|

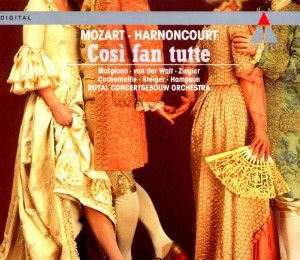

3 CD -

9031-71381-2 - (p) 1991

|

|

Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Così fan tutte, ossia La

scuola degli amanti, KV 588 |

|

|

|

| Dramma giocoso in due atti -

Libretto: Lorenzo da Ponte |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ouvertura |

|

4' 11" |

CD1-1 |

Atto Primo

|

|

91' 25" |

|

| - No. 1 Terzetto: "La mia

Dorabella" - (Ferrando, Don Alfonso,

Guilelmo) |

1' 59"

|

|

CD1-2 |

| - Recitativo: "Fuor la spada" -

(Ferrando, Don Alfonso, Guilelmo) |

1' 13" |

|

CD1-3 |

| - No. 2 Terzetto: "E' la fede

delle femmine" - (Ferrando, Don Alfonso,

Guilelmo) |

1' 06" |

|

CD1-4 |

| - Recitativo: "Scioccherie di

poeti!" - (Ferrando, Don Alfonso,

Guilelmo) |

1' 39" |

|

CD1-5 |

| - No. 3 Terzetto: "Una bella

serenata" - (Ferrando, Don Alfonso,

Guilelmo) |

2' 24" |

|

CD1-6 |

| - No. 4 Duetto: "Ah, guarda,

sorella" - (Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

4' 35" |

|

CD1-7 |

| - Recitativo: "Mi par, che

stamattina" - (Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

1' 19" |

|

CD1-8 |

| - No. 5 Aria: "Vorrei dir, e cor

non ho" - (Don Alfonso) |

0' 33" |

|

CD1-9 |

| - Recitativo: "Stelle! Per

carità" - (Fiordiligi, Dorabella, Don

Alfonso) |

1' 08" |

|

CD1-10 |

| - No. 6 Quintetto: "Sento, oh

Dio" - (Guilelmo, Ferrando, Don Alfonso,

Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

4' 32" |

|

CD1-11 |

| - Recitativo: "Non piangere,

idol mio!" - (Guilelmo, Ferrando, Don

Alfonso, Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

1' 06" |

|

CD1-12 |

| - No. 7 Duettino: "Al fato dàn

legge" - (Ferrando, Guilelmo) |

1' 42" |

|

CD1-13 |

| - Recitativo: "La commedia è

graziosa" - (Don Alfonso, Ferrando,

Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

0' 31" |

|

CD1-14 |

| - No. 8 Coro: "Bella vita

militar!" - (Coro) |

1' 24" |

|

CD1-15 |

| - Recitativo: "Non v'è più

tempo" - (Don Alfonso, Fiordiligi,

Dorabella, Ferrando, Guilelmo) |

0' 38" |

|

CD1-16 |

| - "Muoio d'affanno!" - No. 8a

Recitativo: "Di scrivermi ogni giorno" -

(Fiordiligi, Dorabella | Guilelmo,

Ferrando, Don Alfonso) |

3' 02" |

|

CD1-17 |

| - No. 9 Coro: "Bella vita

militar!" - (Coro) |

0' 45" |

|

CD1-18 |

| - Recitativo: "Dove son?" -

(Dorabella, Don Alfonso, Fiordiligi) |

0' 59" |

|

CD1-19 |

| - No. 10 Terzettino: "Soave sia

il vento" - (Fiordiligi, Dorabella, Don

Alfonso) |

2' 19" |

|

CD1-20 |

| - Recitativo: "Non son cattivo

comico!" - (Don Alfonso) |

1' 20" |

|

CD1-21 |

| - Recitativo: "Che vita

maledetta" - (Despina) |

1' 12" |

|

CD1-22 |

| - Accompagnato: "Ah, scostati" -

(Dorabella) |

1' 03" |

|

CD1-23 |

| - No. 11 Aria: "Smanie

implacabili" - (Dorabella) |

1' 41" |

|

CD1-24 |

| - Recitativo: "Signora

Dorabella" - (Despina, Dorabella,

Fiordiligi) |

2' 23" |

|

CD1-25 |

| - No. 12 Aria: "In uomini! In

soldati" - (Despina) |

2' 55" |

|

CD1-26 |

| - Recitativo: "Che silenzio!" -

(Don Alfonso, Despina) |

2' 59" |

|

CD1-27 |

| - No. 13 Sestetto: "Alla bella

Despinetta" - (Don Alfonso, Ferrando,

Guilelmo, Despina, Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

4' 37" |

|

CD1-28 |

| - Recitativo: "Che sussurro!" -

(Don Alfonso, Dorabella, Fiordiligi,

Ferrando, Guilelmo, Despina) |

2' 33" |

|

CD1-29 |

| - Accompagnato: "Temerari!

Sortite!" - (Fiordiligi) |

1' 17" |

|

CD1-30 |

| - No. 14 Aria: "Come scoglio" -

(Fiordiligi) |

4' 19" |

|

CD1-31 |

| - Recitativo: "Ah non partite!"

- (Ferrando, Guilelmo, Don Alfonso,

Dorabella, Fiordiligi) |

1' 12" |

|

CD2-1 |

| - No. 15 Aria: "Non siate

ritrosi" - (Guilelmo) |

2' 06" |

|

CD2-2 |

| - No. 16 Terzetto: "E voi

ridete?" - (Ferrando, Guilelmo, Don

Alfonso) |

1' 03" |

|

CD2-3 |

| - Recitativo: "Si può sapere" -

(Don Alfonso, Guilelmo, Ferrando) |

1' 05" |

|

CD2-4 |

| - No. 17 Aria: "Un'aura amorosa"

- (Ferrando) |

4' 48" |

|

CD2-5 |

| - Recitativo: "Oh la saria da

ridere" - (Don Alfonso, Despina) |

2' 46" |

|

CD2-6 |

| - No. 18 Finale: "Ah che tutta

in un momento" - (Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

18' 56" |

|

|

CD2-7 |

| - "Si mora, sì, si mora" -

(Ferrando, Guilelmo, Don Alfonso,

Fiordiligi, Dorabella, Despina) |

|

|

| - "Eccovi il medico" - (Don

Alfonso, Ferrando, Guilelmo, Despina,

Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

|

|

| - "Dove son?" - (Ferrando,

Guilelmo, Despina, Don Alfonso,

Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

|

|

Atto

Secondo

|

|

99' 58" |

|

| - Recitativo: "Andate là" -

(Despina, Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

3' 45" |

|

CD2-8 |

| - No. 19 Aria: "Una donna a

quindici anni" - (Despina) |

3' 43" |

|

CD2-9 |

| - Recitativo: "Sorella, cosa

dici?" - (Fiordiligi, Dorabella) |

1' 51" |

|

CD2-10 |

| - No. 20 Duetto: "Prenderò quel

brunettino" - (Dorabella, Fiordiligi) |

3' 02" |

|

CD2-11 |

| - Recitativo: "Ah correte al

giardino" - (Don Alfonso, Dorabella) |

0' 23" |

|

CD2-12 |

| - No. 21 Duetto con Coro:

"Secondate, aurette amiche" - (Ferrando,

Guilelmo, Coro) |

3' 10" |

|

CD2-13 |

| - Recitativo: "Il tutto

deponete" - (Don Alfonso, Fiordiligi,

Dorabella, Despina, Ferrando, Guilelmo) |

1' 04" |

|

CD2-14 |

| - No. 22 Quartetto: "La mano a

me date" - (Don Alfonso, Ferrando,

Guilelmo, Despina) |

2' 42" |

|

CD2-15 |

| - Recitativo: "Oh che bella

giornata!" - (Fiordiligi, Ferrando,

Dorabella, Guilelmo) |

3' 26" |

|

CD2-16 |

| - No. 23 Duetto: "Il core vi

dono" - (Guilelmo, Dorabella) |

5' 03" |

|

CD2-17 |

| - Accompagnato: "Barbara! Perchè

fuggi?" - (Ferrando, Fiordiligi) |

1' 47" |

|

CD2-18 |

| - No. 24 Aria: "Ah, lo veggio" -

(Ferrando) |

4' 42" |

|

CD2-19 |

| - Accompagnato: "Ei parte ...

senti!" - (Fiordiligi) |

1' 30" |

|

CD2-20 |

| - No. 25 Rondo: "Per pietà, ben

mio, perdona" - (Fiordiligi) |

8' 33" |

|

CD2-21 |

| - Recitativo: "Amico, abbiamo

vinto!" - (Ferrando, Guilelmo) |

4' 38" |

|

CD3-1 |

| - No. 26 Aria: "Donne mie, la

fate a tanti" - (Guilelmo) |

4' 42" |

|

CD3-2 |

| - Accompagnato: "In qual fiero

contrasto" - (Ferrando) |

1' 40" |

|

CD3-3 |

| - No. 27 Cavatina: "Tradito,

schernito" - (Ferrando) |

2' 12" |

|

CD3-4 |

| - Recitativo: "Bravo: questa è

costanza" - (Don Alfonso, Ferrando,

Guilelmo) |

1' 33" |

|

CD3-5 |

| - Recitativo: "Ora vedo che

siete" - (Despina, Dorabella, Fiordiligi) |

2' 57" |

|

CD3-6 |

| - No. 28 Aria: "E' amore un

ladroncello" - (Dorabella) |

3' 26" |

|

CD3-7 |

| - Recitativo: "Come tutto

congiura" - (Fiordiligi, Guilelmo,

Despina, Don Alfonso) |

3' 02" |

|

CD3-8 |

| - No. 29 Duetto: "Fra gli

amplessi" - (Fiordiligi, Ferrando) |

6' 04" |

|

CD3-9 |

| - Recitativo: "Ah poveretto me!"

- (Guilelmo, Don Alfonso, Ferrando) |

2' 25" |

|

CD3-10 |

| - No. 30 Andante: "Tutti accusan

le donne" - (Don Alfonso, Guilelmo,

Ferrando) |

1' 09" |

|

CD3-11 |

| - Recitativo: "Vittoria,

padroncini!" - (Despina, Ferrando,

Guilelmo, Don Alfonso) |

0' 40" |

|

CD3-12 |

| - No. 31 Finale: "Fate presto" -

(Despina, Don Alfonso, Coro) |

21' 28" |

|

|

CD3-13 |

| - "Benedetti i doppi coniugi" -

(Fiordiligi, Dorabella, Ferrando,

Guilelmo, Coro) |

|

|

| - "Miei signori, tutto è fatto"

- (Don Alfonso, Fiordiligi, Dorabella,

Ferrando, Guilelmo, Despina, Coro) |

|

|

| - "Sani e salvi, agli amplessi

amorosi" - (Ferrando, Guilelmo, Don

Alfonso, Fiordiligi, Dorabella, Despina) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Charlotte

Margiono, Fiordiligi, Dama

Ferrarese sorella di Dorabella

|

|

| Delores Ziegler,

Dorabella, Dama Ferrarese sorella

di Fiordiligi |

|

| Gilles

Cachemaille, Guilelmo, amante

delle sorelle |

|

Deon van der Walt,

Ferrando, amante

delle sorelle

|

|

| Anna Steiger,

Despina,

cameriera |

|

| Thomas Hampson,

Don Alfonso,

vecchio Filosofo |

|

|

|

| Continuo: Glen

Wilson, Harpsichord / Wim

Strasser, Violoncello |

|

| De Nederlandse

Opera Chorus / Winfried

Maczewski, Chorus Master |

|

| ROYAL

CONCERTGEBOUW ORCHESTRA AMSTERDAM |

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent |

|

|

Luogo e data

di registrazione

|

| Concertgebouw, Amsterdam

(Olanda) - gennaio 1991 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer / Engineer

|

| Wolfgang Mohr / Renate Kupfer

/ Helmut Mühle / Michael Brammann |

Prima Edizione

CD

|

Teldec - 9031-71381-2 - (3 cd)

- 63' 40" + 76' 52" + 56' 02" - (p) 1991

- DDD

|

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

The School of Love or

the Confusion of Emotions

|

Problems of

Listening to Mozart

Pandelea: You once called Mozart a

Romantic

compaser. Could you explain this

classification

which,

at first

glance, seems somewhat bewildering?

Harnoncourt: Actually

I would not describe Mozart in general

as a Romantic composer. But certain of

his vvorks and certain sounds I

do feel to be romantic, and I

also believe that from an historical

point of view this is

not wrong, because

the idea of romanticism comes from

literature and was

already present in Mozart's generation.

Some authorities on literature take

the view that Romanticism begins with

“Wilhelm Meister” or with “Werther”

and I agree with

that.

I find, for example,

many romantic elements in Mozart's

first mature opera “Idomeneo”

- in his attitude to

nature and in the orchestration. And

remarkably enough it is precisely the

combination of horns

and clarinets which creates a very tender

and romantic sound - although of

course "romantic" is not

an accepted term tor a sound. It

is the manner and the situations in

which Mozart uses these sounds that I

call romantic. That is why, soon after

Mozart's death, the

symphonies which were

written for the classical combination

of wind instruments (two oboes and two

horns) were played with clarinets

instead of oboes, because the

Romantics considered

the sound of the

oboes to be too obvious and too

direct, not mysterious enough.

Clarinets were better at

expressing mystery, which was very

important for romanticism.

There is a very good example of this in

“Così fan tutte”. In

the first three numbers, when the men

are discussing the constancy of their

women, we have a concrete,

mundane scene in an interior and this

is set for the standard orchestra Then

the scene changes to the garden by the

sea, where the women are enthusing

over the pictures of their absent

lovers or fiancés.

It ought really to strike every

listener that the sound of this first

entry, before the women

begin to sing, is completely new. This

is a very old trick (which to my knowledge

Monteverdi used right

at the beginning of

the l7th century) of setting the stage

with sound, to create, so to speak,

tonal scenery. The ladies, who are out

in the open rather than indoors,

are placed in the context of nature

and a feeling of mystery Mozart

achieves this with the entry at the

clarinets and horns. That is what

I meant by "romantic".

It is also the case

that, for example, many turns of

phrase which we describe as

“Schubertian” are first found in

Mozart. But in Mozart's case, it is

one of a thousand phrases and one

marvels; "Ah, Mozart is already

writing like Schubert.” - But that is

only because we know Schubert. Somehow

or other the roots of this highly

romantic musical language that

Schubert employed 20 years after

Mozart’s death is already present in

Mozart.

We know

fairly precisely how Mozart himself

did not want to be played. But do we

also know just as precisely how he

did want to be performed?

I believe that, being unable to ask

him, we shall never know that. When we

consider the history of penormances

over the last 200 years, we can see

that virtually every generation has

tried to perform and understand Mozart

as he would have wanted it. And each

generation has corrected the previous

one and said that they did it all

wrong. I believe that this really is

the case and that it will happen to us

in exactly the some way.

It may sound funny to

talk about fashion, but music has many

parallels with fashion; what is

enjoyed and thought correct today will

be laughed at in a few decades’ time.

This happens today when Mozart

interpretations recorded, say, in 1908

are played to contemporary “experts”

One can recognise clearly what the

performers were trying to achieve, and

that they performed with great love

and great professionalism. I

marvel at their technical mastery,

which is often superb. I

would immediately engage some of the

singers on these records, just because

they are so good.But

they do things which, when played to a

wider forum of experts, make people

laugh. I think this

is most unfair. It also

makes me realise that what we

are doing today will, after an

appropriate interval, let us say of 80

years, certainly reduce people to

laughter. I

believe we recognise the mistakes made

by the musicians who immediately

preceded us and we do not repeat them.

We make new mistakes.

Mozart is simply so great that he can

stand up to every re-examination of

his compositions. We

believe that we know more than our

predecessors. We

believe that we have a closer

understanding of his markings. We

believe that we have a

feeling for his musical language. But,

measured against the total rightness

of the work, what we do can only be to

shine some sort of searchlight on a

single point. I once used

the comparison of a beetle or an ant

crawling about on a hill. That's what

we are, Mozart being the hill. We

could only get the really correct

interpretation if we stood at two

metres distance from this hill and saw

the whole hill. That would represent

the totality of the work,

that would be everything. (Maybe that

is how Mozart performed his own

works.) If we crawl

about on this hill, all we can see

lies in a radius of a few centimetres;

that is all we can recognise, and we

neglect everything else.

Of course this means

that the next person who comes along

crawls around in a different place and

illuminates something else. Of course

nothing is more important to me than

to understand as much as possible of

what the composer is trying to say. I

believe that the love that a performer

brings to the composer's works is also

a means by which he can appreciate as

much as possible of what he is trying

to say.

It is also still an

open question whether it is really all

that wrong to go along with fashions

in music. It may

well be that if we were to do

everything absolutely correctly we

might not be able to communicate with

people who have no feeling for the

earlier period. The way

people hear today is completely different

from 200 years ago and perhaps they

understand the essence of the music

much better if it is performed with objective

faults. There are many sides to this

question.

Language and truth in “Così fan tutte”

The first act

of “Così” is often thought of as

joyful, almost boisterous, the

second as sad. You yourself once

said that “Così” is the

saddest opera in the history of

music. Is

that true?

Yes, I still think

that. But I don't

see this division between Acts One and

Two. I think the socalled Farewell

Quintet, which Mozart did not call a

Quintet but a Recitative, is one of

the saddest pieces that I

know. That is one of

the moments in which one realises what

Mozart was getting at in "Così".

The two girls are devastated because

their fiancés have

got to go away, but the men know that

it is all just

playacting. They sing a quartet in

which they just stammer the first

thing that enters their minds: “Please

write to me every day and don't forget

me.” The verbal high point is the word

“Addio” that they say

to one another. There is no

distinction between those who mean

what they say and those who are

playing a part. (The only one who says

what he feels is Don Alfonso,

who is speaking as an outsider and is

laughing at the

insiders on what one might call quite

a different level.) Evidently Mozart

stepped completely into the shoes of

his characters: at that moment not

even the young men are lying, because

their own words of farewell really

make them feel that it is a farewell.

I believe that the

repercussion of speech on the speaker

is one of the more profound levels of

the background to the piece.

Present-day psychology is familiar

with the situation in which a sad

person becomes cheerful by speaking

cheerful words and a cheerful person

becomes sad by speaking sad words.

That something becomes true because it

has been uttered. There are things

that ought not to be said, because

they can never be unsaid.

In the foreground of

this piece is the declaration of love.

Each of the young men declares his

love to the other’s fianéee,

without meaning it while they say it.

But one cannot use language

like that without paying the price. If

you say three or four times to someone

“I love you", then the

phrase “I love you"

becomes so powerful that you and the

other person are transformed merely by

that phrase. For that reason it is not

only playing with fire,

but the destruction of feeling.

One of the things which I

find extraordinarily fascinating is

that every word which has been set to

music means a little bit more than if

it were merely spoken. There are often

in fact two or three texts which can

be heard at the sametime.

An example is the tenor aria “Un aura

omorosa” before the Finale to Act One.

Anyone hearing this aria hears a great

Love Aria. Guilelmo's text which

precedes it, however, is “And don't we

get anything to eat

today?" No doubt people laughed

because the young men were simply

talking about eating. Ferrando

answers: "What is the point? After the

battle dinner will taste all the

better.” And after this joke about

eating he sings: “The loving breath of

those we adore will give our hearts

sweet restoration. A heart which is

strengthened by love’s

expectations of better refreshment

then has no more need.” Just looking

at the text by itself, this could have

been turned into a joke on the lines of

"there's nothing to eat except air".

Making it into a declaration of love

to his real fiancée, as

early as the middle of the opera, is

surely a very ambiguous affair. What

is sung and what is spoken here are

not one and the same thing. What is

sung is love and what is spoken is

really just a joke ...

Or let us take as another example the

Trio "Soave sia il Vento".

The text reads: “May the

wind... respond with kindness to our

desires.” lf I read

it or perform it in a play it means:

"Let there be no shipwreck, let the

ship not sink and let the wind bring

them back again as soon as possible.”

But the text does not know that Mozart

is writing a totally dissonant,

magical harmony on the word “desires",

which tells an entirely different

story. The listener hears a big, truly

magical discord which says: there is

something not quite right with our

wishes. But it gives no details.

The girls want their fiancés

to return - But something happens,

there will be something, perhaps they

will came back changed or perhaps...

Perhaps in the next two hours we shall

be terribly deceived in our wishes.

This magical harmony may also mean:

perhaps we don't wish what we wish. At

the moment there is no way of telling.

But there is this "second text" like a

devil behind an angel, both speaking

the same words but meaning something

entirely different.

I believe that one

should not interpret with prior

knowledge of the work. This opera is

written for people who hear it for the

first time. If I

already know what is going to happen

and how it is going to be worked out

musically, my interpretation is too

far-reaching. Mozart uses none of the

old forms in the traditional manner,

but always adds something which brings

it up to date. Fiordiligi’s aria “Come

scoglio”, for

example, could never, as it stands,

have been part ot an earlier opera. (It

is often called “baroque”.)

An essential feature of a baroque aria

is that the singer’s words are

reinforced by the music; thus we have

the Revenge Aria, the Love Aria etc.

But for me “Come scoglio" is a perfect

example of the music saying the

opposite of what the singer is

singing.

First of all we are shown the rock.

Fiordiligi says: "Come scoglio immota

resta" - as the rock remains unmoved,

thus stands my faithfulness.

The listener is reassured up to a

point. There is nothing that can

change a faithful heart. And then

there is the shock of the storm which

arises in the orchestra. This is no

mere question mark; in the musical

vocabulary this is a catastrophe.

Everybody knew what it meant: this is

where the rock collapses. And in the

very moment when it is toppled she

says: “Just as the rock remains

immovable." Musically there is no

longer any question of "immovable",

the rock has already fallen. None of

those taking part notice anything.

Only the listener notices it: “She who

speaks most convincingly about her

faithfulness is already doomed." This

aria makes a terrific impression on

Ferrando, he hears for the first

time how Fiordiligi reacts to a

declaration of love. He can never have

heard anything like that from Dorabella.

He probably falls in love with

Fiordiligi at this point and realises

"I may have chosen the

wrong one". He sees a woman who rebuffs

every suitor. His Dorabella

is certainly quite different.

But what this aria communicates to the

audience is: a magnificent woman, but

already doomed.

Who exactly

is Don

Alfonso? Is

he something like a puppeteer from

the commedia

dell’arte?

There are six characters in this

opera, and I can sympathise with any

one of them or I can be hostile

towards any one of them, according to

my personal tastes. I can say that

Alfonso is a terrible fellow, he is a

cynic, he is a wrecker.

Therefore he is more than just

a puppeteer. His

wager is a terrible game.

One feels that something very fine in

the friendship of these

four young people is being put at

risk.

In terms of Mozart's

age he is certainly a philosopher of

the Enlightenment who does not believe

in eternal values, who has personally

been very disappointed and turns that

disappointment into cynicism. But once

again that is almost too much

interpretation One could see him in a

different light without a single word

or a single note being altered One

might also see htm as someone who

wants to open men's eyes and stop them

going blindly through life.

I don't see him in

that way. In my view he is a cynic and

I have no sympathy for him. I can, however

understand listeners who find Don

Alfonso very sensible and very

sympathetic and say: people wallow in

their unhappiness as long as they are

ignorant. That is an entirely feasible

interpretation. And one can say the

same about virtually every single

character. I can

get cross at Guilelmo and say: ha is a

very vain ladies' man and when he is affected

personally he is pathetically

full of self pity.

And one can do the same with each

individual character...

I can find nothing

negative about Ferrando, who is very

sensitive and very sentimental.

The fact that he

seduces Ithe fiancée of

his best friend by lying to her

is not exactly

an attractive trait.

But with wonderful music. Mozart

always gives him the most

romantic, the most

beautiful, the most

tender, the most expressive arias.

The Duet between Guilelmo and

Dorabella is the only true love duet

in the whole opera.

Even though they have not yet

discovered their love, it is

already a love duet from the

very beginning. It is

most strange that precisely

this couple -I might

almost put it in inverted

commas, the "light-hearted” Dorabella

and the “frivolous” Guilelmo,

who boasts of his

success with women - should suddenly

sing a love duet. The Duet

between Ferrando and

Fiordligi, on the

other hand, ist no

love duet but represents a process

which leads from mutual fear

and very strong mutual rejection to “I

cannot help it” and to their

coming together.

That is Fiordiligi's doing; she is

the most uncompromising of the four

of them. Right until the end

there appears to her to be only one

course.

I suppose you could say that.

The characters are really like

ordinary people. Those who love them

like them and those who do not love

them dislike them. And I could, if I

wanted to, also stand on its head the

accepted view of

Fiordillgi and Dorabelia - that

Fiordiligi is the steadfast one and

Dorabella the

frivolous one. Neither Mozart nor Da

Ponte commit themselves ta their

characterisation of the parts. They

commit themselves in the moment when

each character speaks. But usually the

music contains another text, which

puts in question what is being said.

It is as though we were meeting living

people of whom we can never be quite

certain. One cannot look into other

peoples souls, everyone is a secret to

others. However sympathetic we may

find them, it is possible that they

will be responsible for

the most terrible disappointment. That

possibility always exists,

particularly with the characters in

"Così fan tutte”.

Nothing is actually said, nothing is

cut and dried, they are real, pathetic

human beings. There are no heroes in

this work.

How

irreparable is the smash-up in the

end?

In the context ot what I said just

now, it can certainly be viewed in

very different ways.

And how do you see if?

I regard it as totally irreparable. I

think that the cynical element in Don

Alfonso, who cannot bear

to see happiness around him, is given

great prominence by Mozart. And I

cannot imagine any of

the four people involved having an

innocent relationship with any new

partner - nor with the old partner. I

can well imagine that they will return

to their previous partners and will

live together like a crafty old

married couple, without illusions and

without the innocence of their earlier

relationship. But their ideals are

gone. I see dreadful sadness in this.

I also see

sadness in the fact that betrayal

can co-exist

so closely with love.

Of course. And this contrived cheerful

ending, the excitement at the end,

makes it seem all the more ironic - as

it they were philosophising about the

future.

I do not think that we have yet

mentioned Despina. Her

role provides some particularly fine

examples of the way in

which the music can supplement the

text. One is struck by the fact

that her two arias are real Austrian folk

music. This tells me, just

as it probably told the original

public, that she was from the country,

as were most servants, perhaps from

this or that particular village where

this music was played. The imitation

of rustic instruments such as the

hurdy-gurdy

and the bagpipes is obvious, as is the

use of the waltz, which at that time

was only danced by people of the

lowest class.

Realism in “Così fan tutte”

Although “Così” is considered the

most arificial of Mozart's operas, I

also consider it to be one

of the most

realistic. Is “Così” perhaps

the opera in which Mozart reveals most about himselt?

It is the most realistic in the sense

that the characters are portrayed as

having many different facets.

Mozart can only depict people as he

knew them, as he saw them. Here there

are six many-sided characters, six

people who have totally fluctuating

personalities. Each of them has

mankind's puzzling characteristic: basically

one never knows how they are going to

react to the next situation. Evidently

this genuine spontaneity is achieved

by the way in which Mozart identities

with the character on whom he is

working at any

particular moment. After “Così

fan tutte” one feels one knows more

about Mozart, because he has had to

tell us so much about himself when he

describes each individual character,

and yet at the same time one knows

absolutely nothing. One just

cannot get hold ot Mozart’s character.

White he is writing an aria for

Guilelmo, he is Guilelmo;

he can make him neither more

nor tess sympathetic, because he is

not constructing him from without but

from within.

That is one of the

reasons, in my view, why there are no

truly unsyrnpathetic characters in the

Da Ponte operas. If

you read the text of “Don Giovanni",

you would gladly kill

the protagonist and say: that rnan is

the greatest scoundrel

and criminal evcr.

But if you hear “Don Giovanni”, as un

opera, he wins the sympathy of

the

audience. That can only be because the

composer - perhaps subconsciously

- has identified with this character

and hirnself says what the

character says. To this

extent I believe that one can never

comprehend Mozart as a

person. He is always concealed behind

his characters.

Why did "Così" initially have so

little success in comparison with

Mozart's other operas, particularly

the Da Ponte operas? Can the public not cope with

things like lies, deception and

irony?

“Così” does

not follow the normal pattern of

a play or an opera. Here there is no

hero, no character with whom one can

identify. Normally the public likes to

bestow its sympathy on someone. That

is fine in "Figaro" with Figaro and

Susanna, and it is alsi quite clear in

"Don Giovanni". The

hero is certainly a scoundrel,

but people somehow find him

fascinating. In

"Così" there is no

leading role, but an interplay ot six

characters who all lay their cards on

the table.

The idea of performing

something like that was new at that

time. And one can understand that it

had no great success with a wider

public. I consider the

piece basically moral, in the sense

that it makes people think and makes

them better. There is no question of

evil being overcome by good. Everyone

who has seen the work is bound to

think afterwards about many questions

which concern him personally. Everyone

sees himself in a giant mirror and

feels that he is addressed quite

personally. And he may come out ofthe

play a changed man. To that extent it

must at first have shocked the

audience. That also explains the

trequent remarks that

this work has wonderful music, but...

A bad

libretto.

Really, that cannot be called a bad

libretto!

But it has been

said so often that this "masquerade”

that no one could believe in...

Whether the masquerade

is credible or not is not the question

at all. If one gets

involved with this work, one has to

accept the premise that Guilelmo and

Ferrando must remain unrecognized.

They don't have to stick on lots of

beard, they simply are not recognized.

We do not have to

make it either probable or improbable.

What is new

in this score in comparison with "Don

Giovanni", in the orchestration, in

the treatment of the instruments? Is it the

trumpets, which are used more

extensively?

Only the details are new. I

would not like to claim that one hears

anything completely novel from a

technico-instrumental or musical point

of view; the whole concept is new. It

is an entirely new form of

opera in its portrayal of

the changing relationships

between six people. I can only state

that each of the three Da Ponte operas

has its own sound. There is a “Figaro”

sound, a “Don Giovanni" sound and a

"Così fan tutte”

sound, and each opera spans the gamut

of emotions from the simplest and most

intimate to the most dramatic and

savage. This range is exploited to the

full, and yet one can

say: this particular number only fits

into this particular opera.

You once told me that the spelling

of the Name "Guglielmo” is wrong.

It is simply a

modernisation of the name. Da Ponte

wrote “GuiIelmo”, the old italian form

of William which Da Ponte and Mozart

gave him, so let us not modernise him

to “Guglielmo”. Da Ponte wrote in an

italian dialect originating in Friuli,

where he came from. Hence also the

many plays on words and puns in “Così”,

the double entendres which cannot be

translated and which are better not

translated because some are very

obscene. - We have used all the plays

on words which are in the original.

For example, we did not correct

“Astrolicarti” to “Astrologarti”,

because we know that Mozart thoroughly

enjoyed these little jokes.

Astrolicarti is quite meaningless, it

is cobbled together from astrology and

“carta” (chart) to

denote palmistry...

Questions of casting

“Così” is essentially an ensemble

opera and its real protagonist is

not an individual but o sextet. I

believe that it is very important,

particularly in a recording of "Così", that the

same cast has also performed it on

the stage, that the singers have

worked together on these roles.

Yes, the temperaments and the vocal

peculiarities must be matched in such

a way that each solo and each ensemble

is naturally relevant to the relations

between the characters.

I believe it is very difficult to

produce an opera of this kind in the

studio alone. The relationships must

actually be tested. One must feel the

many-sidedness of each

utterance. The characters in “Così”

are ambiguous. They are not A or B,

yes or no, buf always everything at

the same time. But that must be tested

on the stage, the various possible

reactions must have been experienced.

Our recording is based on a staged

production in Amsterdam.

In your

recording you rather surprisingly

cast Thomas Hampson as

Don Alfonso. Normally one would have

expected an older singer and a lower

baritone for this wordly-wise vecchio

filosofo.

I was most anxious to cast the

baritone and bass parts in such a way

that Don Alfonso was a high baritone

and Guilelmo a dark

one. That is quite obvious from the

score. All the low passages are sung

by Guilelmo and he always has the

bottom line in the ensembles. There

are passages, for example in the Trio

"Soave sia il vento”, where Don

Alfonso has to sing with a delicate

mezza voce. The general idea nowadays

is: the older the person, the lower

the voice. Therefore a low voice is

used for Don Alfonso. But in the

ensembles they often change places.

Only in those passages where Don

Alfonso has to sing his own part

because Guilelmo and Ferrando have

already gone away, he has got to sing

the high notes and

has a hard time of it... Mozart gave

Don Alfonso the higher part; in Mozart

older men have higher voices. Figaro,

Leporello and Guilelmo have one type

of voice and the Count, Don Giovanni

and Alfonso have another

type of voice. Unfortunately the title

part in “Don Giovanni” is also

frequently taken by a bass, which does

not correspond to Mozart's

intentions.

The “Mozart Style”

Finally I

would like to revert to the matter with which

our interview began. This year in

particular

there is

much talk of the "Mozart Style". How

would you define the Mozart Style?

I believe that it is truly incapable

of definition. Mozart

was stylistically no

different from his contemporaries. He

employed the musical language of his

period. He just did

everything a little bit better. He

wrote in the same style as Haydn, he

wrote like Dittersdort or Salieri. In

many specific points other composers

were much more "avant-garde”

than Mozart. Salieri

wrote pieces, phrases and groups of

bars which point the way to the young

Verdi; in terms of bel

canto and in their orchestration they

are forty years ahead of their time. In

Haydn there are truly bold touches

which point the way well into the 19th

century. In purely

technical and stylistic terms Mozart

was like Bach; he did not depart from

the musical idiom of his time.

In the emotional

field, on the other hand, he went far

beyond it. Where he depicts emotions,

the breadth and depth of experience,

from the simplest to the most

profound, no one

can touch him. That, in my opinion,

constitutes the timelessness of Mozart.

It is quite

extraordinary that Mozart's

music never dates. I do not believe

there is any other composer to whom

each generation so clearly finds a

direct approach. One gets the

impression that Mozart is still alive

and has something to say to us in our

own language. Perhaps the reason is

that he is not so stylistically set in

his ways. He always does what we least

expect. Whenever we think of him as

being particularly bold, then he is

not bold at all, or only in minute

passages. He never does too much and

he never does too little. I

believe that he is such an

unfathomable figure, such an

unfathomable gift from God that he

defies analysis. We have no yardstick

with which to measure his genius.

A

conversation between

Nikolaus Harnoncourt and

Anca-Monica Pandelea

Translation: Lindsay

Craig

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|