|

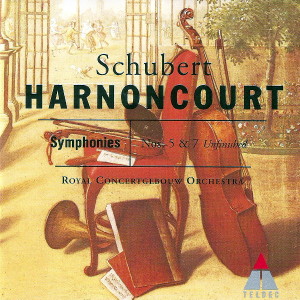

1 CD -

0630-10017-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

| Franz

Schubert (1797-1828) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 5 in B flat

major, D 485 |

|

26' 39" |

|

- Allegro

|

7' 21" |

|

1

|

- Andante con moto

|

8' 46" |

|

2

|

- Menuetto: Allegro molto

|

4' 44" |

|

3

|

- Allegro vivace

|

5' 48" |

|

4

|

| Symphony No. 7 in B minor, D

759 "Unfinished" |

|

26' 22" |

|

| - Allegro moderato |

14' 56" |

|

5

|

- Andante con moto

|

11' 26" |

|

6

|

| Overture in the

Italian Style in D major. D 590 |

|

8' 12" |

7

|

| Overture in the

Italian Style in C major. D 591 |

|

7' 56" |

8

|

|

|

|

|

| Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra |

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Het

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam (Olanda) -

novembre 1992

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

studio

|

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

Teldec

- 4509-91184-2 - (4 cd) - 59' 05" + 68'

57" + 77' 39" + 58' 30" - (p) 1993 - DDD

(Symphonies No. 5 & No. 7)

Teldec - 0630-10017-2 - (1 cd) - 69' 29"

- (p) 1995 - DDD (Ouvertures)

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

Nota

|

La

nostra numerazione delle sinfonie segue

la Neue-Schubert-Gesamtausgabe

(nuova edizione integrale delle opere di

Schubert) e il catalogo delle opere

compilato da Otto Erich Deutsch. Nella

vecchia edizione integrale la Sinfonia

"Incompiuta" era stata catalogata dopo

le prime sette sinfonie compiute come n.

8. In seguito si è dato alla Sinfonia in

do maggiore il n. 9, con l'intenzione di

ordinare cronologicamente

l'"Incompiuta", ai frammenti della

Sinfonia in mi (D 729) è stato pertanto

attribiuto il n. 7.

|

|

|

A Clash

Between Art and Life

|

When Nikolaus

Harnoncourt's complete recording of

Schubert's symphonies with the Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra was released

in 1993, the world of music was

brought face to face with a wholly new

approach to Schubert's scores, an

approach which, with its unprecedented

expressivity and wide dynamic range,

entailed a radical revision of

existing views of Schubert as a

quintessentially undramatic and

invariably lyrical composer. While

preparing for a performance of

Schubert's Fourth Symphony,

Harnoncourt examined the autograph

score in Vienna and discovered that

this and Schubert's other holograph

scores contain countless corrections

made by Brahms and his team of

editors. The symphonies had neter been

performed in public during Schubert's

lifetime and the autograph scores had

fallen into neglect following his

death. It was not until the 1880s that

Brahms brought out his edition of all

the composer's symphonies, an edition

on which the majority of modern

performances continue to be based. "If

you compare them with Schubert's

manuscript,” Harnoncourt explains,

"you’Il find a whole host of changes

to the dynamics, tempi, articulation

markings, instrumentation and even the

notes themselves. with entire bars

deleted or added. These far-reaching

editorial changes were clearly aimed

at making these inspired works by an

allegedly incompetent composer

playable and enjoyable. The prevailing

mentality - no doubt due to the best

of intentions - was that of a caring

governess who finds that her child is

very talented but that its work needs

improving. There is a clear attempt to

adapt these symphonies to the taste of

the second half of the 19th century.”

Since there is no performing tradition

dating back to Schubert's own time.

Harnoncourt had to study the sources

in detail in order to reconstruct

these symphonies in accordance with

their composer's intentions.

The first six symphonies were written

between 1813 and 1818 and, in contrast

to the later works, are regularly seen

as more or less successful attempts to

perpetuate the symphonic tradition of

Mozart and Beethoven. For Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, however, there is no

difference between the earlier and

later works of a composer who died at

the age of thirty-one: "Franz Schubert

was a born composer. He was a natural.

All his teachers testified that there

was nothing more they could teach him.

There is no doubt that he acquired his

knowledge of the great works of Haydn,

Mozart and Beethoven largely by

studying contemporary scores, but from

the outset he composed with total

independence. Every one of his

surviving works is unmistakably pure

Schubert. They all reflect a frame of

mind, an attempt to come to terms with

death. I know of no other composer who

has tried so honestly to come to terms

with this particular aspect of life

and who saw the tragedy of the world

against the background of his ovm

private destiny, but who never

composed autobiographically."

A comparison between the two

symphonies included here illustrates

Harnoncourt's point. Both works

revolve around the same ideas, which

could be described in the most general

terms as the clash between art and

life, between a desired ideal and

reality. Lyrical outpourings are

forever offset by oppressive tragedy.

The same language is spoken in both

works, even if, in his Fifth Symphony,

Schubert restricts himself to a small

orchestra with single flute, two

oboes, two bassoons and two horns,

whereas the orchestra of the

“Unfinished” also includes clarinets,

trumpets, trombones and timpani, The pianissimo

chord that opens the B flat major

Symphony corresponds with the unisono

motif on the lower strings at the

start of the B minor Symphony, a motif

that gains in importance in the

subsequent course of the movement. The

world of harsh reality that repeatedly

intrudes upon the opening movements of

both these works is largely excluded

from the second movement of the Fifth,

an Andante con moto in 6/8 time that

is lullaby-like in character; with an

intimacy that brooks no interruption.

It is significant that in the third

movement of this symphony Schubert

contrasts two themes from his opera Der

Teufels Lustschloß, which he had

revised and completed only a short

time previously. Whereas the Menuetto

is based on a theme associated with

the allegedly haunted castle of the

title (“Scarce one hundred paces from

this tavern stands an old ruined

castle"), the Trio answers with a song

sung by the servant Robert, "Why

should I care about marshy land, why

should I care about the weather?", the

third verse of which contains the

lines, "We stumble over many stones on

our journey through life, everyone

suffers his own torment and complains

in his own way", with a modulation to

the minor in the orchestral

accompaniment.

The Fifth Symphony was written in

1816. Earlier that same year, Schubert

had noted in his diary in the context

of Mozart's music: "Thus does our soul

retain these fair impressions, which

neither time nor circumstances can

efface and which lighten our

existence. They show us in the

darkness of this life a bright, clear

lovely distance, in which we can

confidently place our hopes." These

words may be applied unreservedly to

Schubert's own works, particularly to

the second movement of his

"Unfinished" Symphony of 1822, the

motifs and themes of which open our

eyes to a beauty that is not of this

world and with which the symphony dies

away, beyond all sense of rebellion,

The extent to which Schubert remains

unmistakably himself at every moment

of his creative life is clear from his

two overtures "in the italian style",

which were written in quick succession

at the end of 1817. They were intended

as an antidote to the Rossini fever

that gripped Vienna at this time, a

fever which, to the dismay not only of

Schubert but also of Beethoven, caused

all other music to be forgotten. Even

if Schubert permitted himself the joke

of quoting the most popular of

Rossini’s tunes, "Di tanti palpiti"

from Tancredi, in the middle

section of his D major Overture, both

works succeed, in spite of their

superficial frivolity, in conveying a

highly individual message. "You can

try playing Schubert like Rossini, and

people have tried to do so, especially

in the contemporary Sixth Symphony."

Harnoncourt explains, “but if Schubert

was inspired by this Rossini madness,

the inspiration he received from this

quarter was completely transformed,

for the simple reason that the two

composers are diametrical opposites.

There is no tragedy in Rossini,

whereaa in Schubert there is only

tragedy. If Schubert took over

superficial forms, it was to invest

them with a wholly new meaning."

Ronny

Dietrich

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|