|

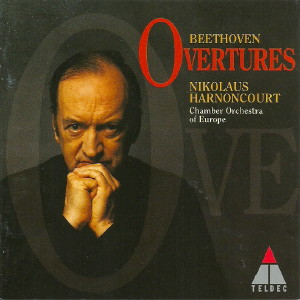

1 CD -

0630-13140-2 - (p) 1996

|

|

Ludwig van

Beethoven (1770-1827)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Overtures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Coriolano, Op. 62 - Allegro

con brio

|

8' 11" |

|

1

|

- Die Geschöpfe

des Prometheus, Op. 43 - Adagio

- Allegro molto con brio -

Introduction: Allegro non troppo

La tempesta

|

7' 16" |

|

2

|

| - Die Ruinen von Athen,

Op.113 - Andante con moto -

Allegro, ma non troppo |

5' 53" |

|

3

|

| - Fidelio, Op. 72 -

Allegro |

7' 27" |

|

4

|

- Leonore I, Op.

138 - Andante con moto -

Allegro con brio

|

10' 18" |

|

5

|

- Leonore II, Op. 72

- Adagio - Allegro

|

13' 40" |

|

6

|

- Leonore III,

Op. 72 - Adagio - Allegro

|

14' 00" |

|

7

|

| - Egmont, Op. 84

- Sostenuto, ma non troppo - Allegro |

8' 13" |

|

8

|

|

|

|

|

Chamber Orchestra

of Europe

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Direction |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

Musikverein, Vienna (Austria)

- novembre 1993 (Op. 62, Op. 43)

Concert-Hall (Megaron), Atene (Grecia) -

aprile 1996 (Op. 113, Leonore I, II)

Stefaniensaal, Graz (Austria) - giugno

1994 (Op. 72), giugno 1993 (Leonore

III), luglio 1994 (Op. 84)

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

live / studio (Fidelio, Op.

72)

|

Producer / Engineer

|

| Wolfgang Mohr / Helmut Mühle /

Michael Brammann |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec

- 4509-94560-2 - (2 cd) - 71' 11"

+ 47' 24" - (p) 1995 - DDD -

(Fidelio, Op. 72

Teldec -

0630-13140-2 - (1 cd) - 76' 06" - (p)

1996 - DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Beethoven's

Overtures represent something of a

turning-point in the history of the

genre: although written to introduce

great stageworks, they were often

divorced from that concrete context

even during their composers lifetime

and performed on their own in the

concert hall. Nowadays they are

generally heard without the following

ballet music or incidental music and,

indeed, the modern listener is often

unaware that he or she has been

deprived of the main part of the

evening's entertainment in the form of

the ballet or play. The eight

overtures featured here were intended

to introduce a variety of different

works: a ballet (The Creatures of

Prometheus), three stage plays (Coriolan,

Egmont and The Ruins of

Athens) and an opera (Fidelio),

the four overtures to which are

something of a special case in the

history of music, inasmuch as they

were written for one and the selfsame

opera. They too, however, allow us to

trace the development of the genre.

CORIOLAN

The Roman general Coriolanus is

banished from Rome in spite of all

that he has done for the city's

welfare in the course of a series

af military campaigns. Bent on

revenge, he leads an army of

Volscians against Rome. The Romans

send his mother and wife to the

enemy camp in an attempt to

persuade him ta change his mind.

Corialanus sees suicide as the

only way out of his dilemma.

The overture to Coriolan has

nothing to do with Shakespeare's Coriolanus

but was written for Heinrich Joseph

von Collin's tragedy of the same name,

which was first performed in Vienna on

24 November 1802 with incidental music

cobbled together from Mozart's Idomeneo

by Maximilian Stadler. Beethoven

himself is known to have attended this

performance. Five years later he wrote

a new overture for the play, although

in the event the piece received its

first performance not in the theatre

but at a subscription concert that

also included his first four

symphonies, his Fourth Piano Concerto

and some arias from Leonore (as Fidelio

was still called at this time). The

overture was conceived as a kind of

dramatic poem, encouraging listeners

to hear in the stark chords of the

slow introduction a musical portrait

of the hero. It freely adapts the

principles of sonata form to the

expression of human emotions, with a

gloomily agitated first subject

contrasted with a more amiably

consoling second subject.

THE CREATURES OF PROMETHEUS

The two s[tatues] move slowly

across the stage from the

background. - P[rometheus]

gradually regains consciousness,

looks towards the field, and is

pleased when he sees that his plan

is such a success; he is

inexpressibly delighted, stands up

and beckons to the children to

stop - They turn slowly towards

him in an emotionless manner. - P

continues to address them,

expresses his divine and fatherly

love for them, and commands them

(gives them a sign) to approach

him. - They look at him in an

emotionless manner - turn to a

tree, the great size of which they

contemplate. - P begins once more

to be disheartened, is fearful,

and is saddened. He goes towards

them, takes their hands and leads

them to the front of the stage; he

explains to them that they are his

work, that they belong to him,

that they must be thankful ta him,

kisses and caresses them. -

Howeven, still in an emotionless

manner, they sometimes merely

shake their heads, are completely

indifferent, and stand there,

groping in all directions.

Beethoven's holograph copy of

choreographical notes from the

scenario for No. 1 contained in the

Berlin "Landsberg 7" sketchbook.

Written in close collaboration with

the choreographer Salvatore Viganò,

the ballet music for The Creatures

of Prometheus dates from 1800/01

and received its first performance at

the Vienna Hofburgtheater on 23 March

1801. In his desire to forge close

links between plot, dance and music,

Beethoven created what for the time

was a particularly modern form of

musical dance theatre, thereby

illustrating the sort of Gesamtkunstwerk

or synthesis of the arts that was then

being discussed by Schiller and

Goethe.

These years also witnessed a revival

of interest in Greek antiquity, with

its humanistic and democratic ideals,

ideals that were often associated with

modern ideas, albeit not in any

strictly historical way, still less

from the hermeneutical standpoint

adopted by Hegel. In consequence, we

find both Goethe and Schiller

reworking the Prometheus legend - the

former in his poem of 1774 ("Here I

sit, forming men / In my own image, /

A race that shall be like me, / That

shall suffer and weep, / Enjoy and

rejoice, / And

pay you no heed, / Like me"), the

latter in his early tragedy, Die

Räuber, in which Karl Moor

laments: "Prometheus, that lofty spark

of light, has new burnt out, instead

of which we're taken in by stage

effects produced by vegetable

brimstone."

The ideas behind Beethoven’s Prometheus

are admirably summed up in a review of

the first performance: "Prometheus

banishes the state of ignorance,

civilising men through science and art

and inculcating a sense of morality.

This, in a word, is the subject

matter." The ballet's plot may be

interpreted as an allegory of the

importance of art and science in

educating and civilising mankind and,

hence, as a profound personal

statement on the composer's part: it

is art that makes us human. The

subject matter continued to preoccupy

Beethoven and he reused material from

the ballet not only in his Piano

Variations op. 35 but also in his

Third Symphony ("Eroica").

THE RUINS OF ATHENS

Prompted by envy, Minerva

refuses to defend Socrates against

his judges and, as a result, is

put to sleep by Zeus for two

thousand years. The play begins as

her period of punishment comes to

an end and a chorus of Invisible

Spirits rouses her from sleep.

Mercury takes her back to Athens,

where she is aghast to see her

beloved city in ruins and ruled by

the Turks. Rome too, she is told,

has sunk into burbarisrn. Mercury

informs her that the Muses have

fled to Pest, whither both now set

off in order to attend humanity’s

celebrations in honour of the

Muses and gods. Pest is hailed as

a latterday Athens.

The overture The Ruins of Athens

was Written in 1811/12 for a

production of August von Kotzebue's

stage play of the same name that

opened the new Hungarian Theatre in

Pest on 10 February 1812. Beethoven

himself described the rarely performed

overture as a "little work that can be

performed [...] as a refreshment". The

complete incidental music, with its

pseudo-Turkish exoticism, comprises a

chorus of Invisible Spirits, a duet

for Minerva and Mercury, a chorus of

Dervishes notable for its graphic

tone-painting, a Marcia alla Turca, a

speech for a Venerable Old Man in Pest

and, finally, a Solemn March.

Beethoven seems to have felt a certain

attachment to this music, since he

included the sixth, seventh and eighth

numbers in the programme of his

benefit concert in Vienna on 2 January

1814 (the programme also included his

Wellingtons Sieg), insisting

that the curtain should rise at a

particular moment to reveal a portrait

of the emperor - an example of his

desire that his message be put across

with the greatest possible clarity.

FIDELIO AND LEONOREN I - III

The Spanish nobleman Don

Flarestan has been imprisoned by

his enemy, Don Pizarro.

Flarestan’s wife, Leonore,

disguises herself as a man and,

under the name of Fidelio,

persuades the gaoler, Rocco, to

employ her as his assistant.

Believing Leonore to be a man,

Rocco’s daughter, Marzelline,

falls in love with her, and

Rocco's himself encourages the

match. Only her bridegroom,

Jaquino, is dismayed. Fidelio

gains Rocco’s trust and is allowed

to see the prisoner. Pizarro

arrives, resolved to murder

Florestan, but Fidelio and the

Minister’s arrival prevent him

from carrying out the deed, and

the prisoners are all set free.

Beethoven wrote no fewer than four

overtures for Leonore or (to

give it its more familiar name) Fidelio,

thus ensuring that his only opera

occupies a unique position among the

world's great classics. This embarras

de richesses is due, in part, to

the opera's complex genesis but is

also the result of purely musical

considerations. The first version of

the opera dates from 1805 and received

its first performance at the Theater

an der Wien at a time when Vienna was

overrun by Napoleonic troops. Half the

local population had fled before the

advancing French armies, and those who

remained scarcely dared venture out to

the theatre, with the result that the

opera played to a half-empty house

consisting largely of French officers

and proved a failure. This Ur-Leonore

had to be satisfied with only

three performances - performances, be

it added, that also suffered from the

censor's red pencil. A second

production opened on 29 March 1806 but

again had to be withdrawn, this time

after only two performances, since

Beethoven was unhappy with his fee.

The definitive version of the opera -

now called Fidelio - was

finally unveiled on 23 May 1814 and

this time encountered an enthusiastic

response, in part, perhaps, because

Viennese audiences now saw a link

between the opera's plot and their own

deliverance from Napoleon's tyranny.

There are four different overtures to

go with these three different versions

of the opera. The Leonore

Overture no. 1 (as it is conveniently

called) was rejected by Beethoven

following a private run-through at the

home of Prince Lichnowsky and was

heard at none of the performances

mentioned above. It did not appear in

print until 1838, eleven years after

Beethoven's death. The Leonore

Overture no. 2 of 1805 is a

substantially longer and more

autonomous piece. As such, it is

ill-suited to introducing the opera

and is best seen as a forerunner of

the concert overture. It remains

unclear which of these two overtures

was written first. The Leonore

Overture no. 3 was written for the

1806 revival of the opera. A revision

of no. 2, it is often heard today in

the concert hall, The Fidelio

Overture of 1814, finally, does not

attempt to preempt the drama but leads

neatly into it. Moreover, Beethoven’s

decision to start the opera with the

duet for Jaquino and Marzelline

altered the existing tonal

relationships and necessitated a new

overture: since the duet begins in A

major, the overture had to close on

the dominant, E major, rather than on

the C major of the three existing

overtures. All four overtures were

heard for the first time in 1840 at a

Leipzig Gewandhaus concert conducted

by Felix Mendelssohn.

In the autumn of 1809 Austria signed a

peace treaty with Napoleon and shortly

afterwards Beethoven, responding to a

commission from the Vienna

Burgtheater, began work on the

incidental music for a new production

of Goethe’s Egmont. The

overture is often performed as an

independent piece in the concert hall,

although it really needs to be heard

within the context of the incidental

music as a whole, which comprises nine

numbers in addition to the overture,

namely, four instrumental interludes,

two songs for Klärchen, a Larghetto

depicting her death, a melodrama

accompanying Egmont's thoughts on the

eve of his execution and a final

Symphony of Victory. Written some

twenty years earlier, Goethe's

five-act tragedy is set in the

Netherlands at the time of the Spanish

occupation, evoking evident parallels

with Vienna and Napoleon’s occupying

troops.

EGMONT

The hopes of all his people in

their struggle for freedom rest on

Count Egmont's shoulders, but he

is arrested by the Spanish and

condemned to death. Klärchen, a

young burgher woman, loves him and

tries in vain to incite the people

to rescue him. In the face of

failure, she poisons herself. The

imprisoned Egmont has a vision of

freedom before finally being led

away to be executed. He dies

proclaiming the words: "Protect

your property! And to preserve

your dearest ones, willingly,

gladly fall as my example shows

you. ”

The overture begins with a slow

introduction in F minor in which

gloomy chords on the strings are

contrasted with a lyrical theme on the

woodwinds. The Allegro is in Classical

sonata form, a sudden silence in the

entire orchestra following the

recapitulation. "Egmont's death could

be indicated by a rest," Beethoven

noted in his sketches. The piece

concludes with a Coda, the victorious

fanfares of which look forward to the

Symphony of Victory at the end of the

play. It was not until July 1812, two

years after he had completed the music

for Egmont, that Beethoven was

first introduced to Goethe. The

meeting proved something of a

disappointment for both men, their

respect for each other's art stopping

short of personal empathy. While

Goethe was disturbed by Beethoven’s

"unruly personality", Beethoven later

wrote: "Goethe is too fond of court

air, more than is fitting for a poet."

Andreas

Richter

Translation: Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|