|

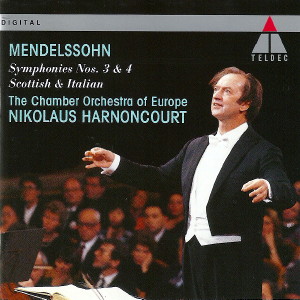

1 CD -

9031-72308-2 - (p) 1992

|

|

| Felix

Mendelssohn (1809-1847) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 3 in A minor,

Op. 56 "Scottish" |

|

39' 46" |

|

| - Andante

con moto - Allegro un poco agitato |

16' 21" |

|

1

|

| - Vivace non troppo |

4' 17" |

|

2

|

| - Adagio |

9' 16" |

|

3

|

- Allegro

vivacissimo - Allegro maestoso assai

|

9' 52" |

|

4

|

| Symphony No. 4 in A major,

Op. 90 "Italian" |

|

28' 44" |

|

- Allegro vivace

|

10' 35" |

|

5

|

- Andante con moto

|

6' 42" |

|

6

|

- Con moto moderato

|

5' 49" |

|

7

|

- Saltarello: Presto

|

5' 38" |

|

8

|

|

|

|

|

| The Chamber

Orchestra of Europe |

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Teatro

Comunale, Ferrara (Italia) - ottobre

1991 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 9031-72308-2 - (1 cd) - 69' 05" - (p)

1992 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

In 1842

Robert Schumann made a mistake which

was as delightful as it was

significant. He was

reviewing Mendelssohn's new symphony,

which he thought was the "Italian”

because...

... thus may the

imagination of the master well have

been assailed

by fond recollections

when he found these old melodies

sung in beauhful Italy among his

papers, finally resulting,

consciously or unconsciously, in

this tender tone painting.

What Schumann thought

of as the reflection of Italy is,

however, the idiom of the “Scottish”.

Even an expert can be deceived.

Schumanns mistake is significant

in so far as there is confusion

between these two symphonies even

concerning their numbering; the

“Italian” was completed in l833, The

“Scottish”

in 1842;

chronologically, therefore, it was the

4th Symphony.

In 1830

Mendelssohn set off on an

eighteen month long trip to Italy,

taking with him to Rome the

sketches for his “Scottish” Symphony.

It was entirely in

keeping with contemporary practice, as

represented by Goethe or Jean Paul,

that Mendelssohn should prepare a

musical account of his travels; the

"Italian" was also sketched under

southern skies. Seen from the

viewpoint of their origins, the

two symphonies are closely linked;

nevertheless it is worthwhile

enquiring into the

specifically

"Scottish" or “Italian”

idiom, in other words, to

track down the hidden

programmes which the two

symphonies appear to follow in their

different ways. The answers are

contradictory, because it suited the

romantic conception of art carefully

to encode personal experiences,

impressions, recollections and

inspirations, that is to

say to disguise them as

mysterious puzzles.

First of all

the “Scottish” context. In

1829 Mendelssohn wrote

from Edinburgh:

This evening, in the deep twilight,

we went to the palace where

Queen Mary lived and

loved;

there is a small room with a

winding staircase leading to

the door (...).

The adjacent chapel has lost its roof; grass

and ivy grow thickly within; and

on the

broken altar

Mary Was crowned

Queen of Scotland. Everything there

is in ruins and ramshackle, open to the blue sky.

I think

I have

today

found the

opening of my Scottish Symphony.

Landscape, historical

personages and their warfare

- Mendelssohn seems to

have absorbed these atmospheric

impressions, especially in the

elegiac mood of the

inlroduction, and

presumably also in the

tone-painting

of a storm scene at

the end of the

first movement. History

as the

history of warfare is also implied in

the fourth movement:

Mendelssohn suggested

calling it "Allegro

Guerriero", which is apprapriate

because the extensive

warlike complexity is

followed by a kind of "song

of thanks-giving

after victory

in battle". The composer

had very precise ideas on how this

should sound; he envisaged the

hymn of thanksgiving as

sounding like an instrumental

"male voice choir". In

1842 he wrote

to F.

David:

If the melody

still does not come out

clearly, let the

horns in D play louder.

And if

even that does

not help, I

hereby formally authorize you

to

omit the

three drum rolls in the first 8 bars (...). I

hope that

this

will not

be necessary and that it now sounds

distinct and firm, lika a male voice

choir.

Mendelssohn obviously also had a clear

conception of the

landscape. In a letter

from Rome dated

29th March 1831

he wrote;

The loveliest time of the year in Italy

is the period from 15th April to 15th May:

- who then

can blame me for not being

able to return to the mists of

Scotland? This is why I have

had to put aside the symphony

for the time being.

So it

was to

be the misty

landscape of Scotland.

We encounter il not

only in the opening and

closing bars of the first

movement, but

also in the darkened,

melancholy melodic line of the

Adagio movement, the

opening theme of which

is pentatonic

and undoubtedly based

upon a naïve Scottish

folk tune. This

movement may also be

described as folkloric

on accounl of the way

in which it joins

together similar

individual dances into

an unbroken series. Popular simplicity

thus finds expression

in formal simplicity.

The “Italian”

context is more difficulf

to discover. It

is only in the final

“Saltarello” (which

Wulf Konold in 1987 more appropriately

called “Tarantella”) that

it is completely

out in the

open, particularly as Mendelssohn

wrote in a letter

from his travels on 1st

March 1831:

If only I could get

to grips with one of the

two symphonies! I will and must

save the Italian up until I have

seen Naples, because that must be

involved.

Naples is indeed involved in the

fourth movement.

And in the others? In

1974 Martin

Witte linked Mendelssohn's

experiences in Italy -

his experience of classical harmony in

architecture

and the fine

arts - with

the

neo-classical perfection

of this

“classical symphony". In

1988 Karl Heinrich

Ehrenforth expressed the

view that

Mendelssohn was impressed with the

religious processions in Rome, and that

this explains the

processional character

of the slow

movement. Eric

Werner, on the other

hand, drew attention in

1963 to

the almost literal

correspondence between the

theme of the

Andante and Zelter’s

setting of Goethe’s "Es

war ein König in Thule",

making this movement

a tribute to

two distinguished

friends of Mendelssohn, who had both

died in 1832. This

suggests another

interpretation: the

freshness and verve of the

first movement

and the exuberant

dance mood of the southern

Saltarello would,

according to this

view, provide a contrast

with Mendelssohn's own nordic temperament

(represented by the

seriousness of the Goethe/Zelter

song), reflecting the

composer's experience of being an outsider,

a stranger in a strange

environment. And the

slow movement

reveals something else: the

unbroken stream of

quavers might even

represent a symbol of the

inexorability of

passing time; but

its inescapability

is exorcised by the

finite ballad theme,

in wich the song, a

self-contained entity,

represents an

element of the

present in the

all-devouring flow of time.

Art dares to raise an utopian

objection to the

inevitable.

Ehrenforth even goes

a step further and

conjectures:

This interpretation of the second

movement can be biographically confirmed. The

great

monuments of Rome and Naples overwhelm

the visitor

to Italy with their

historical impact, reducing his own

short life span

sub specie

aeternitatis

to a single breath. This is brought home to

him most vividly when

confronted

by the

then still unrestored city of

Pompeii, still very largely buried

beneath

the ash which rained down from

Vesuvius. On 27th April 1831 - after his visit

to Pompeii -

Mendelssohn writes under the influence

of this experience of the "tragedy

of pasf and present, which will be

with me for as long as I live”.

But that would

be more than a mere

musical account of his

travels, it would be a form of

existential

introspection, an unexpected profundity

behind this apparently gay and carefree musical

façade. The

question what is actually “Scottish”

or “Italian”

in Mendelssohn's music must,

therefore, remain unanswered.

And Schumann’s mistake is. in the

cold light of day, even more comprehensible.

Hans

Christian

Schmidt

Translation: Gery

Bramall

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|