|

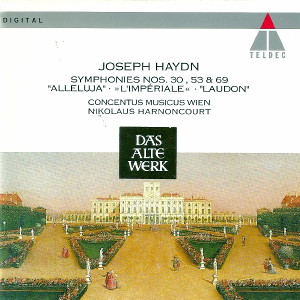

1 CD -

9031-76460-2 - (p) 1992

|

|

| Franz Joseph

Haydn (1732-1809) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 30 in C major,

Hob. I/30 "Alleluja" |

|

14' 55" |

|

| - Allegro |

5' 02" |

|

1

|

- Andante

|

5' 24" |

|

2

|

- Finale: Tempo di Menuet,

più tosto Allegretto

|

4' 29" |

|

3

|

Symphony

No. 53 in D major, Hob. I/53

"L'Impériale"

|

|

25' 46" |

|

- Largo maestoso - Vivace

|

11' 11" |

|

4

|

| - Andante |

6' 23" |

|

5

|

| - Menuetto - Trio |

3' 42" |

|

6

|

| - Finale. Capriccio Moderato

(Version A) |

4' 27" |

|

7

|

| Symphony

No. 69 in C major, Hob. I/69 "Laudon" |

|

25' 29" |

|

- Allegro vivace

|

6' 18" |

|

8

|

- Un poco Adagio, più tosto

Andante

|

11' 28" |

|

9

|

| - Minuetto - Trio |

3' 53" |

|

10

|

- Finale. Presto

|

3' 45" |

|

11

|

|

|

|

|

| Concentus

Musicus Wien |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Casino

Zögernitz, Vienna (Austria) - 12-14

giugno 1990 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut A. Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 9031-76460-2 - (1 cd)

- 66' 37" - (p) 1992 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

In a

letter written in 1810

Goethe asked the composer Zelter:

”Please inform me as soon as possible

what songs are most frequently sung in

your group, so that I

may acquaint myself with the taste of

your guests and what sort of poetry

they most enjoy. If

one knows that one can provide all

sorts of entertainment for one’s

friends.”

Right up to the early 19th century

there was no irreconcilable conflict

between an artist’s striving for

popularity and his creative

self-fulfilment. Thus many of the

symphonies which Haydn wrote during

thirty years in the service of Prince

Nicolaus Esterházy in

the Hungarian countryside provided

what his princely patron expected to

hear. They were also unlikely to have

disturbed the customary conversation

and card games at concerts.

Symphony No. 30, however, clearly

indicates that Haydn, in spite of the

pleasing nature of his music, was also

concerned to compose something more

than mere background music. It

may have been intended for

performance on Easter Sunday 1765,

since the first movement is based on

nn Alleluia that formed part of the Mass

for Easter Week. Attentive listeners

who had not missed the service would

certainly have recognized it. Incidentally,

this Alleluia was very popular as a

basis for compositions:

Mozart later wrote a canon on it and

Prince Esterházy may

well have been fond of it, because

Haydn used it again in a trio for his

employer’s favourite instrument, the

barytone. In Haydn's

symphony it is initially hidden away

in one of the accompanying parts,

but then it appears again -

in a varied form - in

the main parts. Finally it is played,

loudly and unmistakably, even by any

card players, in the wind instruments.

The delicate solo passage for flute

and oboes in the following movements

will certainly not have escaped the

now wideawake audience.

In an autobiographical sketch dating

from 1776 Haydn drew up a balance

sheet of his activities ”with His

Highness the Prince... with whom I

wish to live and die". He named as

his most successful works three

operas, an oratorio and the Stabat

mater. There are brief

references to his chamber music, but

not a word about his symphonies.

Prince Esterházy's

declining interest in symphonies in

the middle of the 1770's

was probably due to the excessive

demands which they made. Haydn's

immediately preceding so-called “Sturm

und Drang” phase must have been too

complicated for him. Certainly the

symphonies were thereafter

significantly simpler. They are once

again in the major,

instead of being in unconventional

minor keys; complex

thematic work, which assumes a certain

amount of concentration, is replaced

by cheerful, simpler themes.

Particular effects are mainly harmonic

and therefore easily observable.

This did not, incidentally, detract in

any way from the popularity of

Symphony No. 53. On the contrary, it

was one of his most successful

compositions and copies of it were

available all over Europe. Harmonic

effects, characteristic of Haydn’s

symphonic style at that time, are to

be found in the first movement, with

its exciting return to the main theme,

and the Minuet. Here a repeat of the

theme is marked by a dissonance

instead of the expected final chord,

leading to a charming chromatic

passage, and only then is the

”correct” conclusion arrived at. The

theme of the Andante, a set of

variations, was one of Haydn's

best-loved melodies. It was

immortalized as early as 1793 on the

Haydn memorial which his admirers had

erected in his birthplace Rohrau.

There are several final movements of

Symphony No. 53. Because

at that time the demand at Esterháza

was above all for operas, Haydn used

in one version an opera overture

composed in 1777. In France there

appeared a final movement which was

certainly not by Haydn.

The finale recorded here may not have

been by Haydn himself, but is

undoubtedly a product of his circle;

according to the Haydn scholar Robbins

Landon it may have been written by a

pupil under the master’s supervision.

In the 18th century

attributions of this kind were

regarded as a compliment to the great

name and are further evidence of his

popularity.

Exceptionally the nickname of Symphony

No. 69, "Laudon”, was coined by Haydn

himself and refers to its dedication

to the Austrian Field Marshal, Baron

von Laudon or Loudon. Having defeated

Frederick II of

Prussia at the battle of Kunersdorf

and captured Belgrade in one of the

Turkish Wars, he was extremely

popular. Thus Haydn justified an

incomplete arrangement of the symphony

in a letter to his publisher Artaria

with the words: ”Meanwhile

I am sending your

Honour the symphony, which is so full

of mislakes that the

hand of the fellow who wrote

it ought to be chopped off;

the last or fourth part of this

symphony cannot he played on the

piano, and I don’t

consider it necessary to include it;

the word Laudon will contribute more

to promoting sales than ten

finales.”

Considered from a musical point of

view (and in its orchestral version)

the finale is both possible to play

and essential. The earlier movements

have found no particular favour with

Haydn scholars; they are thought to

be emotionally low-key and rather

conventional. This is the very reason

for suspecting that they may have

reflected rather too closely General

Laudon’s taste. But

the finale, with its sudden dynamic

alternations, its vvild passage in the

minor and the entirely unexpectedly

soft violin solo leading up to the

return of the main theme, forms a

triumphal conclusion

to the Symphony.

Marie-Agnes

Dittrich

Translation: Gery

Bramall

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|