|

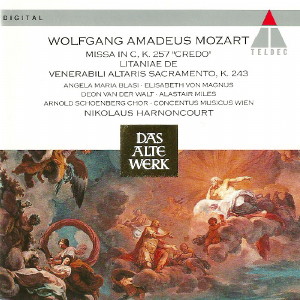

1 CD -

9031-72304-2 - (p) 1992

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Missa C major, KV 257 "Credo"

|

|

24' 54" |

|

| - Kyrie |

2' 13" |

|

1

|

| - Gloria |

3' 15" |

|

2

|

| - Credo |

8' 08" |

|

3

|

| - Sanctus |

1' 19" |

|

4

|

| -

Benedictus |

4' 31" |

|

5

|

| - agnus Dei

- Dona nobis |

5' 28" |

|

6

|

| Litaniae

de venerabili altaris sacramento, KV 243 |

|

35' 58" |

|

| - Kyrie |

3' 05" |

|

7

|

| - Panis

vivus |

4' 57" |

|

8

|

| - Verbum

caro factum |

1' 21" |

|

9

|

| - Hostia

sancta |

4' 27" |

|

10

|

| - Tremendum |

3' 21" |

|

11

|

| - Dulcissimum convivium |

4' 26" |

|

12

|

| - Viaticum |

2' 07" |

|

13

|

| - Pignus |

5' 49" |

|

14

|

| - Agnus Dei - Miserere |

6' 25" |

|

15

|

|

|

|

|

| "Missa

Credo" |

"Litaniae" |

|

|

|

|

| Angela Maria

Blasi, Sopran |

Angela

Maria Blasi, Sopran

|

|

| Elisabeth von

Magnus, Alt |

Elisabeth

von Magnus, Alt |

|

| Deon van der Walt,

Tenor |

Deon

van der Walt, Tenor |

|

| Alastair Miles,

Baß |

Alastair

Miles, Baß |

|

|

|

|

| Arnold Schönberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Einstudierung |

Arnold

Schönberg Chor / Erwin Ortner,

Einstudierung |

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

CONCENTUS

MUSICUS WIEN (mit

Originalinstrumenten)

|

|

-

Erich Höbarth, Violine

|

-

Erich Höbarth, Violine |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine |

-

Alice Harnoncourt, Violine |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

-

Anita Mitterer, Violine |

|

| -

Andrea Bischof, Violine |

-

Andrea Bischof, Violine |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

-

Peter Schoberwalter, Violine |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violine |

-

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violine |

-

Helmut Mitter, Violine |

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine |

-

Walter Pfeiffer, Violine |

|

| -

Silvia Walch, Violine |

-

Silvia Walch, Violine |

|

| -

Maighread McCrann, Violine |

-

Maighread McCrann, Violine |

|

| -

Annemarie Ortner, Violine |

-

Annemarie Ortner, Violine |

|

| -

Mary Utiger, Violine |

-

Mary Utiger, Violine |

|

| -

Edith Fetz, Violine |

-

Edith Fetz, Violine |

|

| -

Gerold Klaus, Violine |

-

Gerold Klaus, Violine |

|

| -

Christian Tachezi, Violine |

-

Christian Tachezi, Violine |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter junior, Violine |

-

Peter Schoberwalter junior, Violine |

|

| -

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

-

Kurt Theiner, Viola |

|

| -

Dorothea Guschlbauer, Violoncello |

-

Johannes Flieder, Viola |

|

| -

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

-

Lynn Pascher, Viola |

|

| -

Andrew Ackerman, Violone |

-

Charlotte Geselbracht, Viola |

|

| -

Hans Peter Westermann, Oboe |

-

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

|

| -

Marie Wolf, Oboe |

-

Dorothea Guschlbauer, Violoncello |

|

| -

Trudy van der Wulp, Fagott |

-

Eduard Hruza, Violone |

|

| -

Christian Beuse, Fagott |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Violone |

|

| -

Friedemann Immer, Naturtrompete |

-

Robert Wolf, Traverflöte |

|

| -

Andreas Lackner, Naturtrompete |

-

Sylvie Sumereder, Traverflöte |

|

| -

Martin Kerschbaum, Pauken |

-

Hans Peter Westermann, Oboe |

|

| -

Ernst Hoffmann, Posaune |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe |

|

| -

Josef Ritt, Posaune |

-

Trudy van der Wulp, Fagott |

|

| -

Horst Küblböck, Posaune |

-

Christian Beuse, Fagott |

|

| -

Herbert Tachezi, Orgel |

-

Hector McDonald, Naturhorn |

|

|

-

Alois Schlor, Naturhorn |

|

|

-

Ernst Hoffmann, Posaune |

|

|

-

Josef Ritt, Posaune |

|

|

-

Horst Küblböck, Posaune |

|

|

-

Herbert Tachezi, Orgel |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Leitung |

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Pfarrkirche,

Stainz (Austria) - luglio

1991 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Renate

Kupfer / Wolfgang Mohr / Helmut Mühler /

Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

"Das Alte Werk" - 9031-72304-2 - (1 cd)

- 61' 28" - (p) 1992 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart paid a visit to the Leipzig

Thomaskirche in l789. During his visit

there he had occasion to speak with

the Cantor of St. Thomas, Johann

Sebastian Bach’s pupil Friedrich

Doles, an encounter we know of from

Doles. (Friedrich Rochlitz, Authentische

Anekdoten aus Wolfgang Gottlieb

Mozart's

Leben; AMZ 1800/1801, p. 494)

Speaking as a Roman Catholic, Mozart

voiced his concern about Doles'

Protestant perception of the

Mass: “You do not sense at all the

sentiment of Agnus Dei, qui

tollis peccata mundi, dona nobis pacem

and passages of the like... but as for

me, initiated from earliest childhood

in the mystic holiness of

our religion, when I

knew not where to turn with my

shrouded yet ardent impulse to believe

- without so much as a

clue as to why that feeling was there

- when I found myself in anxious and

heartfelt anticipation of worshipping

in church and then parted the service

uplifted and relieved in spirit, yet

not knowing what I

had just partaken

of, when I knew those

who knelt down to the moving sound of

the Agnus Dei for Holy Communion to be

joyful, and upon receiving Communion

heard how the music expressed their

heartfelt ioy with the words

Benedictus qui

venit etc.; to me then there is a

difference." Mozart himself admitted

to having lost a fair amount of this

childlike happiness and trust in God

by virtue of worldly experiences. What

remained was Mozart's thankfully

received experience of God ”as the key

to our true contentment." (Letter of

April 4, 1787 to his

father)

It is of course not imperative that a

consideration of Mozart’s sacred

compositions also take

his personal faith into account. His

sacred settings are in their own right

primarily works of art with inherent

dictates of their own. Even

so, any attempt to shed light on the

question of Mozart's religious nature

will also add valuable insight to

one’s understanding of his Masses, Litanies

and other church compositions.

Mozart’s childhood had after all been

spent in the sovereign diocese of

Salzburg which maintained close ties

with the archiepiscopal court.

Attending church was an understood

everyday rite in any young person’s

life. The abundance of sacred music

played and sung within the sumptuous

confines of Salzburg Cathedral was to

be a mainstay in forming his musical

taste. Mozart was able to take the bravissimo

contrapunctista Cajetan

Adlgasser, Michael Haydn and not least

of all his own father and rnenton

Leopold Mozart, as models in the

development of his church style. The

further experience Mozart was able to

gain by hearing glorious sacred

settings during three trips to Italy,

the musical ”Promised Land," also left

deep impressions on him.

The majority of Mozart’s liturgical

compositions stem from his duties as

Concertmaster at Salzburg's

archiepiscopal court starting in

November of 1769. Even if it is true

that Hieronyrnus Graf von

Colloredo-Waldsee, installed as

Archbishop of Salzburg in 177l,

felt that service music needed to

serve the rational and functional

ideas of the Age of Reason - a view

far different from that held by his

predecessor Archbishop Sigismund Graf

von Schrattenbach who was enamored of

pomp and splendour in service music -

Masses were nevertheless scored "with

all instruments, with trumpets and

timpani.” Mozart reports to Padre

Martini on September 4, 1776

that a mass was not to exceed three

quarters of an hour in length. Mozart

greeted this imposed limitation with

scorn but rose to the occasion as

well, composing six Masses from March

1775 to September

l777.

Among the six was the C Major Mass, K.

257, known as the Great Credo Mass,

as oppossed to the Small Credo

Mass, K. 192. The

title refers to the extended Credo

movement which forms a culminating juncture

within the Mass: Christ becomes Man

and His Crucifixion. The motif given

to the word “Credo” consists of four

tones which become what H. Abert calls

a “liturgical motto,” emphatically

recurring eighteen times.

Mozart research does well to mark a

turning point in his settings of the

Ordinary with the Credo Mass,

K. 257. There appears to be no extant

work which served as a model for this

composition. Mozart blithely

transgresses formal boundaries,

combining aspects known

to him from the symphonic, operatic

and concerto form while not forgetting

the prototype ot the traditional

Salzburg Mass. The art of counterpoint

plays a lesser role while at the same

time taking on "new meaning” (A.

Einstein). Mozart also seeks new

avenues when shaping the melodic line,

crafting simple and profoundly

expressive personal statements. Ho

also assigns three trombones to the

instrumental complement for the first

time. As it was, this practice had

been generally understood - an

unwritten law, so to speak - in

Salzburg for quite some

time. The brevity called for

by Colloredo required

other formal solutions: this would be

the explanation for the almost total

lack of repeat signs and, with the

exception of the Agnus Dei,

the reason why all movements are

through-composed. The

Mass, first performed in Salzburg in

November of 1776,

exists in autograph, “copied with

utmost care and beauty" (W. Plath).

On Palm Sunday of the

same year the Litaniae de

veneiabili altaris sacramento,

K. 243, could be heard in the Salzburg

Cathedral. It has been the practice

since early Christian times to sing a

sacramental litany during the

Eucharist. Southern German and

Austrian areas displayed a

predilection for songs of praise or

prayers of supplication with recurring

acclamations of

”rniserere nobis” ("Have

mercy on us"). Mozart relied on the

multiple movement cantata form he had

become acquainted with while in Italy

to formalize his setting

of the Ordinary for divine-service.

And once again he was faced

with considerable formal problems for

which he devised ingenious solutions -

the antiphonal exchange between

the choir and solo voices, the highly

dramatic, virtuoso coloratura arias, Panis

vivus and Pignus

(Movements 2 and 8), and notably the

thematic coupling of the opening Kyrie

and the closing Agnus Dei. The

amount of thematic material assigned

to the instruments is also worthy of

note. Numerous instruments are given

concertizing parts on equal footing

with the vocal parts. The symphonist

in Mozart makes itself evident not

only in the contrasting thematic

material and finely

differentiated dynamic shadings,

but also in the orchestral timbre and

cunning harmonic modulations.

Even if the conversation between

Mozart and Doles never did take

place at the Thomaskirche in Leipzig,

both settings of the Ordinary, K. 243

and K. 257, make clear how deeply

moving these "words heard a thousand

times over” were to Mozart.

Ingeborg

Allihn

Translation:

Matthew Harris

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|