|

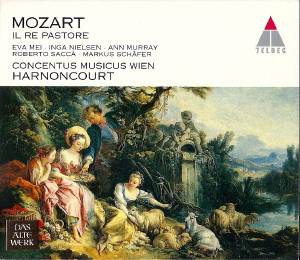

2 CD -

4509-98419-2 - (p) 1996

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Il re pastore, KV 208 |

|

|

|

| Serenata in

due atti - Libretto: Pietro Metastasio |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ATTO PRIMO |

|

53' 31" |

|

| - No. 1

Overtura |

2' 55" |

|

CD1-1 |

| - "Intendo

amico rio" - (Aminta) |

2' 32" |

|

CD1-2 |

| -

Recitativo: "Bella Elisa? idol mio?" -

(Aminta, Elisa) |

2' 17" |

|

CD1-3 |

| - No. 2

Aria: "Alla selva, al prato, al fonte" -

(Elisa) |

5' 47" |

|

CD1-4 |

| -

Recitativo: "Ecco il pastor" - (Agenore,

Alessandro, Aminta) |

1' 47" |

|

CD1-5 |

| -

Recitativo accompagnato: "Ditelo voi

pastori" - (Aminta) |

2' 27" |

|

CD1-6 |

| - No. 3

Aria: "Aer tranquillo e di sereni" -

(Aminta) |

6' 28" |

|

CD1-7 |

| -

Recitativo: "Or che dici Alessandro?" -

(Agenore, Alessandro) |

1' 13" |

|

CD1-8 |

| - No. 4

Aria: "Si spande al sole in faccia" -

(Alessandro) |

4' 46" |

|

CD1-9 |

| -

Recitativo: "Agenore? T'arresta" -

(Tamiri, Agenore) |

1' 37" |

|

CD1-10 |

| - No. 5

Aria: "Per me rispondete" - (Agenore) |

3' 27" |

|

CD1-11 |

| -

Recitativo: "No: voi non siete, o Dei" -

(Tamiri) |

0' 42" |

|

CD1-12 |

| - No. 6

Aria: "Di tante suepecorelle" - (Tamiri) |

4' 34" |

|

CD1-13 |

| -

Recitativo: "Oh lieto giorno!" - (Aminta,

Elisa) |

2' 11" |

|

CD1-14 |

| -

Recitativo: "Elisa! Aminta! E' sogno?" -

(Aminta, Elisa) |

0' 39" |

|

CD1-15 |

| -

Recitativo accompagnato: "Che? m'affretti

a lasciarti" - (Aminta, Elisa) |

3' 37" |

|

CD1-16 |

| - No. 7

Duetto: "Vanne, vanne a regnar ben mio" -

(Elisa, Aminta) |

6' 22" |

|

CD1-17 |

|

|

|

|

ATTO SECONDO

|

|

53' 58"

|

|

| -

Recitativo: "Questa del campo greco è la

tenda maggior" - (Elisa, Agenore) |

1' 36" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - No. 8

Aria: "Barbaro! oh Dio mi vedi" - (Elisa) |

6' 07" |

|

CD2-2 |

| -

Recitativo: "Nel gran cor d'Alessandro" -

(Agenore, Aminta, Alessandro) |

4' 24" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - No. 9

Aria: "Se vincendo vi rendo felici" -

(Alessandro) |

6' 27" |

|

CD2-4 |

| -

Recitativo: "Oimè! declina il sol" -

(Aminta, Agenore) |

1' 23" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - No. 10

Rondeaux: "L'amerò, sarò costante" -

(Aminta) |

7' 58" |

|

CD2-6 |

| -

Recitativo: "Uscite, alfine uscite" -

(Agenore, Elisa, Tamiri) |

2' 11" |

|

CD2-7 |

| - No. 11

Aria: "Se tu di me fai dono" - (Tamiri) |

5' 33" |

|

CD2-8 |

| -

Recitativo: "Misero cor!" - (Agenore) |

0' 24" |

|

CD2-9 |

| - No. 12

Aria: "Sol può dir come si trova" -

(Agenore) |

3' 10" |

|

CD2-10 |

| - No. 13

Aria: "Voi che fausti ognor donate" -

(Alessandro) |

4' 27" |

|

CD2-11 |

| -

Recitativo: "Olà! che più si tarda?" -

(Alessandro, Tamiri, Agenore, Elisa,

Aminta) |

3' 40" |

|

CD2-12 |

| - No. 14

Coro: "Viva, viva l'invitto duce" -

(Elisa, Tamiri, Aminta, Agenore,

Alessandro) |

6' 29" |

|

CD2-13 |

|

|

|

|

| Roberto Saccà,

Alessandro, Re di Macedonia |

|

Ann Murray, Aminta,

Pastore, amante di Elisa

|

|

| Eva Mei, Elisa,

Nobile ninfa di Fenicia, amante di

Aminta |

|

Inga Nielsen,

Tamiri, Figliola del tiranno

Stratone, amante di Agenore

|

|

| Markus Schäfer,

Agenore, Nobile di Sidone, amante

di Tamiri |

|

|

|

Continuo:

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo /

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello

|

|

| Phonetic coach:

Paola Viano |

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violine |

-

Gerold Klaus, Viola |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine |

-

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

-

Howard Penny, Violoncello |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violine |

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Violone |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violine |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

-

Robert Wolf, Flauto traverso |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Reinhard Czasch, Flauto traverso |

|

| -

Sylvia Walch-Iberer, Violine |

-

Hans-Peter Westermann, Oboe |

|

| -

Editha Fetz, Violine |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe |

|

| -

Barbara Klebel, Violine |

-

Alberto Grazzi, Fagott |

|

| -

Thomas Fheodoroff, Violine |

-

Hector McDonald, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Ursula Kortschak, Violine |

-

Elizabeth Randell, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Annelie Gahl, Violine |

-

Michele Giascarino, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter junior, Violine |

-

Sandor Endrödy, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Elisabeth Stifter, Violine |

-

Andreas Lackner, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Lynn Pascher, Viola |

-

Herbert Walser, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Dorle Sommer, Viola |

-

Michael Vladar, Pauken |

|

| -

Gertrud Weinmeister, Viola |

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Musikverein,

Vienna (Austria) - maggio 1995 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

"Das Alte Musik" - 4509-98419-2 - (2 cd)

- 53' 31" + 53' 58" - (p) 1996 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

The Themes of Il

re pastore and the Formal

Canon of opera seria

The idea

of the "re pastore" or

shepherd king can be traced back to

the biblical figure

of King David and

was long an integral part of the

western myth of

kingship. The mark of such a ruler's

legitimacy lay; in part, in the fact

that he was chosen by a superior

power, but it also stemmed from his

consciousness, as one of the elect, of

his responsibility towards the people

placed in his charge. His adversary

was traditionally a tyrant who, in his

quest for absolute control,

arrogates power to himself and

rnisuses it for his own dcspotic ends

This contrast between just and unjust

claims to power is one of the hasic

themes of opera seria, a genre

that originated in the l7th century

and which. in terms of hoth form

and content, proved particularly well

suited to portraying not only

idealised power and grandeur but

also the virtues that were believed to

distinguish a monarch above all others.

Opera seria evolved against a

courtly background and soon came to

mirror courtly existence. Just

as life at court was determined by

endless ceremony, so opera camo to be

dominated by a stereotypical

dramaturgy that prescribed the

relationships between the characters

and the sequence of musical forms. All

the features of a courtly festivity

were faithfully preserved even when

the performance took place in a public

theatre. Themes and

staging were always closely hound up

with courtly ceremony, hence,

presumably, many of the difficulties

that arise when these works are staged

today. The themes on which opera

seria drew were hased on a

pre-existing, socially inviolate

system of values that conditioned the

responses of all the characters and

determined all their actions. Plots

were generally borrowed

from classical myth and history, with

the result that the characters

acquired a significance that was not

so much individual as illustrative

and allegorical. Situations and

emotions were highly stereotyped and

thus part of a symbolic. unnersally

valid transcendental reality.

Initially; the heroic action's

rigid framework was broken

down by the introduction of comic

characters and scenes, but

this all changed following attempts

to reform the genre by poem

such as Apostolo Zeno and Pietro Metastasio,

who sought to bring it closer to

classical drama, with its insistence

on unity of action.

The number of roles was reduced and

the intrigue derived from the

conflicting interests of a first and

second couple, To these were added a primo

tenore, who was generally a

ruler invested with positive or

negative features and one or two confidenti,

subsidiary figures in whom the main

characters could confide and who

helped the action along. The earlier

range of musical forms was likewise curtailed,

with choruses and accompanied recitatives

reduced to a minimum, and duets or

longer ensembles generally sanctioned

only at the ends of acts. In essence,

the action unfolded within a fixed

framework of secco recitatnes

and arias. The recitatives carried the

action forward, whereas the arias -

mostly placed at the end of a scene -

interrupted it, while none the less

fulfilling an essential dramaturgical

function by portraying the characters'

state of mind and their inner reaction

to the foregoing course of

events.

The Libretto and

Performance History of Il

re pastore

Metastasio's

libretto for Il

re pastore caught

the spirit of the age, with its Enlightened,

Rousseauvian predilection for the

virtues of a simple life -

virtues that were inevitably

much

idealised and treated as part of a

pastoral idyll by beyng reworked in a playful Rococo

spirit. In the process, the Italian

poet picked up the tradition of

the old pastoral drama from which

opera had once developed. Against this

Arcadian background, it was not

so much the heroic and historicising

intrigue that was central to the plot

as the idea of reforming and

humanising an ossified

social order through the

virtues of the heart.

For Metastasio, the

complexities of the plot were not the

result of a clash of noble and

tyrannical forces, as was normally

the case in opera seria.

Rather, they sprang from misunderstandings

that result when two

different worlds and

ways of thinking are

brought into conflict.

Alessandro embodies the

intellectually ordered sense of

vocation typical of western man. He

sees it as his duty to restore a

legitimate order that

has been overturned, while giving no

thought to the individuality of those

affected. His plans founder

on what, for him, is the incomprehensible

world of ideas of

the Asiatic characters, for whom the

claims of the heart

are more pressing than those of any

superimposed

order. As a

result, the central character

in the drama is not

the hero Alessandro but the sensitive

shepherd Aminta, who

is, of course, none other than the

unrecognised but

legitimate heir to the

throne.

Commissioned by Maria

Theresa in 1751, the libretto was first

set by the court composer

Giuseppe Bonne, but, like all

Metastasio's libretti, it was soon taken

up throughout the rest of Europe, with

the most famous composers

of the day, including Hasse,

Gluck, Sarti, Piccinni and Galuppi,

all writing operas based upon it and

invariably altering and

adapting it to suit local conditions.

For a visit to Venice

by the Emperor Joseph II in 1769, for

example,

Galuppi revised his setting of 1762

and prepared a two-act version

in the form of a serenata, a type of

musical homage of a

kind that win hugely popular at that

time at the Viennese

court.

Mozart, too, had recourse to a

two-act version of the libretto,

in his case, one that had been devised

for a performance in Munich in 1774,

with music bv Pietro Alessandro

Guglielmi. Mozart was in Munich

superintending the première

of his La finta giardiniera,

which took place in the city on 13

January l775, when he received a

commission from his Salzburg employer,

Archbishop Hieronymus

Colloredo, to write a

serenata to celebrate a visit to

Salzburg, in the April of that year,

by the Archduke Maximilian Franz. At

the same time the Salzburg court

composer Domenico

Fischietti, was commissioned to set

another of Metastasio's texts,

Gli orti esperidi. Each work

was scored for five

vocal soloists, namely, a soprano

cstrato, two

sopranos and two tenors. Two

leading artists from the Munich

Court Opem were engaged for the

occasion: the castrato Tommaso

Consoli and the

flautist Johann Baptist Becke. The

rest of the cast was made up of

members of the Salzburg

Hofkapelle. Mozart began work on the

score at the beginning of March,

shortly after his return from Munich.

He did not stick exclusively to the

Munich libretto, but on

several occasions referred back to

Metastasio's original. He also used a

revised version of a number of other

pnssuges, revisions

that are believed to he the work of

the prince-archbishop's chaplain,

Giambattista Varesco, and that include

Aminta's aria. "Aer tranquillo",

and the final

chorus, "Viva l'invitto duce", where

the original would no doubt have been

too short to provide a suitable homage

for the visiting archduke.

We know little about the first performance

of Il re pastore, which

took place on 23 April

1775 as part of a programme of

festivities extending over three

evenings. All we can say for certain

is that Mozart used

parts of the score for other

compositions and that individual arias

were later performed in concert. In

its entirety, the work was not revived

until the 20th century, initially in a

concert performance to mark the

composer's

sesquicentenary.

Humour

and Irony in Il re pastore

One of

the most basic ingredients in Mozart's

setting of the text is his use of

irony, an irony based

on the misunderstandings brought about

by the clash between Alessandro's

obsession with political order and the

emotional nature of

the Sidonian people on whom he

attempts

to impose a state of happiness.

Alessandro is incapable of

understanding their mentality, a state

of affairs that all

too often makes

his decisions seem risible,

not least because he himself never

notices that everyone

else is dissatisfied with them.

Mozart does full

justice to this inherently comic

situation by

creating two musical

worlds for his characters

to inhabit - two worlds that

tire divided from one another by a

barrier of

incomprehension. The

Arcadian world is characterised

by music traditionally associated with

peasants and shepherds and by its

varied depiction of Nature, with the

sound of flutes, for

example, evoking a pastoral mood.

Aminta's entrance aria ("Indendo amico

rio") develops

directly out of the overture and turns

into a dialogue with the orchestra,

which answers him to the strains of

the rnurmuring brook with

which he is comrnuning. The first amusing

contrast with this

mood of tranquil contemplation comes

with Elisa's entrance: although a

descendant of King Cadmus and hence of

royal rank, she looks forward to

leading a simple life with her lover,

but this idea is exposed

as an unrealistic pastoral

idyll in her lively and charming aria,

"Alla selva, al prato",

with its accompagnato interpolations

and boorishly

rustic dance motifs in the orchestra.

Here, too, there is the potential for

misunderstanding: Aminta’s

real situation is different from

Elisa's mistaken conception

of it, but love bridges the gulf between

appearance and

reality.

The very first scene

between Alessandro and

Aminta reveals the absence of any

common ground in their attempts at

mutual understanding. Although Aminta

assures Alessandro that he has no

interest in the grandeur and pomp

associated with the world of heroes,

Alessandro sees only virtuous modesty

in that assurance.

For the present

recording, the later ("B")

version of the recitativo

accompagnato, "Ditelo voi

pastori", has been preferred to its

earlier version, in order for it to

serie as an introduction

to the aria. "Aer tranquillo":

Aminta invites the shepherds to share

in his happiness and praises the joys

of a rural

existence, the carefree freedorns of

which find apt

expression in the aria's Allegro

aperto. The minuet-like middle

section depicts the contrast of life

at court, which Aminta formally reject

in the aria’s concluding da capo.

Alessandro's recitative

reveals him as no

more than a simple

army commander wanting to impose order

on the world by first destroying it.

The shepherds' irenic

ideal is ironically contrasted with

the "hero's"

warlike outlook. With its accompanying

trumpets and timpani, Alessandro's

simile aria, "Si spande al sole in

faccia", gives the hero ample

opportunity to indulge in pompous

attitudinising. Thunder and lightning

symbolise the purging storm of war

that he intends to visit on the world.

Forte upheats on trumpets and

horns and elaborate coloratura writing

suggest a surfert of activity that

turns into complacency in the aria's

slow middle section. Meanwhile, the

orchestral writing reveals that, with

his blatant obsession with order,

Alessandro is incapable of takitrg

account of his antagonists' more

peaceful rnentality.

The second couple,

Agenore and Tamiri, are very much part

of the courtly world. Agenore is a

contradictory character, involved in

several conspiracies but

devoted to Tamiri, the

refugee daughter of the tyrant

Straton, a state of affairs made clear

in his ravishingly tender aria.

“Per me rispondete", which is cast in

the form of a minuet. Tamiri's response,

"Di tante sue procelle", describes

her resultant happiness, which fills

her with a new-found sense of

liberation after all the torments and

tribulations that she has suffered.

With the final scene of the opening

act comes a dramatic increase in

tension. Hating discovered his true

identity, Aminta

decides to embrace his destiny and in

an accompanied recitative offers

dramatic evidence of the contradictory

emotions triggered by this decision

both in himself and in Elisa. The

orchestra conjures up

their doubts and secret fears, while

Elisa herself speaks of her joy.

The final duet, “Vanne

a regnar ben mio", finds Aminta

confident and resolute, Elisa lovingly

resigned and apprehensive. The

C-section, in the form of

a gavotte, sweeps aside all vague premonitions

with its apparent ioy and faith in the

future.

In the opening recitative of Act Two,

Agenore reveals himself as a pompously

self-important, fawning courtier in

his dealings with Elisa. The scene is

presumably intended as an ironical

gloss on the sort of court ceremonial

that admits of no natural

reactions. With its numerous accompagnato

passages, Elisa's aria, "Barbaro! oh

Dio", constitutes a dramatic

character sketch, as her emotions

veer between disillusionment, anger

and despair. Naïvely

self-satisfied as ever, alessandro

now looks for a further victim for

his mania for imposing order on

others: Tamiri is to marry Aminta.

Unwittingly he plunges the second

couple into a state of turmoil. With

its carefree F major tonality, his

aria, "Se vincendo vi rendo felici",

reveals the full extent of his

error. The contrast between the

reality of the situation and

Alessandro's superficial complacency

can be regarded onsly as an expression of supreme

irony: the exalted "hero" is

revealed as a blind and

uncomprehending fool. Aminta's

aria, "L'amerò, sarò costante", is

one of Mozart's most affecting

expressions of love and, as such,

the high point of the work. Cast

in the form of a rondo, it is

scored for somewhat unusual forces

(flutes, english horns, bassoons,

horns, solo violin and muted

strings) that lend it an intimacy

and, at the same time, a very real

transparency of texture. Once

again, the world of Arcadia is not

far away. The rondo form is

especially well suited to the

subject matter, with its themes of

eternal fidelity and heartfelt

love. Already inwardly resolved to

renounce the throne, Aminta is

naturally thinking of Elisa at

this point. although the

conversation has in fact been about Tamiri.

Yet, thanks to Mozart's

incomparable ability to suggest

several different layers of

meaning at once, Tamiri, too, is

involved here, since Agenore

subconsciously transfers

Aminta's confession of love to

his own feelings for Straton's

daughter: for him, Aminta can be

referring only to Tamiri. As a

result og this ambivalence, the

aria acquires a particular aura

of secrecy and mystery.

The shepherd

Aminta places the claims of

the heart above those of the

throne, but for the courtier

Agenore, the priorities are

reversed: although he loves

Tamiri, he believes it

incumbent him to renounce her

for dynastic reasons. In her A

major aria, "Se tu di me fai

dono", she confronts him

with his inconsistent and

wealdy passive attitude,

which merely serves to

intensify his anguish at the

prospect of losing the woman

he loves. He gives vent to

his despair in a highly

dramatic and agitated aria,

"Sol può

dir", the inner

restlessness of wich is

signalled by Mozart's

imaginative writing for

the woodwinds. The

contrast between Agenore's

vehement Allegro and

Alessandro's following

bravura aria in C major,

"Voi che fausti ognor

donate" (again, of course,

with timpani and

trumpets), points up the

full extent of the

latter's blindness: he

sees only superficial

greatness and is blind to the

feelings of others, even

when he believes he is

making them happy. In

the face of harsh

reality, his attitude is

little less than

farcical. Even when

those whom

he has tried to make happy open his

eyes for him and

spurn his gifts, he refuses to change

his outlook. Unbidden,

he makes both couples rulers, since he

is incapable of

conceiving of such virtue without an

empire to rule. The obligatory scene

of homage, "Viva l'invitto duce",

demonstrates Mozart's subversive

irony in particularly striking

fashion: although the act of homage

is directed on a

superficial level at Alessandro - and

hence, of course, at the archducal

guest of honour -, the fêted

figure is really Cupid who, as love's

agent, proves the ultimate victor.

It may be

said in conclusion that although

Mozart retained the formal model of opera

seria in all its essential characteristics,

he also gives it a new significance by

dint of his use of irony and ability to

express contradictory emotions through

the ambivalence of

his musical language, therehy

investing Il re pastore with a

validity far beyond that

of the circumstances that first

produced it.

Johanna Fürstauer

Translation: Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|