|

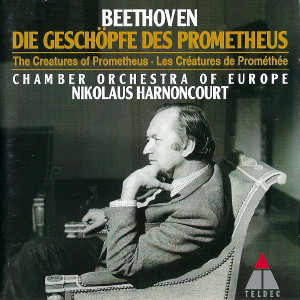

1 CD -

4509-90876-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

| Ludwig van

Beethoven (1770-1827) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus,

Op. 43 |

|

68' 41" |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ouverture: Adagio - Allegro

molto con brio |

5' 02" |

|

1

|

| Introduction: Allegro non troppo

- La Tempesta |

2' 14" |

|

2

|

| - I. Poco Adagio |

3' 34" |

|

3

|

| - II. Adagio - Allegro con brio |

1' 45" |

|

4

|

| - III. Allegro vivace |

2' 30" |

|

5

|

| - IV.

Maestoso - Andante |

1' 34" |

|

6

|

- V. Adagio - Andante quasi

Allegretto

|

7' 43" |

|

7

|

| - VI. Un poco Adagio - Allegro |

1' 24" |

|

8

|

| - VII. Grave |

4' 25" |

|

9

|

| - VIII. Allegro con brio |

7' 14" |

|

10

|

| - IX. Adagio |

4' 00" |

|

11

|

| - X. Pastorale: Allegro |

2' 44" |

|

12

|

| - XI. Andante Coro di Gioja |

0' 23" |

|

13

|

- XII. Maestoso Solo di

Gioja

|

3' 05" |

|

14

|

| - XIII. Allegro Terzettino

"Grotteschi" |

4' 10" |

|

15

|

| - XIV. Andante Solo della

Casentini |

5' 38" |

|

16

|

| - XV. Andantino Solo di

Viganò |

4' 49" |

|

17

|

| - XVI. Finale: Allegretto Danze

festive |

6' 22" |

|

18

|

|

|

|

|

| Chamber Orchestra

of Europe |

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Musikverein,

Vienna (Austria) - novembre 1993 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 4509-90876-2 - (1 cd) - 68' 41" - (p)

1995 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

The Creatures of Prometheus

or The Power of Music and Dance

|

The two

s[tatues] move slowly across the

stage from the background. -

P[rometheus] gradually regains consciousness, look

towards the field, and is

pleased when he sees his plan is

such a success; he is

inexpressibly delighted, stands

up and beckons to the children

to stop - They turn slowly

towards him in an emotionaless

manner. - P continues to address

them, expresses his divine and

fatherly love for them, and

commands them (gives them a

sign) to approach him. - They

look at him in an emotionless

manner - turn to a tree, the

great size of wich they

contemplate. - P begins once

more to be disheartened, is

fearful, and is saddened. He

goes towards them, takes their

hands and leads them to the

front of the stage; he explains

to them that they are his work,

that they belong to him, that

they must be thankful to him,

kisses and caresses them. -

However, still in an emotionless

manner, they sometimes merely shake their

heads, are completely

indifferent, and stand there,

groping in all directions.

Beethoven's

holograph copy of choreographical

notes

from the

scenario No. 1 contained in the

Berlin

"Landsberg 7" sletchbook

After Haydn had congratulated him on

the success of the Viennese premiere of

Die Geschöpfe des

Prometheus, Beethoven is said to

have exclaimed "That is

very kind of you, but it is not yet a

Creation by any stretch of the

imagirmtion!". Yet

it was a genuine compliment. After

all, despite some unfavourable

reviews, there were twenty

performances of the

music for Salvatore Viganò's ballet in

the 1801-02 season. Thus Beethoven was

not simply being presumptuous, for

the subiect, its treatment and above

all the close cooperation between the

choreographer and the

composer had led to a work for the

stage which in fact constituted an

attempt to transcend the symphony, the

oratorio and opera, thereby producing

a new kind of

theatrical genre that included both

music and dancing. This

“ballo serio"

(the subtitle on a copy made for

Beethoven) combines aspects of

the allegorical pantomime, of the

heroic ballet. and above all of a

quite novel kind of "musique

parlante" which, in

tone poems based on some kind of

programme, continues to be

eloquent even when words are no longer

present.

“Prometheus lifts the people of

his time up out of their ignorance,

makes them more refined through

scholarship and art, and gives them manners.

This in a few words constitutes the

subject matter." Without meaning to do

so, the otherwise ill-tempered review

of the first performance in the Zeitung

für die elegante Welt

put its finger on the ideas on which

the work is based. The earnestness

with which Beethoven sought to

understand and treat the dramatic

scenario is revealed not only by the

composition's strict adherence to

details of the plot, but also by the

central significance that the idea was

to retain in his compositional work for

years to come. Constantin Floros has

shown that the subject and structure

of Die Geschöpfe des

Prometheus op. 43 were

later elaborated in the Sinfonia

eroica, which was originally

designed as a svmphony about Napoleon.

However, the inner unity of

the ballet music

was already considered to be problenratical

in 1801,

especially with regard to the

characterization, the sequence of ideas,

and the formal structure. The review

cited above stated that Beethoven

“wrote too learnedlv for a ballet and

did not pay enough attention to the

dance, and this can hardly be called

into question. For a divertissement,

which is what the ballet is

really meant to be, everything was

much too large, and on account of

the lack of the

appropriate situations it was destined

to remain more a fragment than a

whole." Beethoven's conternporaries did

not know that this was a key work, nor

that the subject of Prometheus was

destined to play a role

in the Eroica, in the late works and,

as has sometimes been

claimed, in the Ninth

Symphony. All this

only became apparent

much later. For a long time Die

Geschöpfe

des Prometheus continued to be

thought of as ballet music, and as a

relatively unimportant early work at

that. Those who saw it as an example

of symphonic music ior the stage noted

a lack of "inner unity", which was

thought to be due

to the disparity between the

large-scale opening and final sections

of the two acts. and

the succession of short numbers

towards the end.

It is no longer

possible to give credence to the

notion that the plot cannot be

reconstructed, and that it is

therefore necessary to salvage the

work as "absolute music" (with this in

mind Hugo Riemann even argued in

favour of treating it

as an extended set

of variations). Above all there is

the evidence provided in

Beetboven's sketches, which

have now been reconstructed and deciphered,

by entries and remarks such as "les

trois graces... les enfants pleurent...

Prom. weint... mi presenta miseria",

and by a detailed holograph précis

of the plot that is based on the lost

scenario by Viganò. This

demonstrates the rondo structure of

No. l in a rather compelling

manner. Finally, there are the

headings in the vocal score checked by

Beethoven (e g. "Atto

II"), and information

relating to the dancers’ solos (Gioja,

Mme Casentini and

Viganò). All this

has made it possible to assign the

indiridual movements

to the dramatic structure of the

ballet. Furthermore, it corresponds to

the précis of the ballet transmitted

in Carlo Ritorni’s biography of Viganò,

which was published in Milan in 1838.

This text which has been supplemented

by Nikolaus Harnoncourt

does not give the exact succession of

the scenes, though it contains a

description of all

the numbers for

which Beethoven composed music (The

track numbers of this complete

recording of Beethoven's ballet music

have been inserted at the appropriate

places.)

In l8l3 Viganò

produced a six-act version of

his Prometheus chroreographv

for a performance at La Scala in

Milan. It included

additional material by Joseph

Weigl and parts of Haydn's The

Creation. It is

easy to understand why

Beethoven said that this particular

Prometheus gave him ‘no real

pleasure'. However,

in Milan the expanded version was

acclaimed as being the "solution of

the Faust problem", as a document of

the incontrovertible mastery of Viganò

(whom Stendhal rightly considered to

be one of the greatest geniuses of the

age), and as the beginning of a new

era of ballet. Nevertheless, both in Italy

and in Germany Beethoven's ballet

music failed to achieve lasting

popularity and remained a work of

historical interest only. Indeed,

it became a classic example of

attempts at historical reconstruction.

And thus Haydn’s answer to the

provocative comment cited above

unfortunately continues to be valid in

a musical world that

is only interested in a composer's

principal works: "That is true", he

objected, no doubt somewhat taken

aback at Beethoven's comparison of

his first stage work with his own late

masterpiece, "it is not yet a

‘Creation'; and [I] find

it difficult to believe that

it will ever become one."

Rainer

Cadenbach

Translation: Alfred

Clayton

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|