, and by

Schumann's day the subject was widely

known.

The two plays that inspired Schumann's

opera, Ludwig Tieck's Leben und

Tod der heiligen Genoveva (1800)

and Friedrich Hebbel's Genoveva

(1843), are based only loosely on the

theme of the crusades and on the

religious ideas bound up with them. In

their different ways, both playwrights

succeeded in bringing out the human

conflicts contained within the story

and keeping those conflicts on a short

fuse by concentrating on the way in

which the characters are hopelessly

embroiled in fateful relationships.

Events follow one another with an

inevitable logic, with evil, too,

obeying its own inner laws. Guilt is

no longer a moral category: we are

guilty because we exist. "Thus time

passes us by, coldly and

indifferently," wrote Tieck. "It knows

nothing of our anguish, nothing of our

joys, it leads us by its icy hand.

[...] It is the stars that ordain our

fate and make us virtuous or vicious,

so that care, sorrow and remorse are

folly pure and simple."

Fron a present-day perspective such

thoughts seem almost existentialist in

character. Nikolaus Harnoncourt, who

has studied the literary sources in

detail, blames old prejudices for the

fact that critics have been taken in

by the courtly trappings of Schumann's

opera and, by neglecting to look

behind its superficial setting, have

failed to appreciate its true

modernity:

"The piece is really quite

frighteningly complex. Who decides

what is sacred, what is diabolical?

Who is guilty? Who is innocent? This

is something that the Romantics, then

and now, understand. On a latent

level, there is also a pronounced

psychoanalytical element. Take the

mirror scene in the third-act finale:

the magic mirror reveals the blackest

depths of the human soul, where doubt

and distrust tale root. And then there

are Siegfried and Golo, who can be

seen as complementary characters: the

former is a man of experience, a man

lacking in imagination, with a

character that fits this cliché like a

glove, while the latter, by contrast,

has all the brilliant qualities and

talents that the former lacks. At the

same time, Golo is literally

worshipped by the petty bourgeois

Siegfried. You can follow all this

marvellously through the leitmotifs.

You could say that these two embody

the self and longing.

"There isn't a trace of neo.medieval

Romanticism. Although Schumann gives a

clue as to when the action takes place

- right at the beginning there is a

reference to Charles Martel, and he

uses the departure and return of the

crusaders as an outer framework for

the action - he none the less insisted

that 'the time at which the piece is

set is poetic time'."

The Composer as Librettist

It was originally the Dresden man of

letters Robert Reinick who was to have

produced a libretto for Schumann by

conflating the versions of Tieck and

Hebbel. When he ran into difficulties

with Reinick, Schumann turned to

Hebbel in person, but, as a

self-confessed non-musician, Hebbel

was unable to feel his way into the

composer's imaginative world. At this

juncture, Schumann began to wonder

whether he himself might be qualified

to write his own libretto: as the son

of a bookseller and publisher, he had

been familiar with the world of

letters from an early age, while his

profound admiration for Jean Paul,

which had left its mark on his

adolescence, had increased his

literary competence to the point where

he had long felt that he was more of a

writer than a musician. After all,

Schumann had made a name for himself

much earlier as a writer than as a

composer, not least as a result of his

highly regarded publications in the

pages of the Neue Zeitschrift für

Musik, which he had founded in

1854 with other members of his “League

of David”. The German novelist Peter

Härtling paints a graphic picture of

this well-developed dual talent in his

recent biographical romance, Schumanns

Schatten.

The fact that, in the case of Genoveva,

Schumann was his own librettist

undoubtedly adds to the work's

fascination - as long as listeners are

prepared to accept his 19th-century

idiom on its own terms. This is also

true of many of the other German

Romantic opera librettos that are

nowadays routinely dismissed out of

hand - although Wagner; curiously,

remains the great exception. According

to Nikolaus Harnoncourt, “There is

something almost cruel about not

taking seriously the people of this

period simply because of their

language and about falling around

laughing at that language. Schumann,

Schubert and Weber - all these

composers had a great appreciation and

understanding of language, all of them

were active in men of letters. I can't

laugh at the language of Lohengrin,

I can feel only despair. But people

lap it up!"

The events recounted in the French

legend retailed above have been

tolescoped together and substantially

altered in the second part of

Schumann's libretto. Here there is no

mention of the child that Genoveva

brings into the world and that

provides an additional conflictual

element in the versions of Hebbel and

Tieck. Conversely, the figure of

Margaretha - a composite of nurse and

witch - is of decisive dramaturgical

importance.

"With Schumann," Nikolaus Harnoncourt

notes, "the piece ends seven years

earlier. Cutting off the story in this

way makes the characters even clearer

and ensures that the situation is

brought into greater focus. Siegfried

is now immediately prepared to believe

that Genoveva has been unfaithful.

Schumann allows him to stumble

straight into his behavioural

patterns. Since there is absolutely no

question of the child's father, there

is not the slightest shadow of a doubt

cast over Genoveva's faithfulness."

Monika

Mertl

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|