|

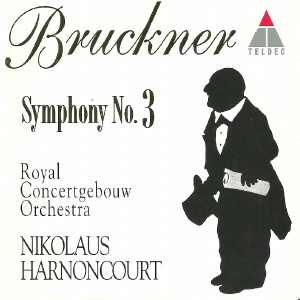

1 CD -

4509-98405-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

| Anton

Bruckner (1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 3 in D minor

"Wagner" |

|

54' 35" |

|

Version 1877, Leopold Nowak

Edition

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - I. Gemäßigt, mehr bewegt,

misterioso |

19' 29" |

|

1

|

| - II. Andante: Bewegt,

feierlich, quasi Adagio |

13' 26" |

|

2

|

| - III. Scherzo: Ziemlich schnell |

7' 02" |

|

3

|

| - IV. Finale: Allegro |

14' 37" |

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

| Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra |

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Het

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam (Olanda) -

dicembre 1994 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 4509-98405-2 - (1 cd) - 54' 35" - (p)

1995 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

"Anton

Bruckner: an antenna pointing

into 20th century"

|

Nikolaus Harnoncourt in

conversation with Walter Dobner

According to one 19th-century

revieuw of the Third Symphony,

"Bruckner has his moments -

flashes of imagination of a kind

found only with great men of

genius - but they are soon

past". I don't suppose you share

this view, Herr Harnoncourt?

Not for a moment. But nor do I

share the view of contemporary

critics of Beethoven’s Second

Symphony. None the less. there's

some truth in the suggestion that

a transcendent genius like

Bruckner - or

any other great composer for that

matter - positively invites

disapproval and criticism. You

can’t expect people to agree

completely with such music. The

whole meaning of a work is

revealed only by

contradiction. It’s only when you

ask what happens between

these flashes of genius that you

may find a lot happening that may

not appear so brilliant after all.

There was a

time when I myself saw Bruckner in

this light. I felt I was returning

home from a Bruckner

symphony with a relatively small

number of very important

discoveries. But the symphonies

were too great for that. Today I've changed my

mind completely. since I now

understand much better what this

music is all about.

Can you say in a few words what

you mean by that?

The experience I had with Bruckner

was similar to the one I had with

Beethoven. I initially had great

problems with the finale of both

the Ninth Symphony and Fidelio.

They struck me as too distended

and, in

consequence, an

seriously lacking in substance.

Only later did it become clear to

me that I was approaching this

music with the wrong standard. In

the case of the Missa solemnis

I suddenly saw that it was simply

absurd to judge Beethoven by

Mozart's standards. Beethoven

makes other demands, asks other

questions and so he got other

answers. As soon as I set aside my

"Mozart"

yardstick and found one that

seemed to me better suited to

Beethoven, I suddenly discovered a

whole new approach to his works.

Exactly the same thing happened

with Bruckner.

The more I got to know Brahms, the

more precious Bruckner became. It

was presumably

the great effort and seriousness

of Brahms's

writing that produced such

wonderful results after years of

polishing and honing and that led

me to his antithetical opposite,

Bruckner, bringing

him closer and closer to me.

Is

Bruckner not also so

difficult to understand

because there are so many

different links? Although

his music speaks the

language of the 19th

century, it is also deeply

indebted on a formal level

to the Classical 18th

century, to say nothing of

the gestures - and mysticism

- of the Middle Ages.

Curiously enough,

Bruckner strikes me - far more than

any other composer of his

generation - as someone with an

antenna pointing into the 20th

century.

When people claim that it was

Mahler who laid the foundations

of the Second Viennese School. I

have to say that this seems to

me to have

been even more true of Bruckner

- not that I would want to

disagree vdth any of the

criteria you've listed. Those

aspects that go back to the

Middle Ages are presumably tied

up in some way with Bruckner’s

markedly rustic character. But I

dont think its possible to

approach his works from a

biographical standpoint. If you

were to start out from

Bruckner's personality, you’d

expect to find extreme

conservatism in his works. But

his visions really can’t be squared with

his simplicity as a person. In

this respect he is unique as a

genius.

But is it

really possible to draw a

total distinction between

Bruckner as a person and

Bruckner as a composer?

Shouldn't the thematic

triality of his symphonic

movements be seen not only

as a symbol of the Trinity

but also as evidence of

Bruckner's personal faith?

What are your thoughts on

this and on the theory that

only a believer can

interpret Bruckner?

I don't think faith comes

into it. Anyone who performs

Bruckner needs to be familiar

with Austrian music, with

Schubert, with peasant music and

the whole ländler

thing. I wouldn't dare try to

find evidence of Brukner’s religious

beliefs in the symbols of his

music.

It may well be that these signs

of personal belief do exist, but

biographers,

exegetes and musicologists who

explain this only on the basis

of the works, without

the composer's say-so, are

guilty, I believe, of venturing

into a highly dangerous and

highly speculative area. For me,

Bruckner's symphonies are

couched in a language of musical

sounds that is his very own,

personal language. That his

personality was very strongly

influenced by his faith is

sufficiently well attested.

Whether his music would sound

different without this

pronounced religious influence,

I dont think any of us can say.

But I think it's far too simple

as an explanation to derive this

thematic

triality from the Trinity.

The "musician

of God" is only one of many

Brucknerian clichés.

Bruckner is also sometimes

regarded as a typically

Austrian composer. It's

argued that he takes his

place in a line beginning

with Schubert and leading

to Mahler and, finally, to

Schoenberg.

I'd describe only

highly concrete details of his

music as typically Austrian:

for example, the Trios in his

Scherzos and a few melodic

idem that I

associate with Bruckner's

rustic origins or with

elements of Austrian folk

music. With Schubert, it`s

totally different - he could

only be Austrian, his music

speaks Viennese dialect. The

line of development that

starts out with Schubert

certainly leads in Bruckner's general

direction. but it actuallv

goes, rather, to Johann

Strauss; that's

pure unadulterated

Austrian music for you.

There seems to me a very clear

line of

development from Bruckner

to the Second Viennese School,

especially to Alban Berg,

rather less so to Schoenberg,

although Schoenberg often

transcribed Strauss. I'm

happy to leave out Mahler - he's

really not conceivable without

Bruckner. I

regard Bruckner’s music as

absolute. The autobiographical

element in his music isn't all

that marked. Unlike Mahler, who

uses Bruckner's vocabulary,

Bruckner does not retell his

own life in a superficial way.

I see a basic difference

between a composer who sees

himself an the agent of his

talent and one who uses the

vocabulary of a composer like

Bruckner in order to tell us

all about his private

sufferings.

Herr Harnoncourt, you say

that Mahler is

inconceivable without

Bruckner. Is Bruckner

conceivable without

Wagner?

Certainly, The links between

Bruckner and Wagner must have

been in the air at the time.

You can already hear Wagner

and Tchaikovsky in a number of

Mendelssohn's works - I'm

thinking of Die erste

Walpurgisnacht and Die

schöne

Melusine. Virtually

the whole of the 19th century

is contained in these works.

One has the feeling that if

Mendelssohn had had a normal

lifespan, Wagner would have

been inhibited by such

proximity. I

don't

think there is anything in Wagner’s

musical language that wasn't already'

part of the spirit of the

times. Wagner had to exist in

the l9th century, Bruclsner

had to exist as a writer of symphonies,

not as a music dramatist.

The fact that Bruckner revered

Wagner I

see as a sign of his modesty.

Herr Harnoncourt, you're

beginning your exploration

of the world of Bruckner's

symphonies with his Third

Symphony, of which there are

three different versions.

Why did you pft for the

second version?

The final version

was ruled out for me on

account of its excessive cuts

and excisions that almost

destroy the work’s organic

unity. For me, it’s a

makeshift solution designed to

keep the symphony in the

running, as it were. The first

version is very complex and

rambling, with a lot of

Wagnerian quotations. I could

well imagine conducting this

first version after extensive

preparation. I see

the second version as the

result of Bruckner's wrestling

with the first one. Also, I think

that the coda to the Scherzo

provides a very

interesting and convincing

ending here. I think

Bruckner knew perfectly well

how he imagined his works

would sound and that he set

this down quite

clearly. He said, "My work

is in the score." But although

he worked on the score, he did

not - so to speak - prepare it

in bite-sized rnorsels. The

versions that various friends

and conductors forced out of

him were concessions to these

friends and to audiences,

prompted bv the wrsh to be

performed at all.

And which edition of this

symphony did you decide to

use for your own

performance?

I'm

conducting thc second

version in Nowak’s edition,

since it's the one I find

most convincing. You must

never forget that fashion

plays an important part here,

too. Now that we’re familiar

with Nowak's versions, we know

how he arrived at his

findings. The sources are

arailable. Of course, one

could now try reaching one's

own conclusions and results on

the strength of the sources. That's

the prerogative of eyerv

generation. I

trusted Nowak more than I

normally trust editors and

haven’t reexarnined every

question on the basis of the

sources in order to make my

own decisions, but compared

the various findings of the

individual editions. I also

consulted an edition from the

Concertgebouw Orchestra, with

whom I made this recording,

since I also wanted to learn

more about this orchestras

tradition.

Not

only the Royal Amsterdam

Concertgebouw Orchestra

can look back on a long

tradition of performing

Bruckner, so, too, can the

Vienna Symphony Orchestra,

with whom you began your

career as a musician.

They, too, have

considerable experience of

playing Brucjner's works.

To what extent was this

knowledge of the

performing tradition of

use to you during your

present involvement with

Bruckner, or did you feel

inhibited by it?

These experiences were

of great use to me and

certainly didn't

inhibit me. The older I get,

the more natural Bruckner's

musical language seems to

me. I feel at home here, it's

the element in

which I

live and breathe. I can recall

some very great performances

of Bruckner while I was a

cellist with the Vienna

Symphony Orchestra: I'm thinking in

particular of Karaian during

the 1950s. I'd

be interested

to hear those

performances again and would

like to know whether my

experience at that time -

I'd not

yet

turned thirty - would stand up

to my

present understanding. But

they left an indelible

impression on me. In the case of

the present performance it was

important for me to work with an

orchestra that knows and

understands Bruckner's language.

At the same time, of course, I

had to fight against this

experience at rehearsals,

since there are certain passages

that are interpreted in

identical ways by virtually

every conductor. I'm thinking,

for example, of the decelerandos,

especially in the slow movement

of the Third Symphony: the

answers in the orchestra are

almost always taken twice as

slowly as the questions. There

isn't the

slightest indication in the

score that this is how these

passages should be taken. And

yet orchestras are used to

playing them like this. But when

a composer like Bruckner writes

even the tiniest change of tempo

into the score and when he

prescribes even the least

expressive nuance by means of

footnotes and explanations, I'm tempted to

agree with him and inclined to

clear away all this ballast.

Translation:

Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|