|

1 CD -

0630-10021-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

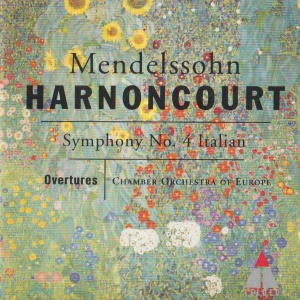

| Felix

Mendelssohn (1809-1847) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 4 in A major,

Op. 90 "Italian" |

|

28' 56" |

|

- Allegro vivace

|

10' 39" |

|

1

|

- Andante con moto

|

6' 45" |

|

2

|

- Con moto moderato

|

5' 50" |

|

3

|

- Saltarello: Presto

|

5' 42" |

|

4

|

| Overture "Die Hebriden",

Op.26 |

|

10' 18" |

5

|

| Overture "Die schöne

Melusine", Op.32 |

|

10' 53" |

6

|

| Overture "Ein

Sommernachtstraum", Op. 21 |

|

11' 46" |

7

|

| Overture "Die erste

Walpurgisnacht", Op. 60 |

|

9' 28" |

8

|

|

|

|

|

| Chamber Orchestra

of Europe |

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Teatro

Comunale, Ferrara (Italia) - ottobre

1991 (Symphony No. 4)

Stefaniensaal, Graz (Austria) - giugno

1991 (Overtures Op. 26 e Op. 32)

Stefaniensaal, Graz (austria) - luglio

1992 (Overtures Op. 21 e Op. 60) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

studio /

live (Overtures Op. 21 e Op.60)

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr & Renate Kupfer (Op. 21 e Op.

60) / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

Teldec

- 9031-72308-2 - (1 cd) - 69' 05" - (p)

1992 - DDD (Symphony No. 4)

Teldec - 9031-74882-2 - (1 cd) - 77' 55"

- (p) 1993 - DDD (Overtures Op. 21 e Op.

60)

Teldec - 0630-10021-2 - (1 cd) - 71' 50"

- (p) 1995 - DDD (Overtures Op. 26 e Op.

32)

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Poetic idea and musical

form

|

“So much is spoken

about music, and so little is said.

I'm convinced that words are

inadequate to describe it, and if

ever I were to find

that they were adequate, I’d give up

writing music altogether. People

normally complain that music is so

ambiguous and that what they are

supposed to think while listening to

it is so unclear, whereas everyone can

understand words." Thus

Felix Mendelssohn unburdened himself

in a letter to Marc-André

Souchay in 1842, gluing vent to ocry

of despair provoked by a development

in the history of

music whereby the centuries' old

understanding of music an a

self-evident language had been

increasingly lost and replaced by a

desire for a type of

expression that could be couched in

concrete terms. As the 19th century

pursued its inevitable course, the

argument over the respective merits of

absolute music and programme

music raged with increasing ferocity.

For Mendelssohn, however,

the problem was precisely the opposite

- "and not only with entire speeches,

but also with individual words, since

these, too, seem to me so ambiguous,

so open to misunderstanding in

comparison to actual music, which

fills one's soul with a thousand

better things than words. The thoughts

expressed by the music that I love are

not too vague to be put

into words, but too specific."

And it was Mendelssohn

- a composer who consciously described

several collections of his piano

pieces as ` Songs without Words" - who

achieved an intimate blend of absolute

musical form and poetical idea so

that, far from the one being

sacrificed to the other; they enhance

and enrich one another. In his twelve

early string sinfonias of 1821-1823,

he had, as it were, retraced the various

stages in the development ol the

symphony, beginning with 18th-century

three-movement models and concluding

with the four-movement

type as it had emerged under

Viennese Classicism. In doing so,

he haul not only acquired a sense of

formal assurance through his delight

in experimentation but,

by limiting himself to a complement of

strings, had

created the basis for the translucent

textures of his later orchestral

works. This phase in his development

was brought to an end with his

Symphony in C minor op. 11 of 1824,

the first of his symphonies deemed

worthy of public performance, after

which he turned to writing overtures.

In 1826, while Carl

Maria von Weber was busy staging Oberon,

the seventeen-year-old Mendelssohn

developed a similar enthusiasm for

Shakespeare's spirit world, a world

that had been opened up to the whole

of the German-speaking public through

the translations of Schlegel and

Tieck. Framed by cadential harmonies

on the woodwind, from which the whole

of the musical argument develops, the

overture to A Midsummer Night's

Dream runs its magical course

within the space of a mere twelve

minutes. Different characters and

different levels of the plot are

evoked in graphic themes without ever

losing sight of the underlying musical

idea, an idea firmly

grounded in clearly recognisable

sonata form. “The mature composer

achieved his first and highest flight

of fancy in a moment of suprerne

felicity,” wrote Robert Schumann,

admirably summing up a work of genius

that survived even Mendelssohn's

acute self-criticism when, sixteen

years later, he took up the piece unaltered

and used it as the overture for his

incidental music to the play.

Whereas the overture to A

Midsummer Night's

Dream was written within the

space of only a month, that of The Hebrides

- originally entitled Die einsame

Insel (The Lonely Island)

- took four years to complete. It

was begun in the course of a tour of

the Scottish Highlands, during which

the composer visited Fingal's Cave on

the island of Staffa. He wrote to his

family: “ln order to make clear what a

strange mood has come over me in the Hebrides,

the following occured to me" - and he

went on to note down a 21-bar

orchestral sketch of the overture.

Finally to become known as The Hebrides,

it was still descrrhed in the first

edition of the full score as Fingal's

Cave. “With its basalt

columns reminiscent of organ pipes and

remarkable echo effect, this

cave has two attractions for

tourists," notes Nikolaus Harnoncourt.

"It is by

no means out of the question that

Mendelssohn undertook

the strenuous sea voyage precisely

because of this acoustic phenomenon, a

phenomenon that we can at least ausume

left its mark on the

striking play with the overture’s

dotted woodwind theme".

The sketches accompanied the composer

to Italy and thence to

Paris, from where he wrote to his

sister Fanny: "I can't give The

Hebrides here, since I

don't yet regard it as finished; the

middle section in a loud D major is very

silly." Further revisions followed and

in this form the work was performed in

London in 1832, but

a third version conducted by the

composer himself in Berlin in 1833

- was necessary before Mendelssohn was

satisfied with the result. As before,

the piece is cast in

sonata form, but, unlike the wealth of

images in the overture to A

Midsummer Night's Dream, the

potential for musical conflict derives

on this occasion from the opposition

between a seemingly unassailable

main theme that retains im basic

outline on in countless different

appearances, and melodic forms which,

deriving from it, keep on assuming new

guises

Mendelssohn’s setting of Goethe’s

ballad about the Blocksberg,

Die erste Walpurgisnacht, dates

from 1832. The

overture, which was the final piece to

be written, opens with a description

of winter's passing storms and the

approach of smiling spring

(represented by the clarinet over a

gentle string accompaniment) and looks

forward to the grotesque and comical

action of the ballad itself, which

tells of an ancient

pagan fertility festival. As

before, Mendelssohn was satisfied with

the work only after he had revised it,

and it was not until 1843

that it was heard for the first time

in Leipzig. In the composer's own

words, it appeared “in a somewhat

different guise from before", no

longer "over-dressed with trombones".

Mendelssohn's overture

to The Fair Melusine

dates from 1833

and proved, in its composer`s words,

to be his "best or, at all events,

most inward" overture. He was inspired

to write it by a performance of

Conradin Kreutzer's

opera Melusine that he heard

in Berlin in the spring of 1833: "The

overture was encored, though I

disliked it quite particularly [...].

I was seized by a

desire to write an overture that

people wouldn't encore but that they

would receive more inwardly."

For Nikolaus Harnoncourt, who

is particularly fond of this work, The

Fair Melusine is

an example of "programme music at its

most explicit. With

its five-part strtrcture - Melusine's

theme, the knight's theme, passion,

irreconcilability,

separation - it provides both air

accurate reflection and a wonderful

interpretation of the fairytale". In

this particular version of the tale,

by the Austrian dramatist Franz

Grillparzer, the mermaid Melusine

falls in love with a knight. For his

sake, she enters the world of men,

wins his love and leads a life of

happiness at his side on condition

that he never asks her about her

origins. But the knight's curiosity

finally gets he better of him;

secretly he observes her on the one

day of the week when he is forbidden

to visit her, and it is

then that he sees her fish's

tail and recognises

her for what she is.

Melusine has to return to her watery

realm.

The desire on the part

of a creature such as a nixie, nymph

or undine to be loved

by a human being was a popular

theme among 19th-century artists,

expressing, as it did, the typically

Romantic longing for a horne in the

world and, at the same time, the unbridgeable

gulf between the elemental world and

that of human beings. Fairy-tales of

all ages have served to tell of

existential truths that could not

otherwise be put into words, but this

particular myth of the irreparable

breach in the world is

without any doubt one of the most

moving. In Mendelssohn's

sympathetic setting, even the "Once

upon a time” of the tentative opening

bars expresses man's sense of grief at

the lost unity of humankind and

nature. When these bars are repeated

at the end of the piece, they appear

in a diderent light as a result of all

that has been heard in the meantime.

Once again, Mendelssohn

uses contrastive themes, but on this

occasion the theme symbolising

the ideal harmony that exists among

natural creatures and the brash motif

associated with the world of chivalry

are opposed by a third theme,

entrusted to the oboe, which leaves

its traces in both these worlds,

seeking to effect a rapprochement,

only to abandon them in the end more

lonely than ever before. Whereas

Mendelssoln's concert overtures are

rightly regarded as highly original

works that served as a model for many

later character-pieces and for the

sort of programme music

written by composers ranging from

Berlioz, Schumann and Wagner to Liszt,

Smetana and Tchaikovsky, the merger

between sonata form, overture and

poetic tone-painting that Mendelssohn

first essayed in this

work was to prove of the first

importance for his symphonic writing

in general.

Virtually coeval with the Melusine

overture is the composer's Italian

Symphony, a work which, thanks not

least to the letters that he wrote

from Italy, has

always run the risk of being

misconstrued as a musical Baedeker.

But Mendelssohn was no more concerned

here than he had been in his concert

overtures to indulge in mere

scenepainting, even if in the final

movement, which is headed “Saltarello”

and which recalls the overture to A

Midsummer Night's

Dream, he was inspired

by Neapolitan folk music. Far from

being intimidated by the shade of

Beethoven, he succeeded in clothing

his new ideas in compelling symphonic

garb, ideas whose novelty was by no

means lost on contemporary audiences.

The English conductor Julius

Benedict, who had studied with Carl

Maria von Weber, was one of the first

to point out, in a review

of the piece, that it represented a

radical new departure and that it was

“far ahead of its time".

Ronny

Dietrich

The author is

principal dramaturge at the

Zurich Opera. Both here and

in her previous appointments

at the Alte Oper in

Frankfurt and the Vienna

Konzerthaus, she has an

opportunity to follow

Nikolaus Harnoncourt's

work closely over a period

of many years.

Translation: Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|