|

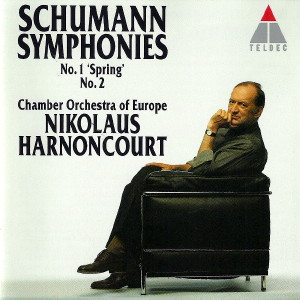

1 CD -

4509-98320-2 - (p) 1996

|

|

| Robert

Schumann (1810-1856) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 1 in B flat

major, Op. 38 "Spring" |

|

31' 24" |

|

- Andante un poco maestoso -

Allegro molto vivace

|

11' 31" |

|

1

|

| - Larghetto - attacca: |

6' 22" |

|

2

|

| - Scherzo: Molto vivace |

5' 27" |

|

3

|

| - Allegro animato e grazioso |

8' 04" |

|

4

|

| Symphony No. 2 in C major,

Op. 61 |

|

35' 38" |

|

- Sostenuto assai - Allegro,

ma non troppo

|

11' 57" |

|

5

|

| - Scherzo:

Allegro vivace |

6' 37" |

|

6

|

| - Adagio espressivo |

9' 15" |

|

7

|

| - Allegro molto vivace |

7' 49" |

|

8

|

|

|

|

|

| Chamber

Orchestra of Europe |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Stefaniensaal,

Graz (Austria) - giugno 1995 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 4509-98320-2 - (1 cd) - 67' 14" - (p)

1996 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

The

unfolding of a poetic idea

|

Listeners

expecting Nikolaus Harnoncourt

to court publicity with

headline-grabbing revelations

about Schumann as a symphonist

may well be disappointed.

Shortly before conducting the

composer's First and Second

Symphonies at the 1995

Styriarte Festival, he

confided in a journalist:

"Even now I still suffer from

the fact that each time a

player strikes his timpani

with his wooden sticks, there

are people who immediately

think that it's the result of

extensive research on my part,

whereas they take absolutely

no notice of all the things

that I've spent literally

hours working on." As with

other composers, Harnoncourt

discovered the key to

interpreting Schumann by

studying the autograph scores.

No less important a source

were letters and other

documents by the composer and

his contemporaries. But

Harnoncourt is not interested

in interpreting Schumann's

music as though it were a

series of diary entries or a

private atmospheric portrait.

His principal point of

reference remains the actual

score. "Of course, I try to

convey the contents of a piece

in such a way that it gets

under the listener's skin."

But Harnoncourt is keen not to

confuse "contents" with

"programme", even if titles

like "Spring Symphony" and

"Rhenish Symphony" - to say

nothing of Schumann's

sensitive soul - have often

misled writers into

interpreting these works from

an autobiographical standpoint

and treating them as examples

of programme music. Ronny

Dietrich observed the

conductor at work.

Even today there is

a persistent

belief that

although Schumann wrote

brilliantly for

the piano, he showed no particular

instrumentational skills in his

orchestral works. Extensive

retouchings in his scores are felt to bear this out. Nikolaus

Harnoncourt believes

exactly the opposite, arguing that

Schumann must have "thought in terms

of orchestral sonorities" right from the

outset, even in his piano pieces,

which “nearly always suggest a piano

reduction of an orchestral score".

Harnoncourt's recording of Schumann's first two symphonies

is designed to demonstrate this

thesis, inasmuch as he conducts the

scores as written, with no attempt

to conceal anything. Instead, he tewals

what, for the 19th century, were the

novel features of these works,

features that are bound

to strike 20th-century

listeners' ears with equal freshness. Schumann's

allegedly weak orchestration emerges

as part of a coherent and organic,

if unconventional, message that ts

placed in the service

of the compositional idea.

Schumann's First Symphony in B flat

major op. 38 ("Spring

Symphony") was sketched in a

matter of only four days, a period

whose brevity was not only typical

of the spontaneity of his invention

in general but almost a precondition

of the poetic idea that Schumann

demanded a work should encompass. In

contrast to what might be called the

processual nature of the

compositional technique underlying

Beethoven's

symphonies, with their long and

laborious genesis, unrfonnity of

mood was central to Schumann's

symphonic conception. Among the

features that guarantee this unity

are the thematic links between

individual movements. In the ctne of

the B flat major Symphony it is the

initial motif on horns and trumpets

whose melodic and rhythmic potential

is explored in the later movements.

Rhythmically, this

motif is based on the metre of the

final line of a poem

by one of Schumann’s contemporaries,

Adolf Böttger, "Im Tale zieht der Frühling auf" (Spring marches

into the valley), a poem that is believed to have

inspired Schumann to write the work

and to have given it

its sobriquet. And yet, its subtitle

notwithstanding, the "Spring Symphony" is anything

but an example of programme music: "I wrote the symphony

at the end of the winter of 1841

[23-26 January

1841]," Schumann informed Louis

Spohr in a letter of 23 November

1842. “It was

inspired, if I may

say so, by the spirit of spring

which seems to possess us all anew

every year irrespective of age. The

music is not intended to describe or

paint anything definite, but I believe the season

did much to shape

the particular form

it took." In

order to preempt all possible

misundeistandings,

Schumann deleted the movement

headings in the autograph score

shortly before the symphony went to

press: "Spring's Awakening / Evening

/ Merry Playmates / Mid-Spring."

Conversely, it

seems legitimate to regard spring as

synonymous with new departures, not least because, in his letter

to Spohr; Schumann refers

specifically to the significance of

the time at which the work was

written in September 1840, after

endless struggles, he had finally

surmounted the last remaining obstacle that

stood in the way of his marriage to

Clara Wieck. And whereas his

creative abilities had threatened

for a time to desert him as a result

of the ugly scenes with Clara’s

father, the new year brought with it

a new-found interest

in the symphony as a genre This

sense of a new departure is rendered

explicit in the present recording

not only by its daring directness

and often insanely encircling

figures in the symphony's outer

movements but also by a

dramaturgical approach to tempo

relationships that reflects its

cyclical structure.

Harnoncourt refuses, for example, to

allow the Larghetto

to degenerate into a Largo and, by distinguishing

between the precisely differentiated

allegro

markings, gives ample scope to

points of contemplative repose - the

symphony`s overriding sense of brio

notwithstanding.

The Second Symphony

in C major op. 61

was sketched five

years later - again within the space

of only a few days. “I wrote the symphony

in December 1845,

when I was still

ill; I feel that

people are bound to notice this when

they hear the work,” Schumann wrote

to the Hamburg

director of music, Georg Dietrich

Otten. "Only in the final movement

did I begin to feel my old self

again, but it was

only after I had

completed the whole work that I really felt any

better. Otherwise, as I say, it reminds me

of a black period. The fact that

such strains of anguish can none the

less arouse interest is clear to me

from your sympathetic comments.

Everything you say about it shows me

how well you know this music." The

"black period” to which Schumann

refers here was 1844, a time of

severe depression and panic attacks.

The composer suffered a total

physical and mental breakdown that made

composition almost impossible. Not

until 1845 did he begin to recover

and use the

time to study Bach's works in

detail. One of the fruits of this

period of intense interest in the

Thomaskantor’s music was his Second

Symphony. Both in his First Symphony and

in the preliminary version of his

Fourth Symphony in D minor of 1841,

Schumann had already found away

forward in his approach to the

symphony as a genre. Concerned as he

was to uphold existing traditions

and adapt them to his own ends, he

could now fall back

on his great

predecessors, Bach, Mozart and

Beethoven, without forfeiting his own sense

of identity, and even went so far as

to include

recognisable musical quotations: in

the third movement of the Second

Symphony (an

Adagio espressivo) we hear the

opening phrase of the Trio Sonata

from Bach's Musical Offering,

while the final movement contains a

line - “Nimm

sie hin denn,

diese Lieder” - from Beethoven's song

cycle, An die ferne Geliebte,

that had already been quoted in the

composer's Phantasie in C

maior op. 17 (with its explicit

dedication to his wife, Clara) and

in the final movement of his String

Quartet op. 41 no. 2. (In the case of the

present movement, the quotation is

heard after the development section,

with its three culminatory Generalpausen.)

Characteristic of the Second

Symphony, as it was of the First, is

the gradual unfolding of a poetic

idea first heard in the brass in the

introduction to the opening

movement. A triadic figure, it expresses what

Schumann, in a conversation recorded

by Joseph von

Wasielewski, described

as "the resistance of the spirit, a

sense of resistance which exerted a

visible influence here and through

which I sought to

counter my state of mind at that time. The first

movement is full of this sense of

struggle and is

very capricious and refractory in

character."

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|