|

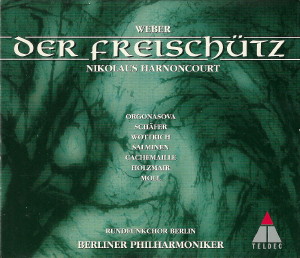

2 CD -

4509-97758-2 - (p) 1996

|

|

Carl

Maria von Weber (1786-1826)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Der

Freischütz |

|

|

|

| Romantische Oper

in drei Aufzügen - Text von Friedrich Kind

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ouvertura |

|

9' 53" |

CD1-1 |

ERSTER

AUFZUG

|

|

32' 05" |

|

| - Introduzione:

"Viktoria, Viktoria, der Meister soll

leben" - (Chor, Kilian) |

7' 41" |

|

CD1-2 |

|

Dialog: "Laß mich

zufrieden!" - (Max, Kuno, Kilian, Kaspar) |

|

|

|

| - Terzetto con

Coro: "O, diese Sonne" - (Max, Kuno,

Kaspar, Chor) |

7' 37" |

|

CD1-3 |

|

Dialog: "Komm auch in die

Schenke" - (Kilian, Max) |

|

|

|

| - Walzer ed

Aria: "Nein, nicht länger" - "Durch die

Wälder" - (Max) |

9' 26" |

|

CD1-4 |

|

Dialog: "Ich kann's nicht

verschmerzen" - (Kaspar, Max) |

|

|

|

| - Lied: "Hier im

ird'schen Jammertal" - (Kaspar, Max) |

3' 30" |

|

CD1-5 |

|

Dialog: "Elender, Agathe

hat recht" - (Max, Kaspar) |

|

|

|

| - Aria:

"Schweig, schweig, damit dich niemand

warnt" - (Kaspar) |

3' 51" |

|

CD1-6 |

ZWEITER AUFZUG

|

|

47' 01" |

|

| - Duetto:

"Schelm! Halt fest!" - (Ännchen, Agathe) |

5' 24" |

|

CD1-7 |

|

Dialog: "Es ist recht

still und einsam hier" - (Ännchen, Agathe) |

|

|

|

| - Arietta:

"Kommt ein schlanker Bursch gegangen" -

(Agathe, Ännchen) |

4' 43" |

|

CD1-8 |

|

Dialog: "Und der Bursch

nicht minder schön" - (Agathe, Ännchen) |

|

|

|

| - Scena ed Aria:

"Wie nahte mir der Schlummer" - "Leise,

leise" - (Agathe) |

10' 49" |

|

CD1-9 |

|

Dialog: "Bist du endlich

da, lieber Max" - (Agathe, Max) |

|

|

|

| - Terzetto:

"Wie? was? Entsetzen!" - (Agathe, Ännchen,

Max) |

7' 09" |

|

CD1-10 |

| - Finale: Die

Wolfsschlucht: "Milch des Mondes fiel aufs

Kraut" - (Chor, Kaspar, Samiel, Max) |

18' 52" |

|

CD2-1 |

DRITTER AUFZUG

|

|

45' 13" |

|

| - Entre-Act |

2' 41" |

|

CD2-2 |

|

Dialog: "Gut, daß wir

allein sind" - (Max, Kaspar) |

|

|

|

| - Cavatina: "Und

ob die Wolke sie verhülle" - (Agathe) |

7' 22" |

|

CD2-3 |

|

Dialog: "Max war bei

diesem schrecklichen Wetter im Walde" -

(Agathe, Ännchen) |

|

|

|

| - Romanza ed

Aria: "Einst träumte meiner sel'gen Base"

- (Ännchen) |

7' 02" |

|

CD2-4 |

|

Dialog: "Nun muß ich aber

auch geschwind" - (Ännchen) |

|

|

|

| - Volkslied:

"Horch, da kommen" - "Wir winden dir den

Jungfernkranz" - (Vier Brautjungfrau, Chor) |

4' 04" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - Jägerchor:

"Was gleicht wohl auf Erden" - (Chor) |

2' 58" |

|

CD2-6 |

|

Dialog: "Genug der

Freuden des Mahler" - (Ottokar, Agathe) |

|

|

|

| - Finale:

"Schaut, o schaut!" - (Chor, Agathe, Ännchen, Max,

Kuno, Kaspar, Ottokar, Eremit) |

20' 48" |

|

CD2-7 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang

Holzmair, Ottokar,

böhmischer Fürst / Kilian, ein

reicher Bauer |

Kurt

Moll, Ein Eremit |

|

| Gilles

Cachemaille, Kuno,

fürstlicher Erbförster |

Ekkehard

Schall, Samiel, der

schwarze Jäger |

|

| Luba

Orgonasova, Agathe, seine

Tochter |

Dorothea

Röschmann, Brautjungfern |

|

Christine

Schäfer, Ännchen, eine

junge Verwandte / Brautjungfern

|

Elisabeth

von Magnus, Brautjungfern |

|

| Matti

Salminen, Kaspar, erster

Jägerbursche |

Marcia

Bellamy, Brautjungfern |

|

| Endrik

Wottrich, Max, zweiter

Jägerbursche |

|

|

|

|

| Rundfunkchor Berlin / Robin

Gritton, Chorus Master |

|

| Berliner

Philharmoniker |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Gesamtleitung |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Philharmonie, Berlino

(Germania) - settembre 1995 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Wolfgang Mohr / Helmut Mühle /

Michael Brammann |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec - 4509-97758-2 -

(2 cd) - 70' 07" + 64' 03" - (p) 1996 -

DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Who's

afraid of the German Forest? - The sinister

undertones of Weber's Der

Freischütz

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt insights into the

autograph score and libretto recorded

and introduced by Monika Mertl

A writer of popular hits must bear the

concomitant consequences. The tunes of

Der Freischütz were soon being

whistled by barrow boys all over

Europe following the opera's hugely

successful première in Berlin on 18

June 1821, a success that led to an

ectended run of performances in the

city and that spread like wildfire

across the rest of the continent, with

stagings in Vienna, Dresden and

Hamburg within a matter of months. In

a whole series of often bizarre

adaptations, the work caught on even

in France, while at the same time

dominating a middleclass domestic

music-making in a way that has never

been equalled before or since. In a

graphic and satirical account of 1822,

Heinrich Heine describes how he felt

constantly "stifled vy violet silk" (a

reference to the Bridesmaids' Chorus),

yet not even he could gainsay the

"excellence" of Weber's score.

Such immense popularity invariably

rests upon misunderstandings. Thanks

to the pioneering work of the Weber

scholar, Friedrich Wilhelm Jähns, the

reception history of Der

Freischütz has benn charted in

detail from the 1830s onwards, and a

farrago of idées reçues it

turns out to be. Although the complex

background of what seems a simple

enough story has been thoroughly

analyzed over the years, in practice

the prevailing impression remains one

of harmlessness - a classic case of

repression, one suspects. The myth of

the German forest may long ago have

been discredited, but our secret

desire for a rural idyll and for

unspoilt Nature is greater than ever,

and gothic horror with a happy ending

continues to warm the cockles of the

heart.

Of particular relevance to anyone

wanting to gain access to the

fascinating but sinister world that

lies concealed beneath its harmonious

surface is the fact that the opera was

written in the wake of the Napoleon

Wars and was consciously located by

both Weber and his librettist,

Friedrich Kind, in a parallel post-war

period, namely, in the aftermath of

the Thirty Years War.

No flaxen-haired daredevil

The present recording was made in

September 1995 in conjunction with a

series of concert performances at the

Berlin Philharmonie. One of the points

that emerged most forcefully from

these sessions was the way in which

Max is characterized vocally. The

young tenor Endrik Wottrich is

uncharacteristically self-effacing for

a singer of his Fach, ridding

the role of its heroic pretensions and

giving it a totally different aspect

from the one that has become

associated with it over the years.

This is of central importance for

Harnoncourt's interpretation of the

work: Max is no dashing huntsman who

suddenly has a run of bad luck in the

psychologically stressful run-up to

his marriage. He is a dreamer and a

fantast - as Weber makes clear in his

score. In turn, this inevitably

affects the relationships between the

other characters.

On a personal level, Harnoncourt has

no time for the general tendency to

set store by psychology, but in this

particular case he proves, once again,

highly sympathetic in his analysis of

the characters, advancing his own

interpretation of Der Freischütz

on the strenght of his fundamental

loathing of every form of violence, be

it war or "merely" hunting. The opera,

he argues, is about outsiders in

conflict with crumbling conventions, a

conflict located in a field of tension

between an unprincipled

utilitarianism, with its instant

gratification, and a sense of higher

morality.

Harnoncourt first realized this

interpretation of his at the Zurich

Opera in 1993 in a production by the

late RuthBerghaus. That he felt

encouraged to renew his acquaintance

with the work was due, above all, to

the special sound quality of the

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra - a

quality that has to do with more than

merely the orchestra's famous brass

section. He regards the sound of this

orchestra as specifically "German"

and, hence, as ideally suited to Der

Freischütz.

The following conversation was

recorded during the series of concert

performances in Berlin.

Is Der Freischütz one of

the pieces - like Fidelio and

Mozart's operas - that you've always

wanted to conduct?

Yes, long before I first did in

Zurich, I wanted to get to grips with

it. Der Freischütz is terribly

compromised as a work - that's

something you feel especially here in

Berlin. The two numbers that are

always immediately applauded are the

Bridesmaid's Chorus and the Huntsmen's

Chorus.

Compromised in the sense of

intensely popular?

In the sense of intensely popular but

also in the sense of a longing for

pine-scented forests. For me, there's

a big difference between Weber's and

Heine's use of the word "German" and

the way that other people use it. Then

it loses all its subtlety and suggests

nothing so much as 'gemütlichkeit' and

picture-postcard kitsch. The players

understood this very well. We simply

refuse to believe that Weber wanted to

present such a caricature of the

"typical German", any more than his

librettist, Kind, did- I'm reluctant

in any case to distinguish between the

two of them, since words and music

form a single and indivisible whole in

this work.

Two basically different women - two

basically different men

How does this express iteself - in

the way the characters are depicted,

for instance?

There are the two female characters,

for example they're totally different

as individuals, Aennchen simply can't

understand Agathe's grief and

anxienties. She not only tries to

comfort her, she also makes fun of her

and may even hurt her feelings. I

think the Bridesmaids' Chorus tends in

the same direction. While we were

rehearing it, I suddenly remembered

how, on the eve of my daughter's

wedding in Upper Austria, peasant

girls from the surrounding area had

arrived outside the house and sung

exactly the same sort of serenades.

Songs of advice from one woman to

another, some of them even a little

obscene, a mixture of love and malice,

based on the principle: "you'll soon

see for yourself!"

In other words, the sort of

bitchiness that can characterize

women in their dealings with each

other.

Yes, indeed. But more important in my

own view is the electricity between

the couples. On the one hand, there is

this relationship between the women, a

relationship that's very strong, and

on the other hand there are two

assistant foresters, Max and Caspar.

Max is a huntsman who's really no such

thing. I always used to say at the

rehersals he reads Goethe all the

tima. I felt that was important on

account of the way the part is

characterized vocally. Normally tenors

who sing this part begin by striking a

heroic note: "Oh, this sun!" But the

problem is that 80% of the part is

marked piano, whereas the forte

and fortissimo passages are

really meant to suggest a sense of

drowning in the orchestral floodtide.

In order to show Max failing.

Exactly. Caspar, by contrast, is an

assistant forester who has just

returned home the war. That seems to

me to be an extremely crucial point.

In other words, we see the demobbed

soldiers and the huntsmen who remained

at home and who represent something

very traditional; and the peasants who

don't like the huntsmen - that's an

age-old antagonism. And it is very

much the peasants who score a victory

over Max here. These contrasts, and

the fact that Cuno's two assistant

foresters embody such extremes - it is

all this, taken together, that creates

such violent tension.

And what about the electricity

between the couples?

For me, the real couple is Aennchen

and Max. He may not be exactly the man

she'd like him to be, but when she

sings her aria about the dashing

youth, it's a musical portrait of Max,

as she imagines him to be. I think

this is bound to hurt Agathe's

feelings: "Aennchen is talking about

my bridegroom!" Weber casts this aria

in the form of a polonaise, a dance

that involves stamping the ground with

one's heel - the result is something

very muscular and powerful. But the

really great couple is Caspar and

Agathe. Agathe is too classy for Max.

Can you justify that musically?

I can also justify it in terms of the

text. There may here been something

between Caspar and Agathe before he

went off to fight in the war, but

after his return he must heve given

her the creeps with all his experinces

- presumably he spoke ot nothing else.

You can imagine all sorts of reasons.

They then split up and the next man to

come along was Max. But on a

subliminal level, this bond still

exists, hence, presumably, Caspar's

hatred of Max.

Fear as a decisive motive

That would certainly account for

Max's depression

Something must already have happened

to affect the relationship between Max

and Agathe. Max is constantly afraid

that Caspar's more powerful

personality might cause him to be

sidelined. Agathe is always talking

about Caspar, even when she condemns

him. In that way she turns him into a

threat. It seems to me impossible to

overlook that fact.

At the same time, it's very Freudian.

The closer the wedding gets, the more

Max is conscious of his failure, of

his weakness. He's anything but a

flaxen haired daredevil. When he says,

"At the evening I brought home a rich

catch," you don't have the feeling

that the object of his hunting

expeditions is deer and wild boar.

Agathe certainly puts a lot of

pressure on him.

Yes, she does, but very unconsciously.

With her, too, fear is a decisive

factor in motivating her behaviour.

And Max's fear continues to increase

in the course of the action. He knows

exactly what he's let himself in for:

The position of hereditary forester

means a job and a girl. "If you fail

at the trial tomorrow," says Cuno,

"you'll lose the girl and your job."

His whole existence is at stake.

His whole existence. I see it like

this: here's a man who bot has

to and wants to achieve a

state of normality and who, in order

to do so, has to act as a huntsman -

professionally. Scoring, after all,

always represents a concrete success

and at the same time is proof of one's

virility. By scoring, Max would

achieve a middle-class, well-ordered

existence. The world of hunting is one

that has had nothing to do with the

war, a world where everything is

regulated: the poacher is punished,

and the peasants have no say. But when

the opera begins, this well-ordered

world of hunting has been disrupted as

a peasant proves the better marksman,

and the huntsman has to put up with

public ridicule. The huntsmen's idyll

is under threat from two different

quarters: from the peasantry and from

the world of Caspar and Samiel.

Although Caspar would normally be part

of the world of hunting, he stands

apart from it by virtue of the fact

that he is a war victim.

A clear political component

You've said several times that war

plays an important role in the

piece.

Yes, that's because the work describes

a post-war period and was written

during a real post-war period.

Whit pieces like Fidelio

and Figaro you've repeatedly

stressed that they contain no

political agenda whatsoever. But Der

Freischütz must be interpreted as a

political piece in the sense that it

depicts a post-war period, in ither

words, a period when there are no

longer any valid, functional social

worms, where people attempt to cling

to traditional rituals, where there

is a blind faith in God and where

superstition...

The character of Ottokar is conceived

along these lines. I think that was

intended by the two authors. I don't

think you can read an unambiguous

political dimension into the work,

though it's certainly a powerful

component. That's clear from the

archaic world of hunting and also from

the world of authority to which the

huntsmen belong. It's obvious from

Ottokar's music that he's not a

powerful, authoritarian figure. He

must be a young mand and totally

inexperienced as a ruler - a man who

still has to fight to assert his

position and who keeps on cracking up.

Weber wrote in his sketchbooks in this

context: "An angry judge cannot be

just." That's very significant: he

wants to show us an unjust judge who

has to mend his ways. It's brilliantly

done.

This is where the Hermit comes in -

not as a representative of religion,

but as a kind of incorruptible

conscience. The Hermit's entrance is

tremendously powerful and suggests

great authority - not in the modern,

negative sense, but in the sense that

he exudes a particularly powerful

feeling of strength, something that

one can trust in. As a couple, I see

the Hermit and Samiel as embodying the

black and white aspects of the human

soul. Samiel's pronouncements in the

Wolf's Glen Scene are every bit as

authoritarian. Here, too,

contradiction is out of the question.

Utilitarianism versus morality

In other words, absolute authority

in its positive and negative

manifestations.

We're dealing with ideas here. You

could say that Samiel and Caspar

embody utilitarianism at its most

extreme: the arm in using magic

bullets is deferred, the price doesn't

have to be paid for three years, only

then can one see the consequences.

Against this is the authority of a

morality that negates utilitarianism.

After all. morality can't be justified

on the grounds of usefulness, but must

be motivated by some other factor. It

isn't so easy to justify morality.

As a general concept, it's very

interesting to see how these

principles of good and evil square

with characters who are incredibly

modern from a psychological point of

view.

I agree. I also find it interesting

that the piece originally began with a

scene between the Hermit and Agathe.

Weber had already started to set it to

music, when his wife, who, as a

singer, had a well-developed sense of

the theatre, said that it was silly

and that the opera should begin with

the common people. The librettist must

have been really furious, letters were

exchanged, he felt that his

views had been ignored and insisted

that the scene should at least appear

in the printed edition of the

libretto. On the one hand, it's a

brilliant idea that the Hermit is now

mentioned only in passing. On the

other hand, it would of course be

great if the Hermit's entrance were a

reappearance, since it would provide a

tremendous link between the beginning

and end of the work.

As it is, it is, of course, an

extremely effective moment on stage.

I think Weber was grateful to his wife

for her advice. The relationship

between the two of them is extremely

interesting, quite apart from all

this.

A musicall portrait of a

disrupted idyll

When you studied the autograph

score, what were your principal

discoveries?

That the autograph score contains no

mistakes! It's perhaps worth adding

here that there is a very fine

facsimile edition of it. My main

discovery was that in later editions

everything has been standardized by

analogy, even - and especially - where

Weber has drawn the most

extraordinarily subtle distinctions;

articulation and dynamic markings have

been totally unified. If one part is

marked forte or fortissimo,

this has simply been carried over into

all the other parts, too. But Weber

uses fives different dynamic markings

from pianissimo to fortissimo,

sometimes at one and the same time.

Which is surprisingly modern. A

clarinet will have a sudden crescendo,

for example, while the other

instruments remain quiet. During the

double chorus for huntsmen and

peasants, the strings play piano,

the horns fortissimo. It

barely comes off, but it's so well

done that the result is a real sense

of transparency. I've simply restored

the original dynamics. The result, in

a word, is a different tonal picture.

And it is this that conveys the

feeling of disquiet that is so

striking about your interpretation

of the score. With all these dunamuc

shifts and displaced accents, all

these syncopations, you feel that

there's something not quite right

beneath the surface.

The metrical hierarchy is constantly

undermined. But there's something else

that's important. Jähns, who was only

twelve when he attended the first

performance, later consulted many of

the musicians, including the first

Agathe. He wrote down the metronome

markings, showing how Weber took the

different tempi, and he commented on

them, comparing them with what was

normal in his own day. I found that

very interesting and have allowed it

to filter through into my own

interpretation.

In my own recollection of the

Zurich production there was one

particularly striking departure from

the usual tempi, the aria "Leise,

leise".

Of course, one has to take account of

the fact that different singers have

different lungs. But there's a sense

of total calm, total stasis here. I do

believe that that os what Weber

wanted.

You've mentioned the progressive

nature of the score...

The use of leitmotifs to hold the

piece togheter is really very

noticeable. There'd been nothing like

this previously, at least not on this

scale. The overture is almost like a

quarry, a great mine of blocklike

material from which the veins of the

music extend as far as the finale.

The overture begins with a crescendo

extending over the first two bars. It

quite clearly signifies a threat. The

answer on the violins is equally

certainly an expression of

consolation. And then you get this

passage on the horns that must

represent Nature. One mustn't be

afraid of conjuring up the German

forest here, there's nothing evil

about it. This helps to locate the

piece in a specific place: it is an

outdoor piece and at the same time a

night-piece.

But the cellos then add a sforzato

accent that has nothing to do with the

forest but which disrupts the horn

melody suggesting that there's

something not quite right about this

forest, something sinister and

oppressive: it's not just a place of

peace. It's also dark in the forest,

there's that as well. That's why it's

so quiet - in contrast to the

Huntsmen's Chorus, which is incredubly

loud and up-front.

The Samiel motif then bursts into this

world of the German forest, a motif

heard on timpani and pizzicato double

bass on the second and fourth beats of

the bar. It's clear to even the

dullest listener that this motif will

dominate the piece. And this disquiet

associated with Samiel proves the

starting-point for the Vivace, which

begins with the very motif that Max

will later sing in his aria: "But dark

forces are ensnaring me!" - although

Nature is really great! We've just

heard what these dark powers sound

like.

An ambiguous finale

What does the musical subtext have

to tell us about the character's

state of mind?

The Trio in Act Two is very

interesting in this context. It's

dominated by Agathe's feelings of

anxiety. The motif, "I'm so afraid, o

stay!", is a very Romantic figure,

except that it's normally syncopated:

this descending scale is very

striking. And this motif is taken up

again and again. Max sings the words

"Should fear dwell in a huntsman's

heart?" to it, punching out the

crotchets as though trying to pluck up

courage. Following a vigorous phrase

in the orchestra, during which Max

looks at the moon - it's brilliantly

orchestrated with the flutes, so that

the moon actually seems to shine -

Aennchen asks, "Do you want to observe

the heavens?" - very cheekily, without

any reference to the events outside.

To which Max replies, giving his voice

a totally new colour: "My word and my

duty call me from here. "At this point

the orchestra plays the motif first

heards "O stay". That is to say: "I'd

much rather stay here, since I too

feel a very reals sense of panic." And

this fear is now fortissimo,

whereas previously it was piano.

And then he sings, to the Fear motif:

"My word and my duty call me from

here." I think it's very subtly worked

in. After that it gets quieter and

quieter, and the word "Farewell" is

sung to a very inward dolce:

it's not just any farewell.

They're all afraid, even Aennchen. And

then the figure is inverted: Max has

to summon up his whole strenght before

finally tearing himself away. If Max

were portrayed as a valiant huntsman,

there'd be horn calls here: no fear

dwells in the huntsman's heart. But

the music says it all: he's scared

shitless.

Yes, I can see that. I always have

a problem with Max's aria: is it

only in his imagination that he was

once a dashing youth, or was he

really once like that?

When he explains what he used to be

like, the tenderness and lyricism of

the music contradict him. The melody

expresses an incredible sense of

happiness and delight, as though he's

floating on air. It's impossible to

imagine him in a huntsman's boots.

What he remembers I see as unreal.

Huntsmen, like anglers, are known for

their tall stories.

His memory of himself as a

hard-hitting, optimistic, fashionable

and dashing hutman is nowhere

confirmed by the music. The only hunt

that takes place is the Wild Hunt in

the Wolf's Glen Scene. If the forest

that is heard in the music at the very

start of the overture were a game

reserve, it would sound completely

different. Virtually every symphony of

the period ended with a tempo da

caccia - it was a language that all

composers spoke fluently. But Weber

describes a dark forest with a groan

of anguish on the cello. It hardly

suggests the good luck of a German

huntsman. For that, you'd need at

least to have a reminiscence of the

Huntsmen's Chorus in the overture, but

that's precisely what you don't get.

One thing is certainly

noteworthy: quite apart from the

fact that Weber's intentions are

clearly written into the score, he

also expressed his views most

emphatically in an interview with

his fellow composer, Johann

Christian Lobe, in the course of

which he explicitly stated that he

was concerned with images of the

sinister and eerie.

He said that people would be surprised

that so much takes place in the dark.

And in spite of these remarks,

which were published as long ago as

1855, people have consistently

interpreted it differently.

Even Jähns reports that the work's

performing history was tending in the

direction of greater liveliness and

gaiety. The whole of the German

gymnastics movement that arose in the

early years of the 19th century and

that stressed the importance of

physical exercise in moulding the

German national character at a time of

nationalist aspirations had a powerful

influence on Spieloper,

altough it is not clear exactly why

this should have been so. But it may

have been this mentality that allowed

numbers such as the Bridesmaids'

Chorus and the Huntsmen's Chorus to

take root in the German consciousness.

Weber could certainly write effective

numbers. I've never attended a

performance of Der Freischütz

when the audience hasn't applauded

Agathe's aria or Aennchen's two arias.

But I've never know Max's aria to be

spontaneously applauded. It ends on

such an oppressive note that there's

no sense of joyful expectation. Weber

was aware of what he was doing:

something like that doesn't happen

just by chance.

A brief word on the ending of the

piece. It ends in C major, and Weber

writes: "The whole thing ends

happily. "But is it really a happy

ending?

There's certaninly something of a

happy ending about it. At that time, a

year's delay in an engagement was like

saying: "You can get married

tomorrow." But Caspar's death

overshadows everything. The finale

seems something of an afterhought. It

includes a quotation from the

overture, which also ends in C major.

Formally, it's good that this whole

arch rests on two such solid pillars.

But I must say that I sometimes find C

major to be particularly oppressive.

The saddest funeral march that I know

is the Dead March from Handel's Saul

- and it's in C major. And then

there's the ending of Così fan

tutte: there's this sense of

upheavel; everything seems to have

sorted iteself out, and yet you feel

that it's all wrong, in spite of the C

major, or precisely because of the C

major. The same is true of Der

Freischütz. In the hierarchy of

tonalities, C major means

"everything's all right", but not in

the way that F major does. F major is

really yhe tonality of Christmas. But

in any case, things are not

all right at the end of Der

Freischütz: this remote and

isolated world is now severely

compromised. The messages is: let's be

brave! We'll go on living we'll manage

somehow, in five years' time we'll

have forgotten all about it. Like all

great pieces, it has these ambiguities

to it.

Translation: Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|