|

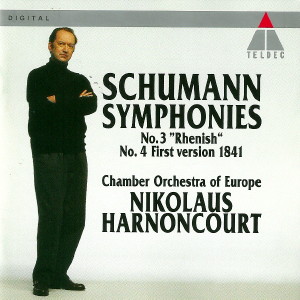

1 CD -

4509-90867-2 - (p) 1994

|

|

| Robert

Schumann (1810-1856) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 3 in E flat

major, Op. 97 "Rhenish" |

|

32' 20" |

|

| - Lebhaft |

10' 13" |

|

1

|

| - Scherzo: Sehr mäßig |

6' 09" |

|

2

|

- Nicht schnell

|

5' 14" |

|

3

|

| - Feierlich |

4' 51" |

|

4

|

| - Lebhaft |

5' 53" |

|

5

|

| Symphony No. 4 in D minor,

Op. 120 - First

version 1841 |

|

24' 09" |

|

- Andante con moto - Allegro

di molto

|

8' 43" |

|

6

|

- Romanza:

Andante

|

3' 17" |

|

7

|

- Scherzo: Presto [Largo]

|

6' 17" |

|

8

|

- Finale: Allegro vivace

|

5' 52" |

|

9

|

|

|

|

|

| Chamber

Orchestra of Europe |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Stefaniensaal,

Graz (Austria):

- giugno 1993 (Symphony No. 3)

- luglio 1994 (Symphony No. 4) |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 4509-90867-2 - (1 cd) - 56' 35" - (p)

1994 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Giving berathing-space to

Schumann's genius

|

As with so many other

composers, Nikolaus Harnoncourt

has found the key to

interpreting Schumann's music in

a detailed study of the

autograph scores, as well as in

the composer's letters and other

contemporary documents. Simple

though this approach may sound,

Harnoncourt's method none the

less has radical implications

for his interpretation of the

works in question. Margarete

Zander visited Harnoncourt

while he was preparing for

performances of the Third and Fourth Symphonies and discovered a new

Schumann.

Once the layers of dust that have

accumulated over the years have been

swept away; the works of every

genius stand revealed in their most

iridescent colours. Particularly exciting

in this respect is the rediscovery

of the l84l version of the Fourth

Symphony (chronologically speaking,

Schumann's second completed symphony). Its first

performance passed largely

unnoticed, overshadowed as it was by

other works and by

the joint presence on the concert

platform of Franz Liszt and Clara

Schumann, with the result that no

publisher could be found to take on

a work that failed to attract any

further interest. It

was in order to carve a niche for

the symphony in the concert hall

that Schumann set about revising it

ten years later.

Clara Schumann declined to include

the first version in her husband's

official work-list,

refusing to be swayed even hy the

advocacy of so eloquent a champion

as Johannes Brahms, who wrote to

her: “Far more valuable to me is my

ownership of the first version of

the D minor Symphony. Everyone who

sees it agrees with me that the

score has not gained by being

revised and that it has undoubtedly

lost much of its charm, lightness of

touch and clarity of expression."Harnoncourt is fond

of quoting these lines and, like

Brahms, regards the two symphonies

as independent works. In

his view the first version is

particularly well suited to a

chamber orchestra such as the

Chamber Orchestra of Europe: “The

first version differs frorn the

second in its chamber-like style, its

sirnpler, more transparent

instrumentation and its more spontaneous

ternpi.” The second

version (which Brahms described as

"over-dressed") is

differently instrumented, has newly

written bridge passages and is

notable for

its doublings in the wind

department.

Harnoncourt is

currently more fascinated, however,

by the first version

of what Schumann himself described

as a "one-movement symphony”: "At

the moment of composition each idea

is entirely original. At the time

when Schumann was writing this

symphony - and he wrote very quickly

- he lived and breathed the ideas

involved, ideas inseparable from his

biorhythms and from his spontaneous

feelings at that time. It was evidently at

the desire of his friends or perhaps

merely at the desire of his wife,

Clara, that he took out the work

again ten years later and revised

it. The spontaneity and idea were no

longer there: what we have instead

are composed motives which, as far

as Schumann was concerned, already

belonged to the past. He had to

approach these things from without.

its a revision of his own work, so

to speak. This says nothing about

the quality: I find the second

version no less wonderful than the

first, but it's

essentially a different work,

precisely because Schumann

approached the symphony from the outside. He altered

a lot of details

that he certainly didn't want to be

any different the first time round,

since he'd lived and breathed every

bar of the piece,

as you can hear. The first version

is that of the inventor at the

moment of invention."

Harnoncourt studied

a synoptic edition of the two

symphonies that had formerly been

owned by Brahms, a study that

deepened his awareness of the differences between

the two versions. Schumann's many

corrections and deletions,

especially when writing out the

Fourth Symphony, made it difficult

to decipher the autograph score. On

completing this task, Harnoncourt

remarked: "I`ve

tried to distil something like a

first version from the autograph,

which is full of corrections.

Whether it’s really the first

version, as Schumann wanted, one can't of course say -

but we've not played a single note

that isn’t in the full score of the

first version."

Harnoncourt is convinced that

“Schumann wrote with tremendous

speed and intensity. He began by

sketching on two staves, since he

simply couldn't write as fast as he

was thinking. In other words, he

wanted to capture as many of his

ideas as possible and create an

architectural structure - a single arching

paragraph - over

the work as a whole, before sitting

down in peace and quiet and

elaborating the sketch in the form

of a full score. The speed is

amazing." Harnoncourt describes

Schumann's instrumentation as

“uniqne’: “Schumann was a born

orchestral composer, perfect instrumentation came

easily to him. Almost all other

composers have had to struggle to find the right

choice of instruments and have

composed at the piano. Schumann did

this to perfection on the basis of

instinct, talent and his own innate

abilities. Far too often the

opposite has been claimed."

These observations concerning the

creative process and Schumann's

instrumentation have revolutionary

repercussions. For a long time

musicologists and critics have cast

doubt on Schumamn's abilities, as

listed by Harnoncourt: the

composer's genius was lost in a mass

of musicological rules, whose criteria could

not do justice to

Schumann's works. Harnoncourt gives

breathingspace to Schumann's genius.

In the Third Symphony, too,

Harnoucourt does not have to

transfer the emotional intensity of

the fourth (interpolated) movement

to the remaining movements. He

emphasizes the flowing, ländler-like rhythms,

the harmonic writing in the inner

parts, the spirited finale and the

piece’s much-discussed Rhenish

character. From its lively first

subject to its folksong-like finale,

the Third

Symphony contains biographical

features. In 1850 Schumann had taken

up a new appointment as director of

music in Düsseldorf,

an appointment that seemed to fill

him with hope and optimism.

In the course of his

rehearsals with the orchestra, Harnoncourt paints a vivid

picture of Schumann’s new

surroundings and tells the players

about the Rheinland and its people.

He describes the

atmosphere of a great celebration in

Cologne Cathedral. The fourth

movement, which turns the work into

a five-movement symphony, is said to

have been written with the memory of

the archbishop's recent elevation to

the College of Cardinal's still

fresh in Schumann's mind and is

distinctively majestic in tone.

Listeners to the present CD will

perhaps be struck by the unusual

seating arrangement of the

orchestra. Harnoncourt

was anxious to reproduce the sort of

seating arrangement that was usual

in Schumann's day, although it was

also important that the players

should feel comfortable.

Harnoncourt has

nothing but admiration for

Schumann's genius. In answer to the

question whether Schumann - who initially

could not decide whether to become a

writer or a composer - had in fact become

a composer-poet, Harnoncourt

replies: "If we’re going to make

comparisons with a different form

of expression from music, I'd be inclined to

speak in Schumann's

case of painting rather than

language."

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|