|

1 CD -

4509-94543-2 - (p) 1996

|

|

| Felix

Mendelssohn (1809-1847) |

|

|

|

| Die schöne Melusine, Op. 32 |

|

12' 16" |

|

| - Overture

|

12' 16" |

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

Franz Schubert

(1797-1828)

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 4 in C minor, D

417 "Tragic" |

|

33' 39" |

|

| - Adagio

molto - Allegro vivace |

10' 30" |

|

2

|

| - Andante |

9' 06" |

|

3

|

| - Menuetto:

Allegro vivace |

3' 10" |

|

4

|

| - Allegro |

10' 53" |

|

5

|

|

|

|

|

| Robert Schumann

(1810-1856) |

|

|

|

Symphony No. 4 in D

minor, Op. 120

|

|

30' 17" |

|

| - Ziemlich langsam -

Lebhaft |

11' 12" |

|

6

|

- Romanze: Ziemlich

langsam

|

3' 46" |

|

7

|

| - Scherzo: Lebhaft |

5' 26" |

|

8

|

| - Langsam - Lebhaft |

9' 53" |

|

9

|

|

|

|

|

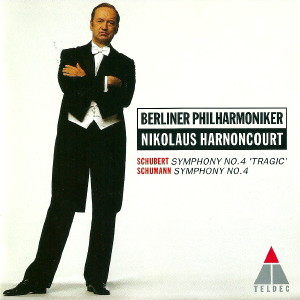

| BERLINER

PHILHARMONIKER |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Philharmonie,

Berlino (Germania) - gennaio 1995

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 4509-94543-2 - (1 cd) - 76' 34" - (p)

1996 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Franz

Schubert

"...behind the grief

lies happiness..."

"With

his Fourth Symphony," Niltolaus

Harnoncourt once observed, "Schubert

set out to open up a whole

new world in symphonic writing."

Unfortunately this verv work - to

which the composer later gave the

title "Tragic" - still suffers from

certain fixed ideas which tend,

rather, to limit its particular

significance. Iu the

l9th century, it was felt to occupv an

intermediate stage in Schubert's

development, "a transition to

something larger and greater". Among

the reasons adduced for this view were

external factors, including the

composer's first symphonic use of a

minor tonalitv, the instrumental

resources on which he calls and the

fact that he had recently given up

teaching.

Above all, howerer,

the work was said to mark the

beginning of a conscious

attempt on his part to come to terms

with Beethoven's symphonic style. Its

title and tonality ("Beethoven’s C

minor" - as though C

minor were Beethoven’s

exclusive preserve) have ensured that

Schubert's Fourth Symphony has always

been regarded as a work

which,

to quote Alfred

Einstein, reveals the extent to which

its composer was "disturlbed

by Beethoven". With this judgement

ringing in their ears, far too many

writers and listeners have

found that their minds are made up

in advance Schubert is said to hare

been unable to meet the expectations

of listeners keen to

hear "genuine Beethovenian tragedy"

and, although still only nineteen years

old, has been reproached for the fact

that his "Tragic" Symphony did not aim

to create a sense of drama in its

thematic and motivic writing, a drama

achieved by treating the entry

of the recapitulation as the climax of

the symphony's first

movement or by ensuring that the final

movement was the culmination of the

four-movement structure

as a whole. "Beethoven fought with the

spirit, Schubert merely suspected its

existence" was one of the comparative

judgements passed on the composer

"Defiance became pain, lamentation and

lyrical playfulness" was another.

Far more instructive than any attempt

to posit parallels with Beethoven is

the fact, first, that the composer's

Fourth Symphony

is a radically different work from his

Fifth, in spite of the fact that both

were written within a few months of

each other in 1816 and, second, that

during the ten months between the

completion of the Third Symphony in

July 1815 and his

work on the Fourth

in April 1816 Schubert wrote

some 190 importat songs,

to say nothing of a good two dozen

works in other genres - an oratorio, a

mass, several Singspiels, choruses,

chamber music for strings, and piano

pieces. The radically

innovative features that characterised

Schubert's lieder writing and placed

him in the avant-garde among composers

of his own day are also found in his

handling of large-scale symphonic

form, with the result that the

Fourth Symphony is anything but

traditionally hidebound. What is

emphatically new about this work is

the way in which it opens up deeper

layers of expression on a plane which,

no longer merely private, is now

necessarily universal. Within the

context of Schubert's symphonies, the

Fourth is the first example of the

composer portraying general - one

might almost say social - conflicts.

In the course of a

conversation held during one of his

rehearsals, Harnoncourt

attempted to define this qualitatively

novel aspect and to qualify

speculations on the question of the

work's title: "I know that all the

thoughts that one may have in this

respect can help us to understand a

work better. I, too, ask

myself these questions, I'm

interested in what Schubert was

reading at this time, what he heard,

what may have impressed him. In other

words, I try to see his works within

the context of his life. But when I

perform these works, this knowledge

and understanding exist only somewhere

in my unconscious. They no doubt

affect my interpretation, but not on a

conscious level. Schubert knew a lot

of what Beethoven had written, and I

know that it left a very deep

impression on him;

he knew every note of Mozart's music

that could be heard at that time, and

I know that it all affected him

profoundly, also that he suffered from

the knowledge that inferior music can

be hugely successful. I'm

absolutely certain that all

these impressions produced reactions

in his imagination." When asked about

the description of the work as

Schubert's "Tragic"

Symphony, Harnoncourt replies: "I like

things that are inscrutable,

and I harbour doubts about everything

that isn’t. When someone says, 'I've

discovered something,' I

always think that it could be

completely different."

But Harnoncourt is

sure that the idea as a whole is

intimately bound up with what is

actually expressed in this symphony,

not only in terms of its overall

structure hut also on the level of

every last detail - details which,

seemingly insignificant, are none the

less decisive: "The interlinking of

the different movements - above all

the first and last - is tremendous.

It's even taken to the point where the

movements could he interchangeable.

The solution to the problem of the

hopeless, desperate, disconsolate

situation is repeated three times

before the recapitulation in the

second part of the final movement and

explains why this broken triad on the

bassoons (which was played by only one

bassoon in Schubert's original

version, rather than by the whole bass

group, including the cellos) is now

suddenly in the major. This upswing to

the major gives the

whole of the final movement’s

development section a tremendous

sense of blissful happiness. Even

given the feeling of tragedy and

hopelessness that had previously

dominated the movement, there is now,

so to speak, a window that can be

opened on happiness - if

only for a moment.

It can't always remain

open, but it exists, And that's very

important. For me,

Schubert is always sad, even in the

Fifth Symphony, always. But in all his

grief there is also always momentary

brightness elsewhere. Wliat makes his

grief so powerful in its

impact is that behind

the grief lies happiness, lies

something bright, something sunny.

something wonderful."

Felix Mendelssohn

"...an overture that

people would receive more

inwardly..."

Mendelssohn,

too, struggled to come to terms with

Beethoven's symphonic

legacy, but in his case the battle

was fought in the field of the

concert overture, with its literary

orientation, a genre that he once

defined in a letter to Carl

Friedrich Zelter as something which,

in a sense, did not belong to

“actual, i.e., musical music".

Symphonic programme music was still

in its infancy in 1833. Berlioz had

recently written his Symphonie

fantastique, but it was not

until two decades later that Franz

Liszt coined the term "symphonic

poem". Yet, even if the basic

conditions of the new genre were not

to be formulated until much later,

Mendelssohn's concert overture to Die

schöne

Melusine fulfils at least one

of those conditions - the congruence

of form and content - in wellnigh ideal

fashion. Whereas plot-based

narratives often lack the

recapitulations that are necessary

from the point of view of musical

form, it is the reestablishment of the initial

situation that constitutes the

essential point of the Melusine story: the

nymph emerges from the watery

element to become

the mistress of her knight and the

mother of ten human children, and it

is to the water that she must return

at the end when her secret is

revealed.

The literary source even lent itself

to what, since Beethoven, had heen

the obligatory contrast hetween the

principal musical ideas and the

depiction of the conflicts derived

from them, with the musical argument

following the fairy tale's

dramaturgical structure right down

to the very last detail. From the

outset we are confronted by two

contrastive worlds, the “real world"

of the knight and of chivalry’s

ceremonial processions characterised

by energetic and impassioned motifs,

in contrast to the serpent-woman's

wondrous, fantastical world, with

the lyricism of

what Schumann termed in "demonic

wave-like figures".

The hope that love may yet reconcile

these opposites gives wav to a

feeling of hopelessness. Whereas the

themes - and characters - had

initially been presented juxtaposed and in

sequence, the motivic contrmts that

are now introduced are increasingly

dense and interactive, finally

leading to the peripeteia in the

form of the lovers' sad separation,

which is fullv motivated both

dramatically and musically. It is clear from all

this why Mendelssohn,

in a letter to his sister Fanny

should have felt the need to

distance himself from Conradin

Kreutzer's opera Melusine,

an acclaimed performance of which he

attended in 1833:

"The overture, I

mean Kreutzer's, was encored, but I

disliked it quite particularly

[...]; I then felt a

desire to write an overture that

people wouldn't

encore but would receive more

inwardly, so I took what I liked of the

subject (and that corresponds

exactly with the fairy tale)."

Robert Schumann

"...a new form for

the vast idea of this

symphony..."

“Roberts

mind", Clara Schumann noted in lier

diary on Whit Sunday 1841, "is currently much

preoccupied; he

began a new symphony

yesterday that is intended to

comprise a single movement but to

contain an Adagio and a finale.” The

D minor Symphony was completed later

that same year, a year of symphonic

experiments that also witnessed the

composition of the first version of

what was to become Schumann's A

minor Piano Concerto, to which he gave the title

“Fantasy for piano and orchestra" on

account of its irregular form. It

was for precisely this reason that,

a whole decade later, he toyed with

the idea of using the title “Symphonistic Fantasy" for a

work that he had in the meantime

revised as his Fourth Symphony and

which had been conceived from the

outset as a through-composed and unified

cycle of movements rather than as

the usual four-movement work.

The recapitulations that may be

said to invest the movements of a

traditional four-movement work with a

sense of internal stability are now

replaced by a network of reminiscences

that cut across the movements'

boundaries, while the individual

movements remain open-ended both

formally and harmonically.

In this way, the listener's awareness

of the usual recapitulations is intensified

and extends to the work as a whole:

the repeat of the introduction in the

Romanze and the twofold

reminiscence of the main ideas

of the opening movement prepare the

way for the third and tinal return of

the introduction, as though - to quote

the composer August Halm

- "the symphony were celebrating

itself".

The work was sketched with exemplary

speed in the space of a little more

than a month - the draft is dated 7

June 1841, the eve of Schumann’s 31st

birthday - but the laborious task of

instrumenting it proved unusually

time-consuming, and it was not until 9

September 1841 that the task was

finally completed, with Schumann

devoting himself to other, more urgent

work during the intervening months,

including reading the proofs of both

his First Symphony and Fantasy for

piano and orchestra and writrng the

text of what was to be his principal

cantata, Das Paradies und die Peri.

In short, the

D minor Symphony was not completed

under any real pressure, not least

because the composer was prevented

from working upon it with any real

concentration. Indeed, this may

have been one of the reasons for

Schumann's

dissatisfaction with the work's

initial version. But even the first

performance - by

Clara Schumann - failed

to satisfy him, rn spite of a

favourable press. The fact that the

evening's main event had turned out to

be Liszt's

surprise involvement in

the proceedings may additionally have

persuaded Schumann to leave the work

unpublished.

It was Johannes Brahms

who, following Schumann's death, spoke

out against the determined resistance

of the cornposer's widow and,

advancing the claims of the earlier

version, resolutely and actively saw it

into print. Described as a "first revision",

the full score was finally published in

1891, exactly fifty years after the

work's completion.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt

has always fiercely chmpioned this

initial version of the work, and the

best possible argument in

its favour is his recording of it with

the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, a

recording that sweeps aside all

reservations on the subject (Teldec

4509-90867-2). Tempi, timbre and the

detailed handling of the agogic

markings especially in the

transitional passages between the

individual phrases, sections, formal

divisions and, finally, between the

individual movements attest to the

independent merits of this initial

version, with its translucent

chamber-like-textures.

None the less, Harnoncourt has no wish

to be tied down to this early version.

With the present recording he is able

to demonstrate the inconrparable

and unique merits

of the definitive final version with

this equally personal interpretation.

In the course of our

conversation during the rehearsals, he

told me: "It was always

part of my plan to be able to place

the two versions side by side, I'd

like to stress that once again. My

inner freedom is far greater than

people give me credit for. Even at the

tirne that I

recorded the first version, I

was already interested in the second

one, and the first one still interests

me just as much as before.” This is

not simply a question of either/or, Harnoncourt

insists and draws upon an argument

which, for all its apparent

simplicity, is none

the less compelling: one can learn to

understand each version better by

studying the other one. "By knowing

what Schumann wrote in 1841, I'm

in a better position to understand

many of the decisions he

took - this again became clear during

our present rehearsals. I'm thinking,

for exarnple, of the transitions

between the movements, but also of

certain rhythms and bass passages,

such as one in the first version,

where the bass consciously enters half

a bar too late. The second version is

both more complex and more

straightforward, but at all events it

is somehow more monumental."

This is also related in

Harnoncourt's mind to the opposition

between "freshness" and "maturity"

that is generally associated with

Schumann: "Of crucial importance to

him was the initial `idea’. Later he

became the great expert who was able

to husband his

resources and to impose a new form on

the whole vast idea of this symphony;

which is really his second symphony.

This, too, has a real sense of

greatness to it."

The question as to why Brahms and

Clara Schumann were so irreconcilably

opposed to the other version is one

that llarnoncourt considers worth

asking, yet he believes that ultimately

it is of only academic interest. In

the case of Brahrns,

he suspects that the first version “may

perhaps have attracted him on account

of its freshness and colourfulness.

And then Brahms may have regarded the

second version an perhaps coming close

to his own symphonies, even if only

because of its size. Perhaps he may

even have thought of it as something

of a rival. I don't know.

You know, it's

difficult to reconstruct someone else's

thoughts. It's

wrong to be over-confident. It

could be completely different.”

Rainer

Cadenbach

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|