|

2 CD -

4509-97684-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

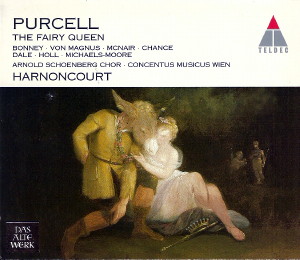

Henry Purcell

(1659-1695)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Fairy Queen, Z 629 |

|

|

|

| Libretto after William

Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's

Dream |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prelude

- Hornpipe

|

|

2' 41" |

CD1-1 |

Air -

Rondeau

|

|

2' 11" |

CD1-2 |

ACT ONE

|

|

10' 03" |

|

| - Overture |

1' 27" |

|

CD1-3 |

| - Duet: "Come, let us leave the

town" - (Bonney, Michaels-Moore) |

1' 14" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - Scene of the Drunken Poet -

(McNair First Fairy, von Magnus Second

Fairy, Holl Drunken Poet,

ASC) |

6' 07" |

|

CD1-5 |

| - First Act Tune: Jig |

1' 15" |

|

CD1-6 |

ACT TWO

|

|

23' 15" |

|

| - Song: "Come all ye songsters

of the sky" - (Dale) |

2' 14" |

|

CD1-7 |

| - Trio: "May the God of Wit

inspire" - (Change, Dale, Michaels-Moore) |

2' 48" |

|

CD1-8 |

| - Chorus: "Now join your

warbling voices all" - (ASC) |

0' 37" |

|

CD1-9 |

| - Song-Chorus: "Sing while we

trip it" - (Bonney, ASC) |

3' 54" |

|

CD1-10 |

| - Dance of Fairies - Song: "See,

even Night herself is here" - (McNair Night) |

11' 34" |

|

|

CD1-11 |

| - Dance of Fairies - Song: "I am

come to lock all fast" - (von Magnus Mystery) |

|

|

| - Dance of Fairies - Song: "One

charming night" - (Change Secrecy) |

|

|

| - Dance of Fairies -

Song-Chorus: "Hush, no more" -

(Michaels-Moore Sleep, ASC) |

|

|

| - Second Act Tune: Air |

2' 08" |

|

CD1-12 |

ACHT

THREE

|

|

20' 39" |

|

| - Song-Chorus: "If love's a

sweet passion" - (Bonney Dryad,

ASC) |

1' 55" |

|

CD1-13 |

| - Symphony while the swans come

forward |

0' 56" |

|

CD1-14 |

| - Dance for the Fairies |

1' 24" |

|

CD1-15 |

| - Dance for the Green Men |

1' 17" |

|

CD1-16 |

| - Song: "Ye gentle spirits of

the air" - (McNair) |

4' 47" |

|

CD1-17 |

| - Dialog between Coridon and

Mopsa: "Now the maids and the men" - (Holl

Coridon, Change Mopsa) |

4' 39" |

|

|

CD1-18 |

| - Dance for the Haymakers |

|

|

| - Song: "When I have often

heard" - (Bonney Nymph) |

2' 10" |

|

CD1-19 |

| - Song-Chorus: "A thousand,

thousand ways" - (Change, ASC) |

2' 32" |

|

CD1-20 |

| - Third act Tune: Hornpipe |

0' 59" |

|

CD1-21 |

ACT

FOUR

|

|

23' 38" |

|

| - Symphony |

6' 05" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Solo-Chorus: "Now the night is

chased away" - (McNair Attendant,

ASC) |

2' 09" |

|

CD2-2 |

| - Duet: "Let the fifes and the

clarions" - (Change, Dale) |

1' 15" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - Entry of Phoebus - Song: "When

a cruel long winter" - (Dale Phoebus) |

3' 33" |

|

CD2-4 |

| - Chorus: "Hail! Great parent of

us all" - (ASC) |

10' 36" |

|

|

CD2-5 |

| - Song: "Thus the ever grateful

Spring" - (Bonney Spring) |

|

|

| - Song: "Here's the Summer,

sprightly gay" - (Chance Summer) |

|

|

| - Song: "See, see my many

coloured fields" - (Dale Autumn) |

|

|

| - Song: "Next, Winter comes

slowly" - (Michaels-Moore Winter) |

|

|

| - Chorus: "Hail! Great parent of

us all" - (ASC) |

|

|

ACT

FIVE

|

|

36' 16" |

|

| - Prelude-Epithalamium: "Thrice

happy lovers" - (von Magnus Juno) |

3' 46" |

|

CD2-6 |

| - The Plaint: "O let me ever,

ever weep" - (McNair) |

7' 45" |

|

CD2-7 |

| - Entry Dance-Symphony |

9' 28" |

|

|

CD2-8 |

| - Song: "Thus the gloomy worl" -

(Chanve Chinese Man) |

|

|

| - Song-Chorus: "Thus happy and

free" - (Bonney Chinese Woman, ASC) |

|

|

| - Song: "Yes, Daphne" - (Chanve

Chinese Man) |

|

|

| - Monkes' Dance |

0' 49" |

|

CD2-9 |

| - Song: "Hark! How all things" -

(von Magnus First Woman) |

4' 28" |

|

|

CD2-10 |

| - Song: "Hark! The echoing air"

- (Bonney Second Woman, ASC) |

|

|

| - Soli and Chorus: "Sure the

dull God of Marriage" - (Bonney First

Woman, von Magnus Second Woman,

ASC) |

5' 21" |

|

|

CD2-11 |

| - Prelude |

|

|

| - Solo: "Se, I obey" - (Holl Hymen) |

|

|

| - Duet: "Turn then thine eyes" -

(Bonney First Woman, von Magnus Second

Woman) |

|

|

| - Solo: "My torch indeed" -

(Holl Hymen) |

|

|

| - Chaconne |

5' 21" |

|

CD2-12 |

| - Trio-Chorus: "They shall be as

happy as they're fair" - (Bonney First

Woman, von Magnus Second Woman,

Holl Hymen, ASC) |

5' 21" |

|

CD2-13 |

|

|

|

|

| Barbara

Bonney, Soprano |

Laurence

Dale, Tenor |

|

Elisabeth

von Magnus, Soprano

|

Robert

Holl, Bass |

|

| Sylvia

McNair, Soprano |

Anthony

Michaels-Moore, Bass |

|

| Michael

Chance, Countertenor |

|

|

|

|

| Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

master |

|

|

|

| Concentus Musicus

Wien (mit

Originalinstrumenten) |

|

-

Erich Höbarth, Violine

|

-

Gerold Klaus, Viola |

|

-

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine,

Diskantgambe

|

-

Dorle Sommer, Viola |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

-

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violine |

-

Max Engel, Violoncello |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violine |

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Violone |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

-

Marie Wolf, Blockflöte, Oboe |

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine |

-

Hans Peter Westermann, Blockflöte, Oboe |

|

| -

Irene Troi, Violine |

-

Milan Turković, Fagott |

|

-

Maria Kubizek, Violine

|

-

Andreas Lackner, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Sylvia Walch-Iberer, Violine |

-

Herbert Walser, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Thomas Fheodoroff, Violine |

-

Dieter Seiler, Pauken |

|

| -

Johannes Flieder, Viola |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Cembalo |

|

| -

Lynn Pascher, Viola |

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Gesamtleitung |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Musikverein, Vienna (Austria)

- dicembre 1994 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

Wolfgang Mohr / Helmut Mühle /

Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec "Das Alte Werk" -

4509-97684-2 - (2 cd) - 59' 14" + 60'

10" - (p) 1995 - DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

The

Fairy Queen

|

Background

Despite

an all-too-short career.

Henry Purcell (1659-95)

wrote memorable music for

the church, court, domestic

music market and for the

stage. His stage music has

received ample attention

from scholars and performers

in recent years, and

deservedly so, for it is

part of a colourful period

in Errgland's history. The

deprivations of the

Commonwealth, during which

stage performances were

severely restricted, led to

a burst of theatrical

activity following Charles

II`s ascendancy to the

throne in 1660. Restoration

audiences appeared to have

had an insatiable appetite

for music and dance, for

most plays of the period

include numerous incidental

songs and instrumental

pieces, many of which were

cleverly incorporated into

the dramatic framework.

Although Purcell wrote music

for no fewer than 42 plays,

he is best remembered for

his fire larger stage works.

The first of these, Dido

and Aeneas, the only

all-sung opera which Purcell

wrote, was performed at

Josias Priest's girls'

school in Chelsea in 1689;

this may have been preceded

by a performance at court

earlier in the decade.

Purcell's other stage works

fall into that peculiarly

English category of semi- or

dramatic operas, which can

best be described as

spectacular plays with a

substantial amount of music

and dance. They featured a

two-tiered cast in which the

principal actors did not

sing, but were instead

frequently serenaded by

minor characters and troupes

of additional dancers and

singers in fanciful garb and

guise. These works should

not be seen as imperfect or

flawed operas, for they were

not regarded an such:

Purcell's contemporaries

relished the mix of spoken

and sung drama, and did not

take to all-sung opera in a

big way until the arrival of

Handel in London nearly

twenty years after The

Fairy Queen's premiere

in 1692.

The The Fairy Queen

was first performed at the

Queen's Theatre, Dorset

Garden on 2 May 1692.

Although the total number of

performances is not known,

contemporaneous writings

suggest that it was highly

popular. The work was

revived at Dorset Garden

Theatre on 16 February 1693

with a few additional

musical numbers, most

notably the song and Drunken

Poet's Scene in Act I, "Ye

gentle spirits” in Act III

and “The Plaint” in Act V.

This recording follows the

1693 text.

The score for The Fairy

Queen was lost within

a few years of its premiere:

revivals were thus limited

to the performance of afew

songs in concert and the

staging of a single act on 1

February l703 at Drury Lane

Theatre. The score was not

recovered until the

beginning of the 20th

century, when it emerged in

the collection of The Royal

Academy of Music, London.

Published song collections

identity some of the

original singers, and reveal

that they covered several

roles each, a practice which

has been observed in tlrrs

recording.

Stage

Conventions

Many

Restoration stage works were

adaptations of earlier

plays. and The Fairy

Queen was no

exception, for it was based

upon Shakespeare's A

Midsummer Nicht's Dream.

Although retaining much of

the original plot concerning

the four star-crossed lovers

and the intrigues of Titania

and Oberon, the adaptor

(probably Betterton himself)

seems to have taken

unpardonable liberties, for

not only is a substantial

portion of Shakespeare's

text cut or altered, but

none of his songs were set

by Purcell. The added

musical masques may seem, at

first glance, to be entirely

tangential to the drama. Why

would a professional actor

or writer be tempted to

tamper with the work of one

of the world's greatest

dramatists?

Shakespeare's text, in its

original form, did not

conform to Restoration

tastes. Indeed, the diarist

Samuel Pepys described a

1662 performance of A

Midsummer Night's Dream

as ‘the most insipid

ridiculous play that ever I

saw in my life.” In Pepy's

time, dramatic works which

integrated the songs,

dances, scenes and machines

of the court masque were

highly popular: Restoration

audiences would expect to see

wondrous visions, not merely

hear them described in

purple prose. Indeed, both

the prologue and preface to

The Fairy Queen

allude to this demand for

music, dance, scenes and

fancy costumes. Trap doors

enabled furies and demons to

rise and sink, and elaborate

machinery allowed gods to

descend in gold-gilted

chariots. Sets of grooves on

the stage floor permitted

the rapid change of sliding

scenery, which was always

done in full view of the

audience, for the curtain

was not drawn during the

performance. Although the

emphasis on spectacle was

not new, as the elaborate

descriptions for the early

17th-century court masques

designed by Inigo Jones

attest, it was a recent

development in the public

theatres.

Dance formed an important

part of the evening's

entertainrnent, and Purcell

was fortunate to have the

most acclaimed dancing

master of the time, Josias

Priest, who choreographed

all of Purcell’s major stage

works, as a colleague.

Priest worked in all the

current dancing styles,

which ranged from the

elegant cunring courtly

poses and floor patterns of

the rninuet to the more

varied and picturesque

postures required for the

technically challenging

grotesque dances, such as

that for the cane chairs in

Dioclesian, or for

the monkeys in The Fairy

Queen. Priest's talent

in using his whole body to

convey a character was

remarked upon by his

colleagues.

John Downes, prompter at

Dorset Garden Theatre,

confirms the appetite of his

contemporaries for

multimedia entertainments,

for he rernarks that The

Fairy Queen was

superior “in Ornarnents" to

Pnrcell's earlier dramatic

works, "especially in

Cloaths, for all the Singers

and Dancers, Scenes,

Machines and Decorations”

were "most profusely set

off”; the music and dances

were "excellently

perform'd”. The expense of

these spectaculars was

formidable, for despite the

fact that “the Court and

Town were wonderfully

satisfy'd” with The

Fairy Queen, “the

Expences in setting it out

being so great, the Company

got very little by it."

The lavish care devoted to

the visual aspects of stage

production caused dissension

within the theatre. Colley

Cibber a young actor in the

Dorset Garden company,

grumbled that "every aspect

of the Theatrical Trade has

been sacrific'd to the

necessary fitting out [of]

these tall ships of Burthen

[dramatic operas] that were

to bring home the Indies.

Plays were of course

neglected, Actors held

cheap, and slightly dress'd,

while Singers and Dancers

were better paid, and

enrbroider'd. These

Measures, of course, created

Murmurings on one side, and

Ill-humour and Contempt on

the other." English actors

were fated to he

malcontents, as the taste

for sensual splendour did

not abate.

Sensuality was indulged on

both sides of the proscenium

arch, in a heady atmosphere

in which women, both as

performers and spectators,

came to play an increasing

role. Early arrivals at the

theatre could listen to the

First and Second Music while

buying their oranges and

gossiping with their

neighbours. Romantic

intrigues loomed large, and

courtesans scandalized their

more proper neighbours by

wearing masks to facilitate

their flirting. During the

performance members of the

audience even wandered unto

the stage; hence the

reference to “Beau-skreens”

in the Prologue. It is a

wonder they were not run

down by the elaborate

rnachinery. Indeed,

theatrical managers often

had to issue pleas

requesting that the

spectators keep clear of the

stage and passageways.

The role

of Music and dance in The

Fairy Queen

In

A Midsummer Night's Dream,

references to music and

dance underline the changes

in Titania’s and Oberon's

fraught marital

relationship: in II, i,

Oberon is commanded to avoi

his wife and her revellers

if he cannot “patiently

dance in our round” and in

IV i, they mark their

reconciliation with a dance.

Music is central to 0beron’s

trick on Titania as well,

for he squeezes the love

juice on her eyes after she

is lulled to sleep by a

song. Bottom, by waking

Titania with a song, becomes

the first object she sees,

and thus also the object of

her affection. The final act

of Shakespeare's play is

amplified by two nuptial

dances, one performed by the

rustics whose play has iust

entertained the Duke and his

court, the other by Oberon

and Titania.

In The Fairy Queen,

the musical interludes,

which are much more

extensive than those in

Shakespeare's play, draw

upon the tradition of the

court masque, in which the

entertainments are meant to

honour an important

personage. In Act I,

Titania’s Indian boy the

subject of her tiff with

jealous Oberon, is fêted

with a pastoral song. “Come

away". In Act II, the revels

celebrate Titania's status

as Queen. In Act III,

Bottom, as Titania’s new amour,

is treated to a full-blown

fairy masque. The

entertainment to celebrate

Oberon's birthday in Act IV

marks the reconciliation of

the fairy couple. The Act V

rnasque is a nuptial

celebration for the mortal

lovers which parallels the

final dances in

Shakespeare's play. The

Restoration masque is

notably cynical in tone, for

Hymen grumpily refuses to

bless the fickle and

feckless lovers, and must be

cajoled by a magnificent

scene change into fulfilling

his traditional function.

Despite the differences in

staging traditions, The

Fairy Queen preserves

much of the flavour of

Shakespeare's original play,

which featured a cast of

diverse characters, from

Bottom the bumpkin to the

aristocratic lovers, with

the hapless and sometimes

forlorn mortals being

juxtaposed with the proud

and mischievous fairies.

Purcell’s songs and dances

play a leading role in

underlining the levels of

contrast in the musical

adaptation.

In Act I, the elegant

contrapuntal duet, "Come,

let us leave the town" is

followed by the arrival of

the drunken poet. This

blundering bass, whose

musical stutter was meant to

allude to a contemporary of

Purcell's, the poet Thomas

D`Urfey; is tormented by

graceful fairies whose

lilting and graceful vocal

style sets off the more

robust efforts of their

hapless victim. The rhythms,

texture and melodic shape of

"Trip it, trip it" suggests

fairies dancing in a round;

the staggering rhythms and

jagged vocal style of the

poet's declaration “I'm

drunk" effectively depict

the doddering drunkard.

Although arguably the most

tangential addition to the

play, this scene is an

effective piece of drama,

for the fairies and poet

constantly interact. The

fluid musical structure,

which moves effortlessly

from air to chorus, freely

mixed with colourful

exchanges between the poet

and his tormentors, is

facilitated by Purcell’s

characteristically English

vocal style, in which

recitative and aria are not

as sharply differentiated as

they would be in

contemporaneous Italian

opera.

The tenor air “Come all ye

songsters", which opens the

fairy revels in Act II,

demonstrates Purcell’s more

florid vocal style. Its

ornate manner makes it an

appropriate tribute to

Titania's royal status. The

instrumental pieces which

frame the trio “May the God

of Wit inspire" are highly

picturesque, depicting

singing birds and an echo by

a deft use of rhythm and

texture. "Sing while we trip

it" and the fairy dance

which follows are

effectively evocative of the

fairy world. The scotch snap

rhythm with which Purcell

sets the words "trip it"

demonstrates his sensitivity

to the gestural potential of

music. The revels are

succeeded by a night scene,

in which the bright C major

tonality of the fairy realm

is replaced by the murkier

sounds of C minor. The airs

for Night, Mystery and

Secrecy become progressively

more decorative; Sleep's

muted and syllabic "Hush, no

more" is a rebuke of their

sensual over-indulgence. The

canonic structure of the

“Dance for the Followers of

Night” is quite

extraordinary; perhaps

Priest exploited the highly

imitative music in the floor

patterns and gestures of his

dances.

In Shakespeare's play,

Bottom's appreciation of

music extends to a request

for the "tongs and bones”;

in The Fairy Queen

he is fêted with courtly

airs, elegant symphonies and

fantastic scene changes. In

providing such a marvellous

entertainment for Bottom in

Act III, Purcell and the

textual adaptor are

magnifying the joke of

Titania's folly in loving

such a bumpkin. Upon

Titania’s command, the

fairies prepare for the

masque by changeing the

scene to a great wood with

rows of trees and a river.

Two dragons make a bridge

over the river "through

which two Swans are seen in

the river at a great

distance". After the

poignant air “If love’s a

sweet passion”, a symphony

accompanies the forward

movement of the swans, who

are transformed into

fairies. Purcell has written

an elegant gavotte for the

fairies, which is followed

by a vigorous entry for the

savages who frighten them

away (also known as the

“Dance for the Green Men".

The grotesque dance of the

savages stems from the

earlier court masque

tradition, in which antic

characters were introduced

to provide a chaotic

element; the restoration of

order at the end of the

masque was seen as a triumph

of diplomatic and martial

skills of the current

monarch. By Purcell’s time,

however, such scenes were

introduced chiefly to

display the mimic talents of

the dancers and to provide a

visual contrast with the

more elevated portions of

the entertainment.

The courtly atmosphere in

Purcell's fairy masque is

briefly resumed with “Ye

gentle spirits of the air".

Its ornate style contrasts

with the Dialogue for

Coridon and Mopsa which

follows, in which the

triadic melody and syllabic

setting of the text

establishes their rusticity.

The "Dance for the

Haymakers" is in a similar

vein. Court and pastoral are

united in die simple yet

elegant air “When I have

often heard young maids

cornplaining”: courtiers,

rustics and fairies can meet

and mingle in the pastoral

woodland setting.

Most appropriately, the

music in Act IV which

celebrates Oberon’s

birthday, is the most regal

in character, with trumpets

providing a martial

atmosphere. The extensive

operung symphony accompanied

yet another glorious scene

change, in which a garden of

fountains, complete with a

bower, statues and marble

columns was revealed. The

fountains spouted real

water, which fell "in mighty

cascades to the bottom of

the scene"; in the midst of

the stage was “a very large

Fountain, where the water

rises about twelve foot”.

Such fountain scenes

continued to be a popular

feature in London theatrical

entertainments for some

years to come.

The royal tribute, which

culminates in the majestic

chorus “Hail! Great

parent!", is succeeded by a

masque for the four seasons,

a popular theme in

contemporaneous French

drama. As Roger Savage has

suggested, this scene would

have been inspired by the

disruption of nature caused

by the rift between Titania

in Oberon: in A

Midsummer Night's Dream,

Titania alludes to the

alteration of the seasons,

in which “hoary-headed

frosts / Fall in the fresh

lap of the crimson rose". In

The Fairy Queen, the

musically distinct seasons

celebrate the reunion of the

regal fairy couple: spring

sings an elegant and

somewhat florid song,

whereas summer is

represented by a lively

dance-like tune. Purcell's

famed contrapuntal skills

are demonstrated in the song

for autunm, in which singer

and bassline are engaged in

an earnest dialogue. Winter

is depicted by a slow

descending chr'omatrc line

which suggests an aged

person bent double with

cold: the ascending line

which follows hints at a

yearning for the sun, and

warmth.

The final musical

entertainment is meant not

only as a wedding

celebration, but aiso to

dispel the scepticism of the

Duke, who does not believe

in fairies, Juno's arrival

in a machine drawn by

peacocks was a

characteristic Restoration

stage device. Most of the

arias in this scene are

florid and courtly in

character; as suited the

occasion.

The second part of the

entertainment is directed

toward Titania, as Oberon

announces the next scene

change thus:

Now let a new

Transparent World be seen,

All Nature joyn to

entertain our Queen.

Now we are reconcil'd, all

things agree

To make an Universal

Harmony.

An

entry is danced while the

scene darkens, then a

symphony accompanies the

illumination of the stage,

which reveals a Chinese

garden with arches, arhours,

hanging planm and exotic

fruits, birds and beasts.

The lighting effect itself

would have been quite a feat

in an age still totally

reliant on candles. The

scene which follows unites

oriental exoticism with

pastoral delights; this is

reflected in Purcell’s vocal

lines, for “Thus the gloomy

world” is highly ornate,

whereas “Thus happy and

free” receives a simple

syllabic setting. The

monkeys' dance in this scene

is part of the grotesque

stage tradition, and may

have featured some gymnastic

tumbling. The change of

metre is a typical device in

much anti-masque music, and

would have provided the

dancers with an opportunity

to vary their comic

gestures.

The choice of a chaconne as

the final dance for 24

Chinese was probably

influenced by Lullian French

opera, which frequently

ended with lengthy dances

which were suitable for

large numbers of performers,

and thus would have formed

an impressive finale. No

matter how important the

element of spectacle was to

Restoration audiences, it is

Purcell’s music which is

celebrated here, for the

score to The Fairy Queen

reveals him to have been a

true man of the theatre.

Sarah

McClive

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|