|

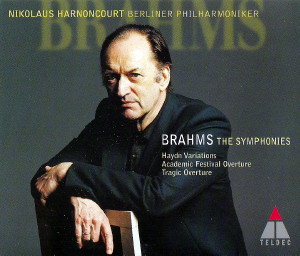

3 CD -

0630-13136-2 - (p) 1997

|

|

| Johannes

Brahms (1833-1897) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Variations on a Theme by

Joseph Haydn in B flat major, Op. 56a |

|

18' 18" |

|

| - Chorale St. Antoni: Andante |

2' 09" |

|

CD1-1

|

| - Var. I: Poco più animato |

1' 27" |

|

CD1-2

|

| - Var. II: Più vivace |

1' 04" |

|

CD1-3

|

- Var. III: Con moto

|

1' 55" |

|

CD1-4

|

- Var. IV: Andante con moto

|

2' 07" |

|

CD1-5

|

| - Var. V: Vivace |

1' 04" |

|

CD1-6

|

| - Var. VI: Vivace |

1' 20" |

|

CD1-7

|

| - Var. VII: Grazioso |

2' 28" |

|

CD1-8

|

| - Var. VIII: Preto non troppo |

1' 10" |

|

CD1-9

|

| - Finale: Andante |

3' 35" |

|

CD1-10

|

| Symphony No. 1 in C minor,

Op. 68 |

|

47' 35" |

|

- Un poco sostenuto -

Allegro

|

17' 07" |

|

CD1-11

|

| - Andante

sostenuto |

8' 30" |

|

CD1-12

|

| - Un poco Allegretto e

grazioso |

4' 53" |

|

CD1-13

|

| - Adagio - Più Andante -

Allego non troppo, ma con brio |

17' 06" |

|

CD1-14

|

| Symphony No. 2 in D major,

Op. 73 |

|

45' 27" |

|

| - Allegro non troppo |

21' 06" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Adagio non troppo |

9' 01" |

|

CD2-2 |

| - Allegretto grazioso (Quasi

andantino) - Presto ma non assai |

5' 35" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - Allegro con spirito |

9' 47" |

|

CD2-4 |

| Tragic Overture in D minor,

Op. 81 |

|

14' 20" |

CD2-5 |

| Academic Festival Overture in

C minor, Op. 80 |

|

10' 26" |

CD2-6 |

| Symphony No. 3 in F major,

Op. 90 |

|

37' 00" |

|

- Allegro con brio

|

13' 33" |

|

CD3-1 |

| - Andante |

8' 16" |

|

CD3-3 |

| - Poco Allegretto |

6' 25" |

|

CD3-3 |

| - Allegro |

8' 46" |

|

CD3-4 |

| Symphony No. 4 in E minor,

Op. 98 |

|

40' 24" |

|

| - Allegro non troppo |

12' 30" |

|

CD3-5 |

- Andante moderato

|

11' 18" |

|

CD3-6 |

| - Allegro giocoso |

5' 53" |

|

CD3-7 |

| - Allegro energico e

passionato |

10' 43" |

|

CD3-8 |

|

|

|

|

| Berliner Philharmoniker |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Philharmonie,

Berlino (Germania) - dicembre 1996 (CD

1), marzo & dicembre 1996 (CD 2),

aprile 1997 (CD 3) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

live /

studio (Tragic Overture)

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 0630-13136-2 - (3 cd) - 66' 05" + 70'

33" + 77' 36" - (p) 1997 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

"It's like

scratching lots of patina off

old statues"

|

Nikolaus Harnoncourt

talks to Walter Dobner.

Walter

Dabney: Herr

Harnancourt, it is striking,

is it not, that Brahms

completed his

four symphonies within the

space of barely a decade,

a period that, even so,

amounts to about a quarter

of his entire creative

career. If you also

include the period of

nearly a decade and a half

that he needed to complete

his First Symphony, you

end up with a total of

twenty-five years during

which the symphony was one

of Brahms's main

concerns as a composer.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt:

It’s

a matter of some amazement

that there were only four

symphonies in the end. There

is no doubt that the

enormously protracted

genesis of the First

Symphony was bound up with

Brahms’s mental outlook. He

must have been very precise

as a musician and artist and

must have worked with what I

am tempted to call “Gothic

precision". I am reminded of

statues in Gothic churches

on which the sculptor has

elaborated every last detail

even in those areas that you

can be

absolutely certain will

never be seen, A Baroque

artist would never do that

but would simply nail on a

couple of wood mouldings. I

see a certain similarity

between this Gothic

perfection and Brahms's

attitude to his work. This

meticulousness, this

scrupulousness, this sense

of "Is

that really what I meant?“ -

it is this that always

strikes me as so North

German about him. As a

result, it is really not

possible to say with

ultimate certainty whether

what appeared in print under

Brahms’s extremely careful

supervision was his final

word on the subject or

whether it was only for some

other, more practical reason

that he departed from his

earlier version.

If we could take a closer

look

at the genesis of the

First Symphony, which

finally received its first

performance in Karlsruhe

on 4 November 1876, it is

curious that Brahms had

already completed the

original version of the

symphony's first movement

when he told the conductor

Hermann Levi: "I'll

never write a symphony." Equally

remarkable

and widely discussed are

the numerous references to

Beethoven contained in

this piece.

We also know that Brahms

felt a sense of despair at

the thought of Beethoven's

spirit standing at his

shoulder and shaking his

head at every note that he

wrote. At the same time,

Brahms couldn’t bear to be

told by everyone that his

First Symphony was

"Beethoven’s Tenth". He

didn’t like it, even though

he had done everything to

ensure that people felt like

that.

It

was the conductor Hans von

Bülow

who rnade this remark

about "Beethovens Tenth",

but you’d agree, I think,

that it has done more harm

than good In the work's

reception history.

Undoubtedly. But I do

believe that the major

influence here was Schumann

- not Clara, but Robert. I see

very many parallels between

them and regard Schumann

almost as a mentor here.

One of the first people

to get to know the C minor

Symphony was Clara

Schumann, and it is she

who is reported to have

said: “I miss the melodic

drive, however thoughtful

the writing is otherwise."

In saying this,

she was expressing a

belief to which many

people would still subscribe

today: Brahms - they argue

- had few ideas, but the

few that he had he

invariably developed to

rnasterly effect. Do you

share this opinion?

The term "idea" always makes

one think of melodic ideas.

But for a composer with an

eye for the past, melodic

ideas were not at all

important, they could be

picked up anywhere. It

was only during the

compositional process that

the real work began, when

the initial idea was

developed. One of the most

radical examples of this is

Beethoven. I doubt whether

anyone would describe

Beethoven’s melodic ideas as

anything to get worked up

about: presumably even he

himself found them of

minimal interest. And the

same is true, I think, of

Brahms. When Brahms was

working on his Second

Symphony on the Wörthersee,

he commented

enthusiastically on

Carinthian tunes. As all

Carinthians know, their

country is full of tunes

which, however banal, are

none the less very moving.

Not that I’m

suggesting that Brahms had

to go to Carinthia in search

of his tunes. It would be

wrong to look for melodic

ideas in Brahms. What

matters is that the themes

that he finally found and

the things that he does with

those themes are really

quite magnificent. The way

in which Brahms constructs

and fashions his slow

movements out of virtually

nothing is incredible!

It's

interesting that even in

his First Symphony Brahms

is already fully developed

as a symphonic composers.

The main action takes

place in the two outer

movements, there is no

scherzo and the two middle

movements are

intermezzo-like in

character.

The middle movements have

always been criticised.

Brahms himself finally began

to have doubts about their

effectiveness and kept

changing their order. For my

own part, I see in these two

inner movements essential

aspects of his symphonies in

general. The opening

movement and the finale

obviously both leave a deep

impression and were

presumably Brahms’s

principal concern, but, at

the same time, it is

impossible not to marvel at

the total originality of

these middle movements,

which do not really reflect

the Classical view of the

symphony and where it is not

at all clear which of them

Brahms saw as a substitute

scherzo.

You have already alluded

to the fact that Brahms

had barely sent off his

First Symphony to his publisher,

Fritz Simrock, at the end

of May 1877

before he started work on

his Second Symphony, most

of which was written

in

Pörtschach

on the Wörthersee.

“The Wörthersee is virgin

soil, there are melodies

everywhere," Brahms told

his friend, Eduard Hanslick.

But when he sent off the

score to his publisher in

November 1877, it was with

the words: “The new

symphony is so melancholy

that you won't be able to

bear it."

How would you yourself

characterise the basic

mood of this ”Pörtschach

Symphony", which is often

seen as a serenely relaxed

and lyrical counterpart to

the C minor Symphony?

I think that, intentionally

or by chance, Brahms - like

Beethoven - wrote his

symphonies in pairs. It’s

like a conversation between

two intelligent, like-minded

friends. One of them says

something, and then the

other -

even if he agrees with it -

will begin by expressing his

doubts. Only after a lengthy

discussion, during which

their own positions may not

even be represented but may

be replaced by something

almost amounting to

role-playing, do they reach

a conclusion. That, in my

own view, is the aim of any

discussion. And this is very

much the situation in which

any composer inevitably

finds himself whenever he

works on a piece since he is

always having to take

decisions. From this point

of view, it seems to me

entirely reasonable that a

composer setting out to

write another symphony

should produce a companion

piece designed to

counterbalance his first.

This is the case with all

four of Brahms’s symphonies.

I believe that they were

designed in pairs, as,

indeed, were Beethoven's

-think

of the Fifth and Sixth, on

the one hand, and the

Seventh and Eighth on the

other.

The most interesting

section of the Second

Symphony is arguably the

third movement, a

five-part Allegretto

grazioso based on a single

thematic cell. The German

musicologist Constantin

Floros

has compared it with an

early Baroque suite.

This third movement is very

similar to a section of a

suite. Brahms’s recourse to

early Baroque and

Renaissance elements is an

important aspect of his

symphonies and reveals him

as the avid library-user

that he was. In the Fourth,

for example, I can

hear Gabrieli - in the

second movement. And I sense

Henry Purcell in the Haydn

Variations. Also, Brahms

took an intense interest in

French Baroque music and

even had special characters

cast,

since he thought that the

signs that Couperin used for

the ornaments in his own

works could not be realised

by any of the other signs in

use in Brahms’s day. The

third movement of his Second

Symphony is a kind of

derivative fast minuet. It

was clear to Brahms that a

minuet could be a very slow,

stately dance movement, like

the famous minuet in

Mozart's Don Giovanni,

but that it could also be

terrifically fast, like the

scherzos in Beethoven's

symphonies. (These last-named

movements do not, however,

come from nowhere, but are

modelled on late passepied

minuets.) The opening

movement of the Second

Symphony is likewise a kind

of minuet. This similarity

between the movements was

not unimportant for Brahms.

It seems to me that he would

write a whole symphony

around a single idea.

Another remarkable aspect

of this Allegretto

grazioso is its

instrumentation: Brahms

dispenses not only with

trumpets, trombones

and bass tuba here but

also with the timpani.

Even more remarkable, it

seems to me, is the fact

that Brahms uses a bass tuba

at all here, but the reason

for this, I think, is the

second movement, the theme

of which takes off in the

third bar with a

chorale-like passage that

Brahms underscores by means

of tuba and trombones. For

me, this suggests not only

that Brahms wanted to

express a sense of

awesomeness here but also

that he did not have access

to what were then the

brand-new, large-bore

trombones and tubas, since

it is impossible to obtain a

proper balance with these

newer instruments. I may

say that I

think that the beginning of

this Adagio non troppo is

always played too loudly,

since people no longer

understand Brahms’s

dynamics: pf means poco

forte, which is very

close to piano. The

presto sections in

the third movement are like

the trios in a minuet and,

as with the Menuetto from

the First Brandenburg

Concerto, are all in

different time-signatures. I

do not regard this

Allegretto grazioso as a

Baroque suite, but as a

group of movements or, to

put it in more concrete

terms, as a minuet with the

usual trios, as you often

find in French Baroque music

- in

Marais, for example.

The Third Symphony was

completed in Wiesbaden in

1883 - the year in which

Wagner died and Bruckner

completed his Seventh

Symphony - and it

encouraged Clara Schumann

to wax particularly

effusive: "What

a work, what poetry, the

most harmonious mood runs

through it all, all the

movements are part of a

unified whole, pulsating

with life, every movement

a jewel." Antonín

Dvořák,

too, thought very highly

of the piece. None the

less, the F major Symphony

continues - incornprehensibly

- to be overshadowed by

the composer's other

symphonies.

I couldn’t agree with you

more. For me, it’s a central

work. As for Brahms’s

comments to his publisher

and friends, I`ll

say only that, in my own

view, he was a bit of a lad

- as both man and artist -

and that he enioyed

misleading people. When he

announced his symphonies and

described what they would be

like, everyone expected

something very specific, but

what emerged was always very

different. His Italian

performance markings in his

autograph scores similarly

remind me of student jokes -

he would invariably write smorzando

with schm- for example,

suggesting affinities with

the German verb "to roast or

swelter”.

Brahms was fifty when he

wrote his Third Symphony.

Fifty is an age when

people often take stock of

their lives, and this may

well have been the case

with Brahms, too.

Certainly, it is striking

that the opening movements

central motif consists of

the notes F-A flat-E, a

motif which writers on

Brahms have sometimes seen

as a minor-key

variant of the young Brahms's motto,

F-A-E, "Frei, aber einsam”

- "free,

but lonely".

To be honest, that had never

occurred to me. You’re the

first person to tell me

that. For a work to begin in

F major but for the major

tonality to be immediately

clouded by the introduction

of the minor third is, of

course, unusual, but the

sequence F-A flat-F really

becomes interesting only

when the A finally enters. I

think Brahms had far more

feel for tonality than the

vast majority of composers

at that time. This was the

result not so much of the

pitch and state of the

instruments as of the purity

of the chords. To be banal,

F major reminds me of

Christmas. It is

what we strive for: perfect

happiness, purity, beauty.

When the very second chord

in a symphony in F major

introduces a note of pain

and does so, moreover, in

such a subtle way, then

that, for me, is where the

heart of that work is to be

found. It

is the way in which Brahms

finally reaches the note A

with the F major chord at

the end of the final

movement that makes this

work, for me, one of the

most beautiful and

overwhelming in all music.

No less interesting about

Clara Schumann's remark is

that the work is "a unified

whole". More than in any

other symphony, Brahms seems

to have taken up Schumann's

idea of ensuring that the

movements form a single

entity. He even goes a stage

further in that all four

movements are not only

closely interrelated in

terms of their tonalities

but also motivically

interconnected. Normally, I

would not attach much

importance to such

considerations, but in this

particular case, all the

movements are related to F

major and to that extent

form a unified whole.

Moreover, the final

note

of one movement is always

the first note of the next.

By way of comparison, it is

worth recalling that in the

case of the First Symphony

the last three movements all

begin on the third of the

chord with which the

previous movement ends.

If

we can turn now to the

Fourth Symphony which was

first performed in

Meiningen on 25 October

1885, Brahms once said:

"The thing that people

call 'invention', in other

words, a genuine idea, is,

as it were, a farm of

higher inspiration, which

means that there is

nothing I

can do about it." A good

example of this is his

conception of the first

movement of this symphony

which is based, in

essence, on the idea of a

descending third, but

equally symptomatic

in this respect is its

final movement,

a passacaglia, the theme

of which is combined

with the final chorus

from Bach's

cantata BWV 150, Nach

dir, Herr, verlanget mich.

As before, the Fourth's

finale reminds me of

French Baroque music.

Whatever influence Bach’s

cantata may have had on

this final movement, the

passacaglia’s set of

variations, the varied

instrumentation and

timesignatures and even

its dramaturgical

structure are closely

modelled on opera finales

by Rameau and Marais, in

other words, on music

written during the first

half of the l8th century

and thoroughly familiar to

Brahms. There were

presumably various reasons

for this: there may have

been lots of scores by

French composers in the

libraries to which Brahms

had access; and Eusebius

Mandyczewski, the

archivist at the

Gesellschaft der

Musikfreunde in Vienna, or

another of Brahms’s

friends may have been very

fond of this music. (It

is certainly no accident

that Brahms was interested

in Couperin in particular

and later edited some of

his works.) This is the

music of the great

orchestral passacaglias

that simply do not exist

in German Baroque music.

When I

first played this symphony

with an orchestra -

it was with the Vienna

Symphony in 1952

-,

I

was immediately reminded

of Forqueray's viol

sonatas. Like so much else

by Brahms, this movement,

too, is made to sound

unduly monumental in

modern performances.

Throughout its performance

history, each generation

has added new layers to

it, so that it is now

difficult to get back to

the actual piece. Even the

orchestral resources and

dynamics are affected in

this way. Brahms writes by

no means as many fortissirnos

and triple fortes

as tend to be played. He

very often writes forte,

and in each case one could

add: "Only forte, nothing

more.” This poco forte

that Brahms so often uses

to re-establish the

simplicity that he was

striving for implies a

process like that of

scratching off lots of the

patina from old statues

and pieces of furniture.

If you listen to

historic recordings by

performers who were in

contact with Brahms's circle,

you find that they sound

completely different

from the Romantic

interpretations of the

lost fifty years. To

what do you attribute

this?

I attribute it to the

constant and, arguably,

necessary change in

fashion. A work is in a

state of flux from the

moment it leaves the

composer's desk. Only very

briefly are its composer’s

original intentions fully

realised -

perhaps for ten years,

perhaps even less, and

often only in the

composer's most intimate

circle. You can see this

quite clearly in the case

of Beethoven's symphonies.

Within twenty years of

Beethoven's death an

irreconcilable struggle

had already broken out

between Mendelssohn and

Wagner over the question

of tempi -

should they be "fast" or

“slow"?

- and over an

interpretative approach

that played off the "emotional"

against the “unemotional".

The same is true of all

composers, and I

believe it is both natural

and necessary. The

relationship between one

generation of interpreters

and the next is like that

between two intelligent

friends whose discussions

inevitably spark off an

argument simply because

they feel the need to

adopt differing views,

even though they do not

really occupy differing

standpoints. If a

conductor and orchestra

perform a piece in a

particular and highly

convincing way for one

generation, then this

interpretation at the same

time encourages dissent

and begs the question why

it has to be played in one

way and not another. This

is sometimes demonstrated

particularly clearly, as

with such strikingly

different performers as

Furtwängler

and Toscanini. This kind

of dialectic is found both

in the creative process

itself and in the way in

which works are

interpreted. While I

was teaching at the

Salzburg Mozarteum, I

would sometimes play the

students old gramophone

recordings. What

interested me most - and

sometimes also drove

me to despair - was

the way in which the taste

and aims of one generation

(in other words, what one

might describe as

yesterday's fashion) were

always treated with contempt

by the next. And yet anyone

who listens seriously will

recognise approaches which,

important and interesting

though they undoubtedly are,

nowadays tend to be

overlooked since today's

performers are following

another trend. We need to be

clear in our own minds that

the same will happen to our

own readings in twenty or

thirty years’ time. Indeed,

it is bound to happen, since

a work does not have a

single fixed form that is

valid for all time. Only if

it stands up to being

illuminated from different

sides and challenges us to

throw light on it in this

way - only then is it great.

This is true even of works

of art that cannot be

changed in performance. Even

paintings, sculptures and

buildings are viewed and

interpreted in very

different ways by different

generations. It is this that

gives them their historical

status.

Herr Harnoncourt, what is

the starting-point for

your current view of

Brahms?

The orchestra and I both

start out from the wish to

rethink each piece. Brahms’s

works are a major part of

the repertory of all the

great orchestras. Simply to

play Brahms one more time is

not enough for me and is of

no interest to rne. That is

why I have returned to the

autograph scores and to

early printed editions with

Brahms’s handwritten

corrections, all of which

speak volumes. And finally I

have looked at the old

orchestral parts belonging

to great orchestras such as

the Vienna Philharmonic and

the Berlin Philharmonic.

Here I have gone back to the

earliest orchestral material

that I can find. It is

highly instructive to see

where the string players -

under Nikisch, for example -

used to change bowstrokes

and what they wrote in their

parts depending on the

conductor's instructions.

For me, this virtually

produces an aural impression

of a symphony, and it is

here that I discover my

models. I have had some

wonderful experiences both

as an orchestral musician

and as an audience member

who has heard the most

varied interpretations, but

I would not describe these

as influences. Today's

orchestral players are

astonished to discover how

many notes used to be played

in one bowstroke -

nowadays they would use four

bowstrokes. This spinning

out of the notes, with the

bow barely moving at all,

and the rich tone that was

inevitably produced when the

same bowstroke was used for

a whole minute at a time -

this was then the be-all and

end-all of bowing technique.

I

myself was trained in this

technique and had to

practise it for at least

half an hour a day. Today’s

string players have a

completely different

training. The left hand is

what matters and the right

hand seems atrophied

compared with the string

players of sixty or eighty

years ago. With the old

bowing technique you can

produce great melodic

paragraphs that sound

fantastic but that are also

comparatively quiet. In this

way I can not only make

inferences about the

dynamics, I can also try to

learn from the earlier

maestros whom I much

adrnire.

Anyone who performs

Brahms in this way will

not, I assume, regard hirn

as a Romantic.

With Brahms, it is very

difficult to give

straightforward answers. He

had great trouble inventing

tunes, and yet, in the final

analysis, his melodies are

so wonderful that you would

think they came easily to

him. This is

self-contradictory, yet it

is also the truth. Also, you

could say that Brahms

bypasses Romanticism and

goes back to much earlier

forms. His whole approach

seems relatively unromantic.

At the same time, he is very

close to Schumann, and what

I would describe as Romantic

atmosphere is so much more

developed with Brahms than

it is, say, with his

contemporary, Bruckner, that

I am

tempted to describe both him

and his "brother", Schumann,

as arch-Romantics. I

deny that Brahms was a

Romantic and, in the sarne

breath, I

describe him as the greatest

Romantic. These are the

contradictions that one must

be happy to accept if one

wants to give an honest

answer.

The Idea of a passacaglia

is basic not only to the

last movement of the

Fourth Symphony but also,

I think, to the finale of

the Haydn Variations,

which Brahms wrote in the

summer of 1873 and which

he conducted for the first

time in Vienna in the

November of that year.

For me, it’s not a

passacaglia at all. Nowadays

we call every bass ostinato

that is repeated twenty or

thirty times a passacaglia.

But far more important is

the basic principle: as with

the sarabande, folia and

chaconne, it is a kind of

dance that owes its

existence to contact between

the Spaniards and the

Mexicans and that was

originally extremely wild in

character.

In English, “passacaglia"

means a popular tune. It

was only with Bach’s organ

passacaglias that the

element of ceremonial

solemnity first entered the

form, although not even

these pieces are as solemn

as they are often made to

seem nowadays. Fundamental

to this form is the heavy

accent on the first and

second beat. Even in those

passacaglias in which Bach

does not follow this metre,

one none the less expects it

or at least senses it in the

background. In

this respect, Brahms is

just as Baroque as his

models. In

my own view, the final

ostinato variation of his

Haydn Variations is modelled

on Purcell's great

ostinatos, in which a short

and especially striking

group of notes is extracted

from a melody or bass line

and repeated, sometimes only

in the bass, at other times

in the other voices, too.

For me, these Haydn

Variations also have

something restful about

them, they are a work in

which the listener has, as

it were, to listen between

the lines. Each of the

variations has its own

highly sophisticated, subtle

dramaturgy. People used to

believe that a variation had

to mean something and that

it had to be accorded its

place in some catalogue of

the emotions. But

it is important to work out

in advance exactly where the

high points are, where the

developments lead and where

the musical argument grows

more relaxed, so that one

does not mix up the tempi

and turn the wrong

variations into displays of

unbridled virtuosity,

instead of bringing out

these very small subtleties

and allowing the listener to

hear them. In these Haydn

Variations, there are

strettos and metrical shifts

that are so small and subtle

that one does not notice

them in most performances.

One could perhaps argue

that these Haydn

Variations also reflect

what I am tempted to call

the spirit of the age.

When Brahms first

began to take

an interest in the St

Anthony Chorale, not only

was the painter Anselm

Feuerbach treating the

subject of St Anthony's

temptations in a life-size

canvas, but Gustave

Flaubert's novel La

Tentation de Saint Antoine

was appearing in print in

Paris. But you would

presumably agree that it

is probably a little

far-fetched to see in this

set of variations a

musical illustration of

the stations in St

Anthony's life.

It may well be possible to

do so, but I

think it is of no importance

whatsoever. Music often

draws for its inspiration on

literary or pictorial

sources. The musicologist

Arnold Schering examined

this subject in great detail

and formulated everything so

apodictically that one feels

called upon to contradict

him, even though much of it

is perfectly true. But

composers are not interested

in conveying this to their

listeners. In

the case of the Pastoral

Symphony, for example,

Beethoven

was in some doubt as to how

much he should initiate the

listener into what he

thought and felt. With his

piano sonatas, too, he

argued with his publishers

and friends over whether to

reveal their sources of

inspiration and generally

refused to do so. A

performer who none the less

manages to guess what lies

behind a piece may well play

it slightly differently. But

if the programme is

explicitly included in the

score, he will try to

express it in musical terms.

I respect the composer's

desire to keep things hidden

and do not think that I

would conduct the Haydn

Variations any differently

if I knew that the piece was

about the temptations of St

Anthony. For me, these

variations are in themselves

a temptation, I don't need

St Anthony as well.

In 1880, seven years

after completing the Haydn

Variations, Brahms spent

the summer at Bad

lschl and wrote two overtures,

"one of which weeps, while

the other one laughs".

They are, of course, the

Tragic Overture and the

Academic Festival

Overture. As with the

symphonies, these

twa pieces again

constitute what Spitta

called an "imaginative

contrast".

These two overtures deserve

to be taken far more

seriously than they are. Of

course, it’s not hard to

take the Tragic Overture

seriously, but to regard the

Academic Festival Overture

as no more than a student

joke is really selling it a

bit short. It is

a magnificent work, music

with a great deal of cryptic

humour. One senses Brahms`s

friendly links with academic

circles in Vienna, certainly

also the gratitude that he

wanted to express for the

honorary doctorate awarded

him by Breslau University.

But it's clear that today's

musicians and listeners are

unfamiliar with these songs.

The Academic Festival

Overture is not simply

music. Whenever I conduct

this work, I always sing all

these songs to the orchestra

- it goes without saying

that I know them all and,

wherever possible, I sing

them in the version current

in Brahms's day. Only then

does one sense the laughter

and the tears. More than any

other piece, this overture

tells us exactly what people

laugh at. The orchestra is

actually used here to make

people laugh. And as every

clown will tell you, the

hardest thing of all is to

be genuinely funny.

Editor:

Ute Fesquet

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|