|

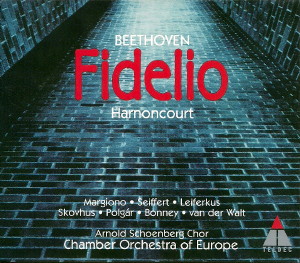

2 CD -

4509-94560-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

Ludwig van

Beethoven (1770-1827)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fidelio, Op. 72 |

|

|

|

| Oper in zwei Aufzügen -

Libretto: Joseph Sonnleithner, Stephan von

Breuning und Georg Friedrich Treitschke

nach Jean-Nicolas Bouilly |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ouvertüre |

|

7' 28" |

CD1-1 |

| ERSTER AKT |

|

63' 43" |

|

| - Nr. 1 Duett: "Jetz,

Schätzchen, jetz sind wir allein" -

(Jaquino, Marzelline) |

7' 28" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - Nr. 2 Arie: "O wär' ich schon

mit dir vereint" - (Marzelline) |

4' 56" |

|

CD1-3 |

| - Nr. 3 Quartett: "Mir ist so

wunderbar" - (Marzelline, Leonore, Rocco,

Jaquino) |

5' 12" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - Nr. 4 Arie: "Hat man nicht

auch Gold beineben" - (Rocco) |

4' 02" |

|

CD1-5 |

| - Nr. 5 Terzett: "Gut, Söhnchen,

gut" - (Rocco, Leonore, Marzelline) |

6' 37" |

|

CD1-6 |

| - Nr. 6 Marsch |

2' 53" |

|

CD1-7 |

| - Nr. 7 Arie mit Chor: "Ha,

welch ein Augenblick!" - (Pizzrro, Chor) |

3' 42" |

|

CD1-8 |

| - Nr. 8 Duett: "Jetzt, Alter,

hat es Eile!" - (Pizarro, Rocco) |

5' 24" |

|

CD1-9 |

| - Nr. 9 Rezitativ und Arie:

"Abscheulicher, wo eilst du hin" -

(Leonore) |

7' 57" |

|

CD1-10 |

| - Nr. 10 Finale: "O welche Lust"

- (Chor) |

6' 33" |

|

CD1-11 |

| - Nr. 10 Finale: "Nun sprecht,

wie ging's?" - (Leonore, Rocco,

Marzelline, Jaquino, Pizarro) |

7' 12" |

|

CD1-12 |

| - Nr. 10 Finale: "Leb wohl, du

warmes Sonnenlicht" - (Chor, Marzelline,

Leonore, Jaquino, Pizarro, Chor) |

3' 48" |

|

CD1-13 |

ZWEITER

AKT

|

|

47' 24" |

|

| - Nr. 11 Introduktion und Arie:

"Gott! - Welch Dunkel hier!" - (Florestan) |

5' 26" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Nr. 11 Introduktion und Arie:

"In des Lebens Frühlingstagen" -

(Florestan) |

4' 48" |

|

CD2-2 |

| - Nr. 12 Melodram un Duett: "Wie

kalt es ist" - (Leonore, Rocco) |

2' 02" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - Nr. 12 Melodram un Duett: "Nur

hurtig fort, nur frisch gegraben" -

(Rocco, Leonore) |

4' 43" |

|

CD2-4 |

| - Nr. 13 Terzett: "Euch werde

Lohn" - (Florestan, Rocco, Leonore) |

6' 14" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - Nr. 14 Quartett: "Er sterbe!"

- (Pizarro, Florestan, Leonore, Rocco) |

5' 46" |

|

CD2-6 |

| - Nr. 15 Duett: "O namenlose

Freude!" - (Leonore, Florestan) |

3' 49" |

|

CD2-7 |

| - Nr. 16 Finale: "Heil sei dem

Tag" - (Chor) |

1' 54" |

|

CD2-8 |

| - Nr. 16 Finale: "Des besten

Königs Wink und Wille" - (Fernando, Chor,

Rocco, Pizarro, Leonore, Marzelline,

Florestan) |

8' 35" |

|

CD2-9 |

| - Nr. 16 Finale: "Wer ein holdes

Weib errungen" - Chor, Florestan, Leonore,

Rocco, Marzelline, Jaquino, Fernando) |

4' 09" |

|

CD2-10 |

|

|

|

|

| Boje

Skovhus, Don Fernando,

Minister |

Barbara

Bonney, Marzelline, seine

Tochter |

|

| Sergei

Leiferkus, Don Pizarro,

Gouverneur eines

Staatsgefängnisses |

Deon

van der Walt, Jaquino,

Pförtner |

|

| Peter

Seiffert, Florestan, ein

Gefangener |

Reinaldo

Macias, Erster Gefangener |

|

| Charlotte

Margiono, Leonore, seine

Gemahlin, unter der Namen

"Fidelio" |

Robert

Florianschütz, Zweiter

Gefangener |

|

| László

Polgár, Rocco,

Kerkermeister |

|

|

|

|

| Arnold Schoenberg Chor /

Erwin Ortner, Chorus Master |

|

Chamber Orchestra

of Europe

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Gesamtleitung |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Stefaniensaal, Graz (Austria)

- giugno 1994 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Wolfgang Mohr / Helmut Mühle /

Michael Brammann |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec - 4509-94560-2 -

(2 cd) - 71' 11" + 47' 24" - (p) 1995 -

DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

"... a great paean to

marital love"

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt in conversation

with Anna Mika

Herr

Harnoncourt, your

interpretations of Beethoven's

music have met with tremendous

acclaim in recent years. Until

then you'd apparently been

exclusively concerned with

Baroque music and with Haydn

and Mozart. Was Beethoven a

natural progression? As a

conductor, how did you come to

Beethoven?

I'm often asked that

question. Many people seem to

think that, as a musician, I began at square

one and worked my way

progressively forward to the 19th

century and finally to the end of

the l9th century, but the truth of

the matter is that things were

rather different. My musical roots

lie in the late l9th and early 20th

century. We used to play chamber

music at home, and the earliest

pieces that we ever

played were in fact

by Beethoven. Mozart was regarded

as ancient. During the thirties my father also

used to play Gershwin at the

piano, in other words, at a time

when Gershwin's

music was still very new. When I was eighteen, I

thought I'd specialise in Dvořák

or Strauss.

If we went hack to pre-Classical

music with the Concentus musicus and even

hefore then, it was above all

because we felt that this music

was played in such a tedious way.

We looked for parallels with other

16th-, l7th- and 18th-century

arts, especially with painting,

sculpture and architecture, which

were so full of life at that time.

The Concentus musicus was founded

in 1953. Our very

first two concerts in 1957 were

conceived as a pair, one with

music from the court of the

Emperor Maximilian (in other

words, from around l500) and the

other with music by Haydn. So you see

that the Classical period was represented

from the outset. But quite apart

from my work with the Concentus

musicus, I've never

lost interest in composers like

Schubert who influenced me as a

child. So I simply can’t say at

what point I began to take an

interest in such and such a

composer. Works that interest me -

Porgy and Bess, The

Rake's Progress and Wozzeck,

for example - are constimtly on my

desk. My preoccupation with

Classical and pre-Classical works

doesn’t cut

me off from all

that came later in music. I can't

make music as though I were living

in some 17th- or 18th-century vacuum. Every

piece of music is relocated in the

present: it has to be meaningful

to the people who are alive today.

It's a concert

performance of Fidelio that you're conducting

in Graz, isn't it?

Fidelio is the one opera I

can most easily

conduct in the concert hall, since

it contains so much that's

reminiscent of an oratorio. Fidelio

is sui generis as an

opera, without precursors or

successors. You can’t

say that it's a German Singspiel

in the tradition of Die Entführung

aus dem Serail and Die

Zauberflöte.

It simply

doesn't fit into that sequence.

The demands

that Beethoven made of any text were

very strict, but I don’t think

they were the sort of criteria that we

ourselves would apply to opera libretti. He wanted

to write other operas. but he was

so sensitive on the matter of the

words that I’m

inclined to think that he would

have reinvented opera from his own

perspective rather than

conforming to the prevailing

trend.

So there's no sequel?

No. Or, if

there is,

possibly in Weber. You can detect a

powerful

influence in Der Freischütz

and Euryanthe. There's something

very forward-looking,

I feel,

about these works.

Beethoven has

often been reproached for

making the scene in Rocco's

house in Act One too

Singspiel-like in character.

There are two errors

bound up

with that remark, First, it belittles the

German Singspiel. Die Entführungs

aus dem Serail is a very

serious piece, but it's still a

Singspiel, and was even described

as an operettaby Mozart. Second,

the atmosphere in Rocco’s house in Fidelio

is shown to be profoundly oppressive from a musical

point of view: the relationships,

conditions and characters that are

portrayed and hinted at are all

extremely complex. And then there is

this sense of tension: what would

happen if the plot were to hang

fire? Leonora would have to many

Marcellina that very day, there's

absolutely no escape for her.

The numbers that are dismissed as being

Singspiel-like in character are

actually quite diffcrcnt. On a

superficial level, Beethoven

adopts the tone of a Singspiel,

but only in order to undercut it

by novel musical means. When Marcellina sings

the words “Fidelio hah ich gewählet", it

suddenly sounds as if it is

Leonora who is singing, and we are

left staring into an abyss. And

the conflict between Marcellina and

Jaquino is more than simply an amusing little tiff

over an ironing-board; that it is

a bitter conflict is clear from the music.

Beethoven's Fidelio is very often

misunderstood, as you can tell

from the occasions on which it is

given: it tends to be performed at

times of

political change - here in Graz,

for example, it was staged in 1933 as a

pro-National Socialist

demonstration, in 1945 as an

anti-National Socialist gesture to

mark the country's liberation from

Nazi rule, in 1956 to celebrate

post-war reconstruction, and so on

and so forth.

Oppression, imprisonment and

liberation are then emphaised. But for

Beethoven these were only a means

to an end. What he was concerned

about is love. The real action is

between Leonora and Florestan.

Essentially, the work is about

what can be achieved by true love

and the fact that a loving wife is

ready to do anything for her husband.

Dramatically speaking, the tnost

interesting character is without

doubt Rocco. He is the only character

who is fully drawn from a

psychological point of view. All

the other characters have only the

characteristics necessary for them

to play their parts within the

overall drama. In Rocco's case we

have before us a man whose reasons

for acting in such and such a way

are readily understandable. We can

recognise the conflicts and the

way in which he shuts his eyes in

the face of his

own complicity. Here is a

character with whom all who have

lived through the last sixty years

and not been completely blind to

all that was going on are bound to

sympathise. But he has another

side to him, a side that comes out

in his Gold Aria. It`s not as an

operatic bass that he speaks of gold.

Beethoven uses sophisticated

rhetorical figures in the

orchestra and striking metres to

show that Rocco is

obsessed with gold to the point of

madness and that he cracks up

completely the moment he gets his

hands on gold. Perhaps he gambles.

There’s something quite uncanny

about the way this is portrayed in

his aria - the way it turns into a genuine and

macabre waltz-like dance or the

way Rocco repeats words and, at

the same time, becomes quieter and

quieter until his whole body

starts to twitch once again at the

words “Das Glück

dient wie ein

Knecht für Sold" (For

fortune serves its

master like a valet). I regard this aria

as a mirror held up to the

listener with almost brutal force,

and I`m firmly convinced that it is

related to the German Singspiel on

only the most superficial level,

inasmuch as it takes over its

form, so that the listener is

consciously misled. Even the

overture, which is frequently

dismissed as a lightweight Singspiel overture, is a

very serious piece, a worthy

introduction to the work as a

whole.

In the case of the other

characters, one might think that

it was clear which are on the

side of good and which on the

side of evil.

I don’t see

it in that way. For example, we dont know

on which side the prisoners are.

When I read the

text and score, I have the

distinct impression that Florestan, the

minister and Pizarro

have known each other for a very

long time and that they weren't always

enemies. Indeed, one might

even suppose that they’re former

friends, almost cronies, perhaps

from their days in the army or as

students. They`re depicted as

though they have a common past, so

that each of them naturally knows

everything about the others.

Perhaps politics came between them, perhaps a

crime. At all events, the moral

dimension of the characters is not

clear, except at the moment when

Florestan says in his aria that he

was not prepared to hush something

up - hut what?

What matters as far as the plot is

concerned is that Florestan is in

a hopeless situation, that he

trusts in his wife and that

Leonora is ready to do anything

for him, even what appears

impossible. This opera is a great

paean to marital love. All the

other elements in the plot simply

serve to underline that point. It

runs counter to Beethoven's ideas

to try to turn it into an opera

about oppression arrd liberation.

And the final

scene? Does it have this ideal

and transfiguring quality for

you, too?

Oh yes! lt’s clearly

related to the final movement of

the Ninth Symphony and to passages

from the Missa solemnis.

It's traditional interpolate

the Leonore no. 3

overture between the Dungeon

Scene and the final tableau. But

not in your performances.

Beethoven wanted the

duet "O namenlose Freude"" to lead

straight into the final scene. He

said that there should be no more

than seven seconds between these

two pieces. I

think that's asking a bit much of the designer and

director. Generally it`s thought

that the time needed to rebuild

the set can be filled with the

glorious music of the Leonore

no. 3 overture.

But that's a

very bad idea

and one, moreover, that seriously

disturbs the tempo relationships

of the work. All

three versions are in agreement on

this point: the duet and the

march, “Heil sei dem Tag", have

exactly the sarne tempo marking,

which means that the duet should be taken more

slowly and the march more quickly

than usual. Dramaturgically

speaking, this makes a great deal of sense: the

jubilation

of the lovers is still coloured by

the suffering they`ve been through, it's not just

ecstatic but also inward, whereas

the jubilation

of the finale is like an explosion

liberating all the characters'

pent-up feelings. You can’t say

that Beethoven simply made a

mistake and that the duet should be taken more

quickly. (Of course, you can

always find excuses if you want to

take the two pieces at different

speeds.) This

clash between the two scenes was

very important to Beethoven and

has nothing to do with the world

of superficial reality.

If the final

scene is a vision - an oneiric

vision -, then it bas a

counterpoint in the quartet in

Act One.

Yes, the words of this

quartet have nothing to do with

the music. Each

of the four characters is given

different words to

speak and is in a totally

different relationship to the

action, and to the same music. I

think the word that best defines this

music is “wonderful”. Nowadays we

say something is wonderful when it

is very beautiful; but essentially

the word means everything

that makes us feel wonderment,

everything that rs incomprehensible. I think that even

in the introduction on the lower

strings every listener must feel

that sornething incomprehensible is happening

here. The characters are

transformed.

We must never

lose sight of the fact that

linguistic usage has changed since

Beethoven's day The word wunderbar

is a good exarnple of this. Much

the same is true of the words in

the Dungeon Duet when Rocco says:

"Nur hurtrg fort, nur frisch

gegraben" (Now quickly, get to

work and dig). Nowadays the words

frisch and hurtig

suggest joviality and ease. You

need only follow the linguistic

usage of the time for everything

to make sense.

We've come to

expect very dramatic voices in

this opera. But we know that

the first two Leonores, Anna

Milder and Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient,

were still very young. How

do you yourself see this

problem?

Beethoven also had

very young female singers for the

Ninth Symphony and Missa

solemnis. The boundaries

between the dilferent types of

voice were far less clear-cut than

they are today; so that a soprano

could just as easily sing Leonora

as Konstanze. The great singers

learned their repertory at a very

much earlier age, achieving an

ideal that they then maintained

for an long as they could. They

didn't try to develop in the way that

today's singers do between the

ages of 20 and 40,

when their

voices become

increasingly large, increasingly

heavy and increasingly inflexible.

And they certainly didn't sing as

loudly as they do

now. On the whole, vocal

technique seems to have been

very good: the vocal manuals

ofthe time are incredibly

demanding, and many singers sang

the same roles over a period of

many years.

I’m sure that works like the

Ninth Symphony and Missa

solemnis and arias such

as those of Leonora and

Florestan were not sung and

played as tremendously loudly as

they are today.

In all, there are three

different versions of Fidelio.

Have you ever thought of

performing one of the earlier

versions?

I've thought about it a lot. But at

present it would be of only

historical interest for me to

perfonn any other version than

the last - perhaps in order to

show how Beethoven arrived at

the final result. Such a

pedagogical approach to

practical music-making is

foreign to my nature. That’s

something I prefer to do at my

desk. I find many things in the

first and second versions that

are extremely interesting and,

as a first attempt, magnificent,

just as

one’s first idea is often the

best. One senses that the Fidelio that

is familiar to us is not the

product of

a single period and that

Beethoven developed

stylistically. I also believe

that he himself did not want all

these changes. In the course of

a famous session, all his

friends and all those who thongt

they had something to say on the

subject

persuaded him to alter, cut and

omit things. In several numbers

odd bars or groups of bars were

cut. Of course, the numbers that

were newly written in the wake

of this revision are absolutely

wonderful.

I don’t

think Beethoven regarded the

first version as entirely

successful, otherwise he

wouldn't have agreed to other

peoples suggestions for changes.

On the other hand, we know that

not all the changes reflect his

own intentions and that he

agreed to them only reluctantly

in order to salvage the work. In

other words, the version that

Beethoven really wanted simply

doesn’t exist. Someone with a

hotline to Beethoven - or with a

great deal of sensitivity -

should try to work out what

Beethoven himself wanted and

what was forced upon him. We'd

then have an optimal Fidelio

based on the three existing

versions. I

once considered doing it, but

the challenge was too great.

Herr Harnoncourt, perhaps

you'll allow me to end by

asking a general question. To

date you've written

three books, and in all of

them you express a pronounced sense

of cultural pessimism. But

in rehearsal you reveal

the greatest possible

enthusiasm for making

music. How do you

reconcile these two

aspects?

I’m really very

pessimistic. On the other hand,

I think that it`s impossible to

say whether there may yet be

ways that we don`t know. If you

do something, it must be with

the last ounce of commitment and

with total enthusiasm, and

enthusiasm isn't

lessened by pessimism.

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|