|

2 CD -

4509-94555-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

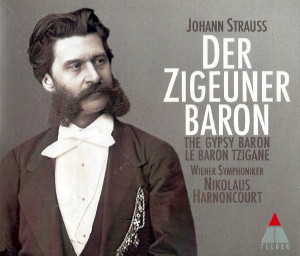

Johann

Strauss (1825-1899)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Der Zigeuner Baron |

|

150' 04" |

|

Operette in drei Akten -

Libretto: Ignatz Schnitzer nach einem

Roman vpn Marius Jókai

|

|

|

|

| Fassung von Nikolaus

Harnoncourt und Norbert Linke nach den

Originalvorlagen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ouvertüre |

|

8' 30" |

CD1-1 |

ERSTER

AKT

|

|

66' 19" |

|

| - Nr. 1 Introduktion |

1' 10" |

|

CD1-2 |

| - "Das wär' kein rechter

Schifferknecht" - (Chor) |

1' 02" |

|

CD1-3 |

| - "Jeden Tag Mü' und Plag" -

(Ottokar, Zsupán, Czipra) |

1' 21" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - Melodram: "Zum Teufel! Wieder

die alte Hex!" - (Zsupán, Czipra, Ottokar,

Chor) |

2' 42" |

|

CD1-5 |

| - Nr. 2 Entrée-Couplet: "Als

flotter Geist und früh verwaist" -

(Barinkay, Chor) |

2' 41" |

|

CD1-6 |

| - Dialog: "Nun denn, mein

wackrer Changeur" - (Carnero, Barinkay) |

2' 25" |

|

CD1-7 |

| - Nr. 3 Melodram und Ensemble:

"Herrgott, ein altes Weiß!" - (Carnero,

Czipra, Barinkay, Saffi) |

4' 10" |

|

CD1-8 |

| - Nr. 3 Melodram und Ensemble:

"Zum Reichtum gratulier' ich Euch" -

(Carnero, Czipra, Barinkay, Chor) |

2' 40" |

|

CD1-9 |

| - Nr. 3 Melodram und Ensemble:

"Hier bin ich" ... "Ja das Schreiben und

das Lesen" - (Zsupán, Carnero, Chor) |

3' 23" |

|

CD1-10 |

| - Dialog: "Wir wollen offen

miteinander reden!" - (Barinkay, Zsupán,

Carnero, Mirabella, Ottokar) |

3' 03" |

|

CD1-11 |

| - Nr. 4 Couplet der Mirabella:

"Just sind es zweiundzwanzing Jahre" -

(Mirabella, Chor) |

3' 53" |

|

CD1-12 |

| - Nr. 5 Ensemble: "Dem Freier

naht die Braut" - (Chor, Arsena, Barinkay,

Zsupán, Carnero) |

3' 25" |

|

CD1-13 |

| - Nr. 5 Ensemble: "Bitte zu

versuchen!" ... "Hochzeitskuchen" -

(Mirabella, Chor, Barinkay, Carnero,

Arsena, Zsupán, Ottokar) |

4' 04" |

|

CD1-14 |

| - Dialog: "Mein Mädel gefällt

dir also?" - (Zsupán, Barinkay, Ottokar,

Arsena) |

1' 31" |

|

CD1-15 |

| - Nr. 5a Sortie: "Ein Falter

schwirrt ums Licht" - (Arsena) |

1' 07" |

|

CD1-16 |

| - Nr. 6 Zigeunerlied: "So elend

und so treu" - (Saffi, Barinkay) |

5' 57" |

|

CD1-17 |

| - Dialog: "Ich kenne die Weise!"

- (Barinkay, Czipra, Saffi) |

0' 59" |

|

CD1-18 |

| - Nr. 7 Finale I: "Arsena!

Arsena!" - (Ottokar, Arsena, Barinkay,

Saffi, Czipra) |

3' 46" |

|

CD1-19 |

| - Nr. 7 Finale I: "Dschingrah,

Dschingrah" - (Chor, Barinkay, Czipra,

Saffi) |

3' 05" |

|

CD1-20 |

| - Nr. 7 Finale I: "Wie

wechselvoll beteilt mein Schicksal" -

(Barinkay, Czipra, Saffi, Chor) |

2' 57" |

|

CD1-21 |

| - Nr. 7 Finale I: "Nun zu des

bösen Nachbarn Haus" - (Barinkay, Zsupán,

Arsena, Mirabella, Carnero, Saffi, Czipra,

Chor) |

4' 14" |

|

CD1-22 |

| - Nr. 7 Finale I: "Wojwode der

Zigeuner?" - (Chor, Barinkay, Arsena,

Ottokar, Carnero, Mirabella, Zsupán,

Saffi, Czipra) |

6' 43" |

|

CD1-23 |

ZWEITER

AKT

|

|

54' 48" |

|

| - Zwischenaktmusik |

1' 36" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - Nr. 8 Terzett: "Mein Aug'

bewacht" - (Czipra, Barinkay, Saffi) |

4' 49" |

|

CD2-2 |

| - Nr. 9 Terzett: "Ein Greis ist

mir im Traum erschienen" - (Saffi,

Barinkay, Czipra) |

2' 26" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - Nr. 9 Terzett: "Ei, ei, er

lacht" - (Saffi, Czipra, Barinkay) |

1' 35" |

|

CD2-4 |

| - Nr. 9 Terzett: "Da klingt es

hohl" - (Barinkay, Saffi, Czipra) |

3' 22" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - Nr. 10 Ensemble: "Auf, auf,

auf! Vorbei ist die Nacht" - (Pali) |

0' 57" |

|

CD2-6 |

| - Nr. 10 Ensemble: "Ha, das

Eisen wird gefüge" - (Chor) |

2' 53" |

|

CD2-7 |

| - Dialog: "Ah, das ist ja

großartig" - (Barinkay, Carnero, Zsupán, Mirabella,

Arsena) |

1' 07" |

|

CD2-8 |

| - Nr. 11 Duett: "Wer hat Euch

denn getraut?" - (Carnero, Barinkay,

Saffi, Chor) |

4' 44" |

|

CD2-9 |

| - Nr. 12

Sittenkommissions-Couplet: "Ich will Euch

... Nur keusch und rein" - (Carnero,

Mirabella, Zsupán, Chor) |

4' 11" |

|

CD2-10 |

| - Dialog: "Vater! Vater!" -

(Ottokar, Mirabella, Zsupán, Carnero, Arsena,

Barinkay, Homonay) |

1' 05" |

|

CD2-11 |

| - Nr. 12 1/2 Couplet: "Mur

helfen die Doktoren nicht" - (Zsupán) |

3' 34" |

|

CD2-12 |

| - Dialog: "Beruhigen Sie sich,

meine Damen" - (Homonay, Carnero, Barinkay, Saffi, Czipra) |

1' 58" |

|

CD2-13 |

| - Nr. 13 Finale II: "Nach Wien?"

- (Carnero, Zsupán, Mirabella,

Ottokar, Arsena, Homonay) |

2' 24" |

|

CD2-14 |

| - Nr. 13 Finale II: "Was gafft

ihr noch? Ergreifet sie!" - (Carnero,

Barinkay, Czipra, Homonay, Chor) |

1' 08" |

|

CD2-15 |

| - Nr. 13 Finale II: "Hier die

Hand, es muß ja sein" - (Homonay, Barinkay,

Chor) |

3' 40" |

|

CD2-16 |

| - Nr. 13 Finale II: "Noch eben

in Gloria" - (Carnero, Zsupán,

Mirabella, Arsena, Ottokar, Czipra,

Barinkay, Homonay, Saffi, Chor) |

3' 29" |

|

CD2-17 |

| - Nr. 13 Finale II: "O welch ein

Glück!" - (Saffi, Barinkay, Chor, Czipra,

Homonay, Ottokar, Zsupán, Arsena,

Mirabella, Carnero) |

7' 49" |

|

CD2-18 |

| - Nr. 13 Finale II: "O voll

Fröhlichkeit" - (Saffi, Arsena, Mirabella,

Czipra, Barinkay, Ottokar,

Zsupán, Homonay,

Carnero, Chor) |

1' 56" |

|

CD2-19 |

DRITTER

AKT

|

|

20' 27" |

|

| - Zwischenaktmusik |

1' 36" |

|

CD2-20 |

| - Nr. 14 Chor: "Freuet euch,

freuet euch" - (Chor) |

0' 46" |

|

CD2-21 |

| - Dialog: "Ist es also wahr?" -

(Mirabella, Arsena,

Carnero) |

1' 11" |

|

CD2-22 |

| - Nr. 15 Couplet: "Ein Mädchen

hat es gar nicht gut" - (Arsena, Mirabella, Carnero) |

4' 14" |

|

CD2-23 |

| - Dialog: "Allen Respekt! Sie

wissen genug" - (Carnero,

Mirabella, Homonay) |

0' 55" |

|

CD2-24 |

| - Nr. 16 Marsch-Couplet und

Chor: "Von des Tajo Strand" - (Zsupán, Chor) |

1' 53" |

|

CD2-25 |

| - Dialog: "Ja mein Gott, ich

könnte" - (Zsupán,

Mirabella, Carnero, Arsena) |

0' 40" |

|

CD2-26 |

| - Nr. 17 Einzugsmarsch: "Hurrah,

die Schlacht mitgemacht" - (Chor) |

3' 07" |

|

CD2-27 |

| - Dialog: "Ihr alle, alle habt

wacker" - (Homonay, Barinkay, Mirabella) |

1' 02" |

|

CD2-28 |

| - Nr. 18 Finale III: "Heiraten,

Vivat!" - (Chor, Barinkay, Arsena,

Mirabella, Ottokar, Zsupán, Carnero,

Homonay, Saffi, Czipra) |

3' 29" |

|

CD2-29 |

| - Nr. 18 Finale III: "Als

flotter Geist und früh verwaist" -

(Barinkay, Saffi, Arsena, Mirabella,

Czipra, Ottokar, Zsupán, Homonay,

Carnero, Chor) |

1' 34" |

|

CD2-30 |

|

|

|

|

| Herbert Lippert,

Sándor

Barinkay |

Christiane Oelze,

Arsena |

|

| Pamela Coburn,

Saffi |

Elisabeth von Magnus,

Mirabella |

|

| Rudolf Schasching,

Kálmán Zsupán |

Hans-Jürgen

Lazar, Ottokar |

|

| Julia Hamari,

Czipra |

Jürgen

Flimm, Conte Carnero |

|

| Wolfgang Holzmair,

Graf Homonay

|

Robert Florianschütz,

Pali |

|

|

|

| Arnold Schoenberg Chor /

Erwin Ortner, Chorus Master |

|

Wiener Symphoniker

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Gesamtleitung |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Konzerthaus, Vienna (Austria)

- aprile 1994 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Wolfgang Mohr / Helmut Mühle /

Michael Brammann |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec - 4509-94555-2 -

(2 cd) - 74' 49" + 75' 15" - (p) 1995 -

DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

A document unknown to all

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt in conversation

with Monika Mertl, Vienna, 20 april

1994

"Tradition is

slovenliness" - is that a

sentiment that applies

particularly to Der

Zigeunerbaron?

The phrase you've just quoted

comes from a fairly complicated

sentence by Mahler. I think many

forms of slovenliness

can be described

as traditional. But I don’t regard genuine tradition

as slovenly.

In the case of

Zigeunerbaron, genuine

tradition would mean knowing

where this music comes from.

Just as Alban Berg's

transcriptions - including, for example,

his wonderful version of the

Treasure Waltz for piano

quintet - sound for all the

world to come from Schubert.

That’s right. And you can

also hear how this music develops into Alban Berg. It comes

from Schubert and goes to Berg. This is

particularly clear in the case of Die Fledermaus, but

the same is true of Der

Zigeunerbaron, which is

undoubtedly a key work. I'm especially

attracted by

this mixture of opera and operetta

and by the way the melodramas are

treated - in

short, by the work’s intermetliate

position. It reminds me of what

people say about Schubert's

operas - that

there are no arias in

them and that he wrote only

orchestral songs. But where does it

say when an aria is an aria and when

it is a song. I find it unbelievably beautiful.

Mozart called Die Entführung

an operetta and you could equally

well say that it, too, tends in the

tlirection of what was later to be

called operetta.

Der Zigeunerbaron has a

performing tradition that you

yourself got to know during your

time as an orchestral musician.

All kinds of things must have

crept into the tradition.

Yes, every other conductor changes

the instrumentation, adding a couple

of horns, altering the timpani parts and so

on. During the late forties and

early fifties I often played in the

Volksoper orchestra. The conductors

there certainly knew this sort of

music inside-out, but there wasn't a

single score that they left

untouched. I can also rememher that

whenever we played Johann Strauss

with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra.

it was always in some arrangement or

other.

What was it in particular that

you didn't like about the current

version of Der Zigeunerbaron?

I was disturbed by the fact that it

was so obviously cobbled together. I had no sense of

architectural structure in the piece, but felt that

there were holes in it. I wanted to

know whether this wonderful music

was really arranged in the order in

which it`s always heard. It struck me, for

example, that Homonay's

Recruitment Song had been removed

from the finale and placed before it

as an independent number. When you

see what the finale really looks

like, with this Recruitment Song

repeated three times,

each time differently orchestrated,

you realize what a fantastic form it

is. You can’t help noticing the

scissors and paste. It was a question of changing the

characters - a little less fear of

the war, a little less shirkrng. The brutality of the

recruitment and the pitiful reactions of Zsupán and Ottokar after

they`ve already enlisted: “I will

make peace with the enemy" - such

words are tantamount to an

incitement to refuse to fight in the

war. And that was certainly

unwelcome at that time. The words

don’t agree either. There's a

censored version of the libretto. It's incredibly

interesting to see what the censor

wanted and what he didn`t want. You

can see how the piece was rewritten

with the clear aim of inspiring a

sense of enthusiasm for the war. And

then I was disturbed, of course, by

what people read into the work in

performance - this embarrassing,

superficial patriotism and the

ridrculousness of the gypsies. In

Strauss's original, the world of the

gypsies is

depicted with tremendous affection.

But isn't there

a great deal of false gypsy

romanticism in the piece?

Well, I'm not sure

I'd describe it as false: there's

certainly the charm of the exotic,

of the person for whorn hearth and

home aren't essential - tlrat’s a

very old idea. For me, it begins

with Mignon. What is she in Goethe?

A gypsy? A creature

whom we don’t understand and who has

dark thoughts, but who is

fascinating, who attracts us and

who, at the same time, makes us

afraid. In much

the same way, the gypsy world in

this operetta is shown to exert a

magical fascination.

An you think that all the

patriotism and enthusiasm for war

that are contained in the piece,

with its jollycomrade's mentality,

were not intended by Strauss, at

least not in this form?

In the form in which we know it,

with Homonay

immaculate in his irreproachableness, most

certainly not. We can’t tell, of

course, whether there is any irony

here. But what I do see is that the

Recruitment Song has a rhythm that

had already existed in Austrian and

Hungarian music for

over a hundred years. The Hungarians call it verbunkos, which

is derived from the German word Werbung

(recruitment). This is the kind of

music that the Band of Hussars used

to play in order to persuade young

peasants to enlist. In the Hungarian

consciousness, this rhythm is the

epitome of cruelty. for if someone had said he was

going to enlist and then calmly

announced that he had no intention

of going through with it, he was already regarded as a

deserter and could be sentenced to

death. Needless to say; there

are plenty of wordless

examples

of this use of the verbunkos

to symbolize

cruelty in classical music, the most famous instance

being the final movement of the "Eroica" Symphony. On the

other hand, one shouldn't draw excessively

modern conclusions on the strength

of historical hindsight.

Two particularly crucial

types of modern conflict are found

in the piece and concern our

attitudes to foreigners and to brute force

and war. You could say that Johann

Strauss’s own attitude was at odds

with that of his age, but you could

also say, of course, that in

claiming this, we are guilty of

examining the problem too much from

our own perspective.

But I don't

think you could claim that

Strauss's attitude was

politically correct, at least

in today's terms.

Not in todays terms. But it

really is very cruel. We forever

expect people of other

periods to show insights unique to

our own.

Of course, one can't

expect that. But what is so

fascinating about great works is

their ability to keep pace with

present-day insights.

Well, I suppose so, but it

could also be a case of our

inability to keep pace with their

insights. After all, who's to say what the

right pace is? History is history As a

member of a generation that has

lived to see an absolutely

unbelievable range of human

possibilities opening up, I, least

of all, am in a position to say that

someone should have acted in such

and such a way.

But we're concerned not with

moral standpoints but with the

fact that the human relationschips

in Mozart's operas, for example,

although formed so long ago, still

strike our modern sensibilities

as...

That’s absolutely

right. And you can go back another

two hundred years

and find exactly the same in Monteverdi.

But in the case of

Der

Zigeunerbaron it symply doesn't

conform to our modern critical

attitudes...

No, not in the slightest.

What's involved

here is what I'd describe as

naive patriotism.

Or else an

interpretation of it. It may be even

more cryptic than Cosě fan tutte

or Figaro. I mean, if you

take it at face value, it's

radically different from anything we

might think today. But if you were

to regard it as extremely

subversive, you might well be

disposed to agree with it. I do

believe that the work contains this

range of possibilities.

Although we can't reconstruct

Strauss's intentions.

Exactly. I'm wary about

saying that it really is so

subversive and that it sets out to

prove the opposite of what it seems

to. But this

whole enthusiasm for war takes on a

different aspect when you take

account of the symbolic language of

the verbunkos music That's

what I mean when I

say “subversive", namely, that in

many of the statements that puzzle

us there may well lurk other

possibilities and that these

possibilities were there from the

outset.

The material that you've now

discovered and incorporated into

the score is qualitatively beyond

reproach?

Beyond reproach. And it's not strictly true

to say that it has been rediscovered

and incorporated into the score, but

that only when it was taken out do

you notice the artificial joins. As

soon as you restore it, everything

sounds right again.

And Zsupán couplets

that Alexander Girardi sang at the

premičre are now heard at the point where

Homonay's Recruitment Song has

otherwise always come?

That emerges from the

dialogue that comes before it.

Ottokar and Zsupán

have just

enlisted, and Zsnpán

now wants to

extricate himself from the whole

affair, whatever the cost, and so he

invents a whole

series of illnesses. It`s a

completely unknown passage: “No

doctor can help me now, I am lost! My chest is much too delicate, my lungs

are in disgrace!" It’s a wonderful

piece of music.

And also a very fanny number.

I really can’t understand why people ever

thought of cutting it. But I imagine that it was the censor who

cut it, since the

idea of a coward or malingerer was

intolerable.

What does the

music say about the characters?

You have to be careful here not to

apply the wrong standards. But there

are certain things I think I can

infer. Mirabella's

conplets, for example, tell me that

she has plainly had a child by every

man with whom she has come into

contact. I personally am convinced - on the strength of

the music that she sings - that she has had

at least one child by Carnero, so

that Ottokar may have another

brother or sister. She certainly has

one by the Pasha with whom she lived

in Belgrade, and she also has one by Zsupán. So there are at

least three.

Barinkay is fairly well

characterized musically, But I can’t

always tell in his case whether his

music is operating on two different

levels. Everything

in the words is also

written into the music. An attempt

has been made to make him appear

less than wholly sympathetic. Even his entrance

number depicts him as utterly

unrestrained. The way he reacts to

Arsena and switches from her to

Saffi is completely unfeeling.

There's not a trace of emotion

behind it. Whereas in Saffi's ease - and this is

typical - there is a mass of emotion

present.

In the manner of her rejection - and this comes out

in the music, too - Arsena is

immensely sympathetic, not least as

a result of the determination she

shows in refusing to allow herself

to he used for her father`s dynastic

ends.

Musically speaking,

what strikes me most of all is the

way in which Barinkay

is deprived of all his mystique. In

the refrain of his Entrance couplet, "]a, das alles, auf

Ehr`", the top A isn`t original.

It's found only at the end, in the

finale, when the chorus sings it as

well. On its

first appearance it`s a G. It’s

really distorting.

The A makes him more

radiant.

And the G makes him a bit more

pitiful.

And Zsupán is cast as a

tenor?

He's cast as a

tenor, just as he should be. In his duets

with Ottokar he even takes the upper

line.

And yet Zsupán

is regarded as a

traditional baritone role.

In

fact, he’s often even cast as a low

baritone, so that certuin

things have to be transposed down. "Ja, das Schreiben

und das Lesen" is very

often lower. And

this song has a vast

middle section, “Doch trinken sie

nicht minder”,

that's completely unknown. Girardi

must have been a character

tenor who came to operetta from

acting.

So you're once

again stirring things up in

Vienna?

Yes, I thought the existing version

was unlikely to be

changed in Vienna for the next forty

years. The ideas that literally

bubble to the surface from the

surviving sources ought to be taken up by the

Volksoper. After all, you can’t simply say, "Let's go on playing

this just as we’ve always done for

the next hundred years". That's why

I think it very

important that it should be done here. You must

first get to know it properly. At

least you then know what's being

criticized.

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt

Translation:

Alfred Clayton

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|