|

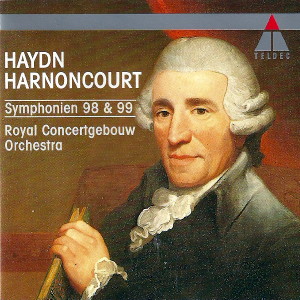

1 CD -

2292-46331-2 - (p) 1990

|

|

| Franz Joseph

Haydn (1732-1809) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie Nr. 98 B-dur, Hob.

I/98 "4. Londoner" |

|

28' 12" |

|

| - Adagio - Allegro |

8' 11" |

|

1

|

- Adagio

cantabile

|

6' 55" |

|

2

|

- Menuetto - Trio

|

4' 33" |

|

3

|

| - Finale: Presto |

8' 33" |

|

4

|

| Symphonie

Nr. 99 Es-dur, Hob. I/99 "10. Londoner"

|

|

27' 43" |

|

- Adagio - Vivace assai

|

8' 49" |

|

5

|

| - Adagio |

9' 59" |

|

6

|

| - Menuet: Allegretto - Trio |

4' 34" |

|

7

|

- Finale : Vivace

|

4' 21" |

|

8

|

|

|

|

|

| ROYAL CONCERTGEBOUW

ORCHESTRA AMSTERDAM |

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt, Dirigent |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Concertgebouw,

Amsterdam (Olanda) - febbraio 1990 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| studio |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Helmut A. Mühle / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

- 2292-46331-2 - (1 cd) - 56' 12" - (p)

1990 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

Haydn’s symphony no.

98 is the last but

one of the series of six that he wrote

during his first stay in London

for the concerts put on by Johann

Peter Salomon in the Hanover Square

Rooms. (Symphonies nos. 93-98 no. 97

was composed and performed shortly

after no. 98.) The first performance,

directed from the

fortepiano by Haydn himself, was given

on 2nd March 1792,

and, like almost all the composer's

appearances during both his visits to

London, was a great success. On this

occasion, Haydn noted in his diary

that the first and fourth movements

had to be encored. The orchestra

engaged for the Salomon concerts was a

big one (as we know from an anonymous

account in The “Berlinische

rnusikalische Zeitung” in 1794),

albeit nowhere near as large as the ad

hoc orchestras that Haydn used to

introduce his London symphonies in Vienna.

"The best orchestra in London

is the one put together

by the

entrepreneur Salomon and thus known as

the Salomon Orchestra. It

consists of 12 to 16 violins, 4

violas, 5 violoncelli, 4

double-bass, flutes, oboes, bassoons,

horns, trumpets and Timpani - some forty

musicians in all... In

each concert, two or sometimes even

three Haydn symphonies are played.

Madame Mara sings two arias, Signor

Bruni likewise... and Viotti or

Salomon plays a violin concerto. In

addition, a concerto on the

hautbois, the

flute, the harp or the

violoncello, a concerto grosso or a

quartet is usually played as well. The

whole concert is divided into two

parts, beginning at 8 in the

evening and lasting until 11 or 11.30."

As is evident from this account, the

audience was offered a fair evening's

entertainment for its money, but the

works of Haydn - symphonies and string

quartets - always formed the main

attraction, and these concerts made

him conclusively the greatest and most

celebrated composer of

the age.

The SYMPHONY IN B FLAT opens (like all

the London symphonies

apart from no. 95) with a slow

introduction which acts as a prelude

to the work's basic key, and leads up

here thematically as

well to the allegro

that follows; a solemn, serious motif

like a signal in character. Instead

of a second subject, we are offered a

variant of the theme in F major; not

until the very end of the exposition

does a chromatic oboe motif provide a

thematic contrast. As a consequence of

this exposition, the development

section is entirely dominated by the

elements of the main subject and by

contrapuntal techniques,

and the reprise

starts to go its own way, close to the

development again, after only twenty

bars: in the process, the oboe motif

from the end of the exposition is

expanded in greater detail.

The ambivalent mood of the first

movement, which wavers between

contrapuntal gravity and orchestral

baisterousness, is taken up and

reinforced in the F major adagio The

theme, which is oddly reminiscent of

“God save the King” at the beginning,

undergoes an almost complete change of

character when it returns, as a result

of darker chromaticisms and

counter-parts. The ambivalent mood is

then maintained in the minuet,

too, in surprising harmonic turns of

phrase and contrapuntal, chromatic

counter-parts which modify the

dance-like mood that is really quite

close to falk music at

the outset. We have to wait till the

finale for the tension to be resolved

by the dance-like 5/8

time and the dance and signal motifs

that are played out quite drastically

at the beginning; the soloistic,

concertante treatment of the woodwind

also plays a role. Haydn leaves us

with two little jokes: the development

section begins in the unexpected key

of A tial major with a parodistic,

leisurely violin solo (for Salomon),

while a little fortepiano solo is

built into the coda, and

this was played at the first

performance - to the astonishment and

doubtless the delight of the audience

- by Haydn himself.

The SYMPHONY IN E FLAT is the first at

the set of six written by Haydn for

his second visit to England, and the

only one not to be composed in London,

but in Vienna or Eisenstadt prior to

Haydn's departure. (Beethoven, who was

Haydn's pupil at the time,

copied out a contrapuntal passage from

the finale for himself.) Symphony no.

99 was given its first performance in

the opening concert of the 1794 season

- on 10th February, once again in the

Hanover Square Rooms. In

addition to the Haydn symphony, the

programme also featured a symphony by

Rosetti, a new piano concerto by Jan

Ladislav Dussek and a new violin

concerto by Viotti. The newspaper “The

Sun” called Haydn's work "a

Composition of the

most exauisite kind, rich, fanciful,

bold and impressive". In

comparison with no. 98, the Symphony

no. 99 seems simpler and more friendly

in disposition; the traditionally

brilliant, festive

character of the key of E tlat is most

in evidence in the opening movement. Here,

the slow introduction does not lead up

thematically to the allegro,

but is a rnotivically

independent opening, full of

tonal and harmonic tension. This

tension is then resolved in a playful

main subject which is soon enriched by

march sounds likewise typical of E

flat major. Right at the end of

the exposition, a second subject is

brought in, which is not a motif as in

no 98, but a fully-developed thematic

period that contrasts with the main

subject. Both the development and the

reprise are evolved from these two

subjects and their contrasts, in dense

and almost constant thematic work.

Considerably more serious than this

vivace is the G major adagio, whose

woodwind writing in particular makes

it one of the great examples of

the late Haydn's talent for

orchestration. The minuet returns to

the basic key and thus to the lighter

mood and the simple form

ot the first movement; only in the

trio does Haydn toy with surprisingly

assymmetrical periodics. The finale

is a sonata rondo, rather than a

sonata movement as such, as in no. 98.

Here the exuberance of the first

movement is intensified into

turbulence typical of the finale in

general; this, at the same

time, is modified by little “jokes” of

instrumentation which bring in the

tonal magic of the

slow movement, and by counterpoint

nothing short of

breathtaking. This latter element has

quite a different function from in the

symphony no. 98.: here, it does not

signal earnest gravity, but extreme

high spirits,; and, once again a

complete contrast to no. 98, such

counterpoint only occurs here in the

finale, and nowhere else in the whole

symphony.

Ludwig

Finscher

Translation: Clive R. Williams

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|