|

1 CD -

0630-13137-2 - (p) 1997

|

|

| Johannes

Brahms (1833-1897) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Concerto for Violin and

Orchestra in D major, Op. 77 |

|

36' 49" |

|

| - Allegro non troppo (Cadenza:

George Enescu) |

21' 01" |

|

1

|

| - Adagio |

8' 13" |

|

2

|

| - Allegro giocoso, ma non

troppo vivace |

7' 35" |

|

3

|

| Concerto for Violin,

Violoncello and Orchestra in A minor,

Op. 102 |

|

32' 19" |

|

- Allegro

|

17' 30" |

|

4

|

| - Andante

|

6' 06" |

|

5

|

| - Vivace non troppo |

8' 43" |

|

6

|

|

|

|

|

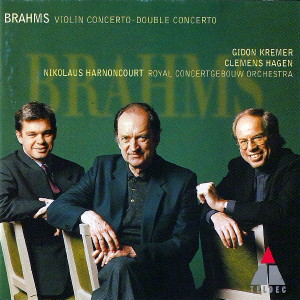

| Gidon

Kremer, Violin |

|

| Clemens

Hagen, Violoncello |

|

|

|

| Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Het

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam (Olanda) -

marzo 1996 (Op. 77), aprile 1997 (Op.

102) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 0630-13137-2 - (1 cd) - 69' 21" - (p)

1997 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Two very

different concertos for Joseph

Joachim

|

“Look at

virtually any picture of

Brahms and you see a fat man,"

he says. "Of course, I carft

say how mach that influences

your way of approaching

his music, but too often

Brahms is played in a rather

'fat' fashion. One forgets

that inside this ample person

was a very fragile soul, and

yer it can be diffcult

to transfer from what seems

like mere physical weight to

fragility warmth and

striving after the inexpressible.

Brahms is too often considered

a sort of throned

monument, looking dawn on the

romantic world; a mighty

academician, the heavyweight champion

of composing." Gidon

Kremer

"I feel

that the musical language of

the Double Concerto rnakes it

clear that Brahms conceived it

as a gesture of sympathy and

reconciliation between him and

his musician friend. This idea

offers a very interesting

basis for an interpretation,

since dialogue is such a

fundamental element,

especially in a double

concerto. I have found ideal

partners for this conversation

in Nikolaus Harnoncourt and

Gidon Krerner. With its

important cello part, the work

stirs a craving for more. I

shall always regret that

Brahms didn't

write a 'genuine' cello

roncerto." Clemens Hagen

----------

Johannes

Brahms’s violin works are

closely connected to his

friendship with Joseph Joachim,

the leading violin virtuoso of

his time. Just as Brahms

submitted many of his piano

works to Clara Schumann for her

criticism and suggestions, so

did he take the advice of his

friend Joachim with regard to

violin pieces, the more so as he

did not play the violin himself.

Brahms composed the Violin

Concerto op. 77 in the idyllic

town of Pörtschach

on the Wörthersee

in the summer of 1878 and

presented it to Joachim for his

evaluation. The intensive

exchanges that ensued resulted

in the elimination of the second

and third movements, which were

replaced by the Adagio we know

today. Brahms thus turned an

originally four-movement

concerto into a three-movement

one. The work was dedicated to Joseph

Joachim and premièred in Leipzig

on 1 January

1879 with

the dedicatee as soloist and the

composer conducting. In spite of

frequently voiced objections to

the work’s purportedly overly

symphonic and insufficiently

violinistic character, this

concerto quickly conquered the

world’s concert halls and is

part of every great violinist's

repertoire today. Bronislaw

Huberman was even able to claim

the particular privilege of

having moved Brahms to tears

with his playing as a

l3-year-old prodigy.

Brahms ultimately left the

cadenza entirely up to his

friend Joachim. Although this is

the one that is generally played

today, other cadenzas have been

written for this work by

renowned violinists such as

Leopold Auer and Fritz Kreisler, and even by

the piano virtuoso Ferruccio

Busoni. In

this recording, Gidon Kremer

plays the cadenza written in 1903 by George

Enescu. In 1894,

when he was 13,

Enescu met Brahms in Vienna and

played at the third desk of the

violins in a performance of

Brahms's

First Symphony conducted by the

composer. The Romanian violinist

and composer taught Yehudi

Menuhin, among others, and many

of his works are now being

performed for the first time in

many years, such as the opera Oedipe

or the Impressions

d'enfance

op. 28

for violin and piano, which

Gldon Kremer recently recorded

for Teldec.

The first movement of Brahms’s Violin

Concerto makes it clear that the

solo violin is merely one

instrument among many, albeit an

important one. It is delicately

interwoven into the orchestral

texture and alternates between playing the

melodic lead and the

accompaniment. Its

first entrance is preceded by a

tranquil theme in the low

strings and winds which acquires

a spatial dimension through its

descending and ascending triadic

melody before ending on the

dominant. The music is propelled

forward by canonic entries and

syncopations, and spun out in a

delicate chamber-style writing

until it reaches the contrasting

second theme with its sharply

accented dotted sixteenth notes.

Now, at last, the solo violin is

allowed to make its entrance

with exuberant figurations

before it, too, takes up the

main theme. The tendency to

treat the solo violin as a

primus inter pares is even more

pronounced in the slow movement.

Pablo de Sarasate allegedly said

that he would not even think of

listening to the oboe play the

only melody in the piece while

he just stood there, idly

holding his violin. The movement

begins with a songful oboe melody

accompanied solely by the

woodwinds. The solo violin also

states the melody, but "only" in

an embellished version. This

tripartite movement is

predominantly placid, though its

middle section is harmonically

quite bold. The violin describes

melodically and rhythmically

polished arches and pours forth

an almost inexhaustible, endless

flow of melody.

As in a

number of other finales in

Brahms’s works, the last

movement of the concerto evokes

Hungarian folk music, but in a

way that defies a precise

identification with any specific

models. Hungarian-sounding musical

traits are frequent in the 19th

century and can be found in

Johann Strauß's Die

Fledermaus as well as in

works by Franz Liszt. However,

research conducted in the 20th

century, especially by Bartók and Kodály, has shown

that the topos of Hungarian folk

music actually has its roots in

the music of nomadic gypsies. In

Brahms's Violin Concerto, the

melody in thirds, the cimbalon

accompaniment suggested in the

strings and the downward-leaping

syncopation can be identified as

“Hungarian” musical

characteristics. The solo violin

has a more pronounced role here

than in the preceding movements

and keeps rushing forward to

take the lead with the rousing

main therne. However, here too

the symphonically differentiated

orchestral writing and the

lyrical points of rest within

the surging flow of the rondo

show that Brahms was aiming to

produce more than simply a

folkloric

effect.

Brahms’s last orchestral work,

the Concerto for Violin,

\/ioloncello and Orchestra op. 102, is even

more closely connected with

Joseph Joachim than the Violin

Concerto, not only in a musical

sense, but also with respect to

the personal relationship

between the two artists and

friends. Their friendship had

cooled considerably after Brahms

took the side of Joachim's wife Amalie

in a marital dispute between the

couple. Both Brahms's biographer

Max Kalbeck and Clara Schumann

interpreted the work as an

attempt to restore the

friendship. Clara wrote in her

diary: "It

is a thoroughly original work.

This concerto is, in a sense, a

gesture of reconciliation -

Joachim and Brahms have spoken

to each other again for the

first time in years."

Written in Thun in 1887, the

concerto was premièred at

Cologne's Gürzenich

Hall on 18

October 1887

with Joachim and the cellist

Robert Hausmann playing under

Brahms’s direction. The

composer's wish for

reconciliation was apparently

fulfilled. Although Brahms's

relationship with Joachim was the

outward occasion

for the work, it is also

reflected in the composition

itself. It

is more than plausible to see

the two friends in the interplay

of the solo instruments and to

interpret the duet in thirds in

the epilogue of the last

movement as a final peacemaking.

Brahms even alludes to his

friend in the notes of the theme

by quoting the motto F-A-E in

the main theme of the first

movement. This

is the motto Joachim

had chosen for his own life and

which both friends shared:

“Frei, aber einsam" (free but

lonely). Brahms never married and, after an

ill-fated love affair and his

intense closeness to Clara

Schumann, he gave up all hope

ofa lasting relationship. In a

letter written in l887, the year

he composed the Double Concerto,

Brahms wrote: "I

need absolute solitude not only

in order to accomplish what I am

capable of, but basically in

order to think at all about my

own affairs. That is part of my

nature, but is also easy to explain... Whoever,

like

myself, enjoys life and art

beyond that of his own making is

only too tempted to enjoy both - and to forget other

things. Perhaps it is also the

brightest and most correct thing

to do. But now that a large new work looms before me.

I am really quite happy about it

and must tell myself: I would

never have written it if I had

been enjoyng myself so

wonderfully on the Rhine and in

Berchtesgaden."

There are different versions of

some solo passages, which

suggest the influence of Joachim's

proposals. Certain passages from

hitherto

unpublished

versions have been selected for this

recording.

More so

than the Violin Concerto, the

Double Concerto unfolds a

chamber-music texture over broad

stretches. This also results

from the importance attributed to the

two soloists, who yield to the

orchestra only 60 of the 340

bars of the

last movement. Ensuing from his

own experience

as a pianist and chamber

musician, Brahms’s

concept requires the musicians - soloists and

orchestra - to interpret all the

subtle shadings

and to listen

very carefully

to each other. Brahms thus wrote

two concertos

for the virtuoso Joseph Joachim

in which the soloist was

required to fulfill a completely different

role from that which was

expected from

a concerto soloist in the 19th century. No

wonder that even the critic

Eduard Hanslick, an avowed

friend of Brahrns, maintained

certain reservations about the

work. Fortunately, history has

proven him wrong.

Andreas Richter

Translation:

Roger Clement

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|