|

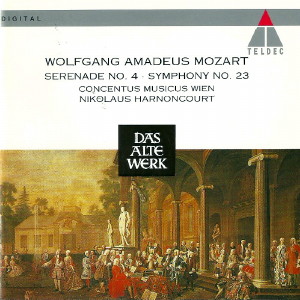

1 CD -

4509-90842-2 - (p) 1994

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Serenade No. 4 in D major |

|

|

|

| Marcia, KV

237 (189c) |

|

3' 49" |

1

|

| Serenade,

KV 203 (189b) |

|

46' 40" |

|

| - Andante

maestoso |

8' 56" |

|

2

|

| - Andante |

5' 21" |

|

3

|

| - Menuetto

- Trio |

3' 55" |

|

4

|

| - Allegro |

5' 18" |

|

5

|

| - Menuetto - Trio |

3' 54" |

|

6

|

| - Andante |

9' 28" |

|

7

|

- Menuetto

- Trio

|

4' 27" |

|

8

|

| - Prestissimo - Coda |

5' 21" |

|

9

|

| Symphony No. 23 in D

major, KV 181 (162b) |

|

9' 31" |

|

| - Allegro spiritoso

- Andantino grazioso - Presto assai |

9' 31" |

|

10

|

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

-

Erich Höbarth, Violine

|

-

Dorle Sommer, Viola |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine |

-

Gerold Klaus, Viola |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

-

Ursula Kortschak, Viola |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violine |

-

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violine |

-

Max Engel, Violoncello |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Violone |

|

| -

Maighread McCrann, Violine |

-

Robert Wolf, Querflöte |

|

| -

Christina Busch, Violine |

-

Reinhard Czasch, Querflöte |

|

| -

Editha Fetz, Violine |

-

Hans Peter Westermann, Oboe |

|

| -

Maria Kubizek, Violine |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe |

|

| -

Irene Troi, Violine |

-

Christian Beuse, Fagott |

|

| -

Herlinde Schaller, Violine |

-

Andrew Joy, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Christian Tachezi, Violine |

-

Rainer Jurkiewiez, Naturhorn |

|

| -

Thomas Feodoroff, Violine |

-

Andreas Lackner, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter junior, Violine |

-

Martin Rabl, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Lynn Pascher, Viola |

-

Dieter Seiler, Pauken |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

Casino

Zögernitz, Vienna (Austria) - dicembre 1992

|

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann /

Stefan Witzel

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 4509-90842-2 - (1 cd)

- 60' 37" - (p) 1994 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

It was not until 1831

that Friedrich Rochlitz, writing in

the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung,

first signalled the existence of what

he described as "three volumes of

original manuscripts by

W. A. Mozart"

in the possession of the Hamburg

music-publisher August Cranz. All

three volumes were small in size and

bound in blue-grey

cloth. The first of them contained

nine symphonies, the second a

concertone (K. 190) and

three serenades (K. 203, 204 and 250),

and the third only a single serenade

(K. 185) and a march (K.

189). Although the dates

entered at the start of each work have

all been rendered illegible by an

unknown hand, we know that it was only

after his return from his third visit

to Italy, in March 1773, that Mozart

began using this small landscape

format. In other words, the works in question

must have been written either in 1773

or later and were presumably, for the

most part, the result of commissions

from ltalian, Milanese

or Lombardic

patrons.

The D major Symphony K. 181 is written

in the manner of an italian-style

overture and might have been intended

for an opera, an idea that receives

support not only from the fact that

the three movements are joined

together without a break

but more especially from the musical

language of the work, a language

which, to a degree that even today

continues to elicit amazement, seems

to suggest a kind of action of

altogether theatrical immediacy. It

is surely significant in this context

that the not yet seventeen-year-old

composer had been in Milan at the end

of 1772 to prepare for the first

performance of his opera Lucio

Silla. Equally "theatrical" are

the instrumental forces deployed, with

two oboes, two horns

and two trumpets in addition to the

usual complement of strings.

Motivically, tonally and dynamically,

too, the listener is inevitably

reminded of an opera when

following the three movements of this

overture-like

symphony. Or was Mozart simply in an

impish mood? Was he wanting, above all

else, to set his listeners thinking?

Perhaps there is irony waiting to be

discovered here, too, an irony that

has ensured that so idiosyncratically

distinctive a symphony has been

practically ignored in the world of

music.

Certainly, one cannot help being

struck by the way that tremolo

passages in the strings over triadic

figures in the bass can create the

feeling of chords, that G minor chords

and the interplay between major and

minor still have the power to shock,

and that there is a notable absence of

any thematic writing in the sense of a

clear melodic line. The diminished

seventh makes as though to announce

something that subsequently fails to

materialize. What we hear is a number

of syncopated effects, octave leaps

and imitative entries creating a sense

of momentum, but nothing else. Nor is

there a ”second” subject, lout,

instead, a dialogue between strings

and wind, a feature that attests to

Mozart's unique ability to operate

beyond strict rules, to avoid all that

is expected and, as the composer

Wolfgang Rihm once said of him, ”never

to do anything really ’properly':

everything is somehow wrong, which is

why this music still lives for us

today".

It was for precisely this reason,

however, that Mozart's music was able

to give rise to misunderstandings,

even in 1826. Thus, for example, we

read in Hans Georg Nägeli's Vorlesungen über Musik mit Berücksichtigung

des Dillettanten (Lectures on Music

with Due Regard to the Amateur)

of this year: "Tender

melodies frequently alternate with

harsh, abrasive sounds, charm of

movement with violence. Great was Mozart’s

genius, but equally great was his

erroneous wish to create his effects

through contrast, a failing typical of

genius in general and all the more

deplorable in that he constantly

contrasted the non-instrumental with

the instrumental, cantabile writing

with a freer style. It

was inartistic, as it is in all the

arts when something has to achieve its

effect through its polar opposite. It

had a distorting effect, first and

foremost on himself, because as soon

as perpetual contrast is raised to the

level of a general principle, one

loses sight of the beautiful sense of

proportion that exists between the

individual parts of any work of art."

Mozart was clearly

experimenting in the opening movement

of K. 181, just as, thanks to his use

of a characteristic timbral device

involving a trill, he hesitates,

rhythmically and gesturally, between a

"quick march” and what Saint-Foix

termed a "quick step” in the final

movement. In the middle movement he

gives the solo oboe an opportunity to

perform a regular operatic aria.

Timbre is briefly emphasized in the

final movement, when Mozart suddenly

demands divided violas for eight bars.

Like the D major Symphony K.

181, the Serenade in D major K.

203 has clear operatic associations,

as Alfred Einstein has already pointed

out: ”The built-in violin concerto,

this time in B flat major and in three

instead of only two movements, is now

fully formed, a true work within a

work, not a mere episode.

One thinks involuntarily of a similar

process in the history of opera: the

inclusion of an opera buffa or

intermezzo between the acts of an opera

seria. In the opening movement

of the concerto there is another

remarkable pointer to the future: the

contrast between the main melody and

the garrulous interjections on oboes

and violas, and that between Donna

Anna and Don Ottavio on the one hand

and Donna Elvira and Don Giovanni on

the other in the B flat major quartet

- even the key is the same.” In short,

we have further proof here of the

theatrical aspect of Mozart's

thinking as an instrumental composer.

Mozart added a

manuscript note to the autograph of

the Serenade: "Serenata del Sgr.

Wolfgango Amadeo Mozart, nel mese

d’agosto 1774”. Here, too, the year

was later deleted, although there is

no reason to doubt the accuracy of the

attribution. Mozart's

first biographer, Franz Xaver

Niemetschek, argued that it was

written for the name day of the

Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg

Hieronymus Colloredo but although the

work continues to this day to bear the

nickname ”Colloredo Serenade”, it

seems unlikely that the work was in

fact written on this occasion. To

judge by the seriousness of its

extended movements and the strictness

of the thematico-motivic

writing, one is tempted to think that

Mozart must have had a more important

reason for composing it. Here, too,

there are contrasts of a dramatic

nature. A weighty slow introductory

section of symphonic significance is

contrasted with sparkling fast

movements unclouded

in character. An Andante reveals

itself as another evocation of an

operatic aria, but we also hear

distinctively Mozartian rninuet-like

rhythms and fleeting notturno-like

musings. Since Mozart was an

outstandingly good violinist, it seems

likely that it was with himself in

mind that he wrote the violin concerto

incorporated in this serenade.

At the time that

Mozart wrote the D major Serenade, it

was usual practice, at least in the

case of open-air performances, for the

players to march into position and,

at the end of the performance, to

march away again. Mozart

is believed to have written such a

march to introduce and round off the D

major Serenade, too. Since there are

thematic links

between serenade and march, it has

been assumed that both works were

intended as a single entity, but the

fact that the march is not scored for

violas and that it demands two bassoons,

instead of the single bassoon required

in the serenade, might

tend to favour the argument of those

scholars who insist that the march is

not, after all, part of the serenade.

Be that as it may, the march might

still function as a prologue and

epilogue and, given its compositional

density, would also

ensure the right note of

portentousness.

Wolf-Eberhard

von Lewinski

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|